- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

John Kinsella tends to be a polarising figure, but his work has won many admirers both in Australia and across the world, and I find myself among these. The main knocks on Kinsella are that he writes too much, that what he does write is sprawling and ungainly, and that he tends to editorialise and evangelise. One might concede all of these criticisms, but then still be faced with what by any estimation is a remarkable body of work, one that is dazzling both in its extent and its amplitude, in the boldness of its conceptions and in the lyrical complexity of its moments. An element that tends to be overlooked in Kinsella, both as a writer and as a public figure, is his compassion. What it means to be compassionate, rather than simply passionate, is a question that underpins Kinsella’s memoir Displaced: A rural life.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

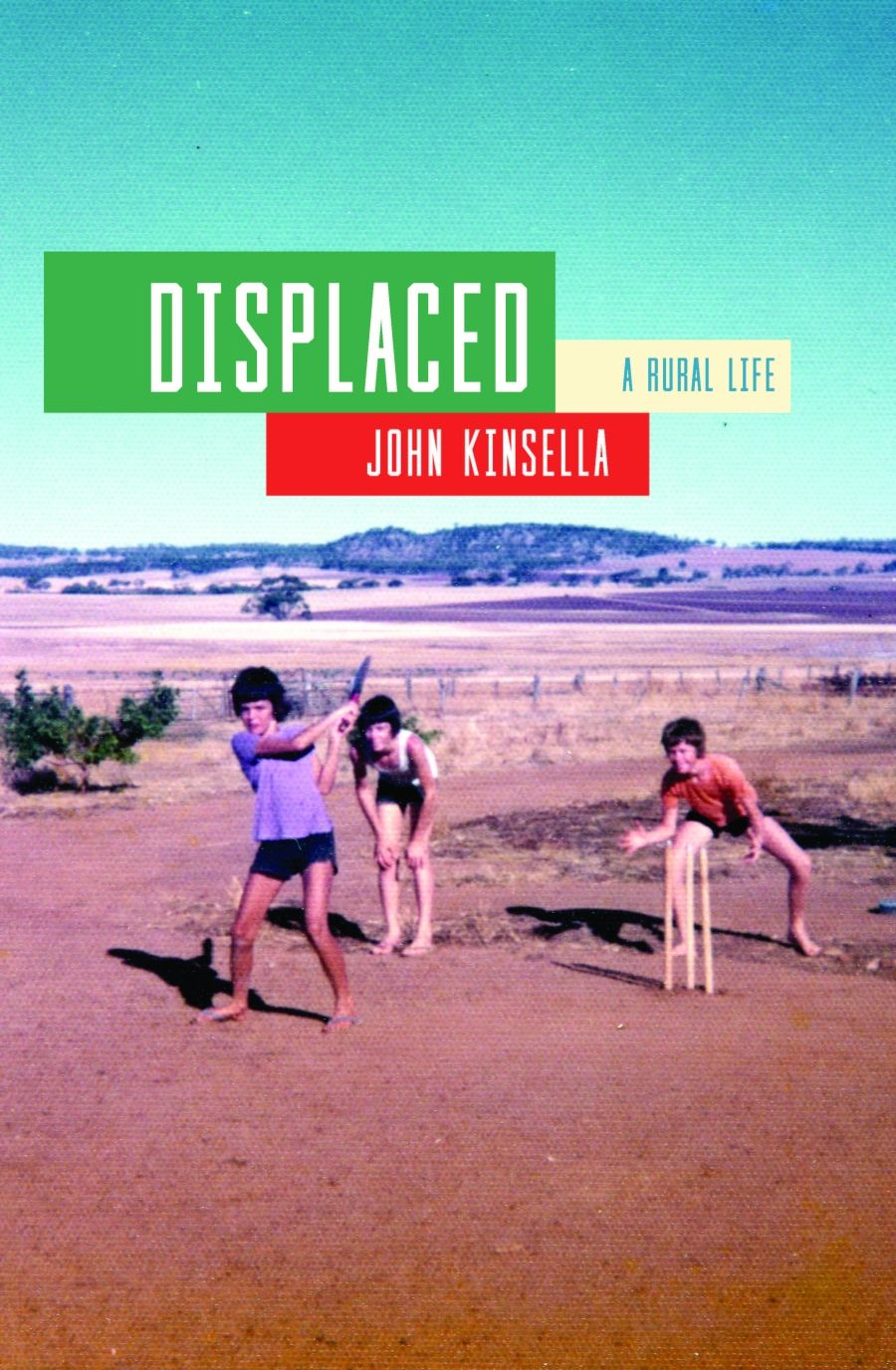

- Book 1 Title: Displaced

- Book 1 Subtitle: A rural life

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $29.99 pb, 329 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/3nDad

