- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Language

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the early nineteenth century, Sequoyah, a Cherokee man living in Alabama, developed a fundamentally new system of writing Cherokee, which had until then not been a written language. Sequoyah’s system – properly a syllabary rather than an alphabet, in that it represents the eighty-five syllables used in Cherokee – is fascinating, innovative, and remains in use today. But in what order did those fabulous syllables go? Sequoyah provided a chart, but the missionary Samuel Worcester quickly rearranged it to suit English alphabetic order. Language was power, and ‘alphabetic order’ proved not to be neutral.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