Displaced is the third memoir that Kinsella has written, following Auto (2001) and Fast, Loose Beginnings (2006). The gap since the previous memoir is substantial in Kinsella years, during which volumes of work come out sometimes on a monthly basis. Kinsella is now in his late fifties, and the latest memoir is powered by deeper wheels of rumination than his earlier autobiographical writings. What stands out in this new work is the candour and clarity with which he speaks about his troubled early years, years which were marked by addiction and personal torment. He has touched upon his addictions before, so this is not a revelation particular to this memoir, but in this work there is a steadier view of the person he was and the person he now is. He sources his difficulties in life to the social vicissitudes of his childhood, where he experienced repeated and vicious bullying: ‘When you’re ostracised as a child, you don’t align with the social group that expects you to be part of it. I did not belong with other kids – I didn’t belong anywhere.’

John Kinsella (photograph via Fremantle Press)

John Kinsella (photograph via Fremantle Press)

The book itself is jagged in ways that might offend certain readers seeking quietist consolations. Kinsella is neither Wendell Berry nor Annie Dillard. The tone of this memoir varies considerably, the narrative skips from place to place and time to time, and various documents are interpolated holus-bolus, including earlier poems and emails from his partner, Tracy Ryan. Yet, somehow I found myself captivated by this kaleidoscopic world. Once you surrender to its demands, the book has its own associative logic and elegance. The idea of displacement is foundational to the mode of thought the book enacts, where Kinsella feels a powerful connection to places but a powerful inhibition about belonging to them. This is the key antinomy the book wrestles with: ‘I feel a connection though I know I unbelong.’ The wanderings through time and space are linked to the purgatory of his addiction years, which he now understands as a process of desperate undoing: ‘I wandered, displaced as an addict, as someone trying to undo my own identity.’ The wandering through the rural nodes of the south-west, particularly the wheatbelt of Western Australia, is powered by addictions, which in turn drive the wandering: ‘Alcoholism and rural labouring became a strange kind of synthesis for me. From the age of twenty till thirty, I wandered, working to pay for booze and for a place to crash out.’There is a distinctly penitential quality in Kinsella’s memoir, but I admired the way that this was turned from feelings of self-recrimination into acts of reparation. The book is in many ways a love song to the home that he and Ryan have made in the hills outside Toodyay in the Ballardong Noongar country of the greater Avon Valley, an hour or so from Perth. The place where they live, which they have dubbed Jam Tree Gully, is both a home and an ethical project: ‘For me, Jam Tree Gully is the off-centre out of which I write uneasily – a point in my conception of being, almost lost but constantly rewarded (which I probably don’t deserve) by healing of the natural world against the odds, the battering ram of “progress” around us here.’ One of the agonising things about reading this book is the extent to which Kinsella still finds a part of himself unforgivable. Indeed, it is this reconciliation with himself that has been the biggest challenge to his compassion.

Being in the world, for Kinsella as for everyone, is about living with contradictions, and Jam Tree Gully offers them up without much apology. The land is bleeding with the depredations of past and present agricultural demands, and to repair the land requires intervention. But which interventions will not make matters worse, and how can these be something other than mere gesture? Who is qualified to make judgements about acts in the natural world? What is an act, after all, in the eyes of nature? Does an animal act? Does a plant? These kinds of questions, which run through and beneath Kinsella’s reveries, sketch out the broader eco ethical terrain of this memoir. In a similar vein, the book is quite clear that the land at Jam Tree Gully is the land of the Ballardong Noongar people. The narrative loops back through his own ancestors and the conversion of his Irish forebears from the abject colonised to ruthless colonisers.

I caught up with John recently on the banks of the Avon in Northam. His trademark shock of silvery hair had grown a little wild during the lockdown, yet he seemed in good spirits and was glad for some company, an emissary from the world below. He confessed he was feeling a little stir-crazy. His lines of flight, to Cambridge, to Ireland, have been closed down by the pandemic, but he was not taking it as hard as I had feared. There seems to have been, in more recent years, a hard-won process of adjustment in both him and his writing. With Displaced, Kinsella lets us in more fully to the contradictions and compassion that define one of the nation’s most significant living writers.

Comments powered by CComment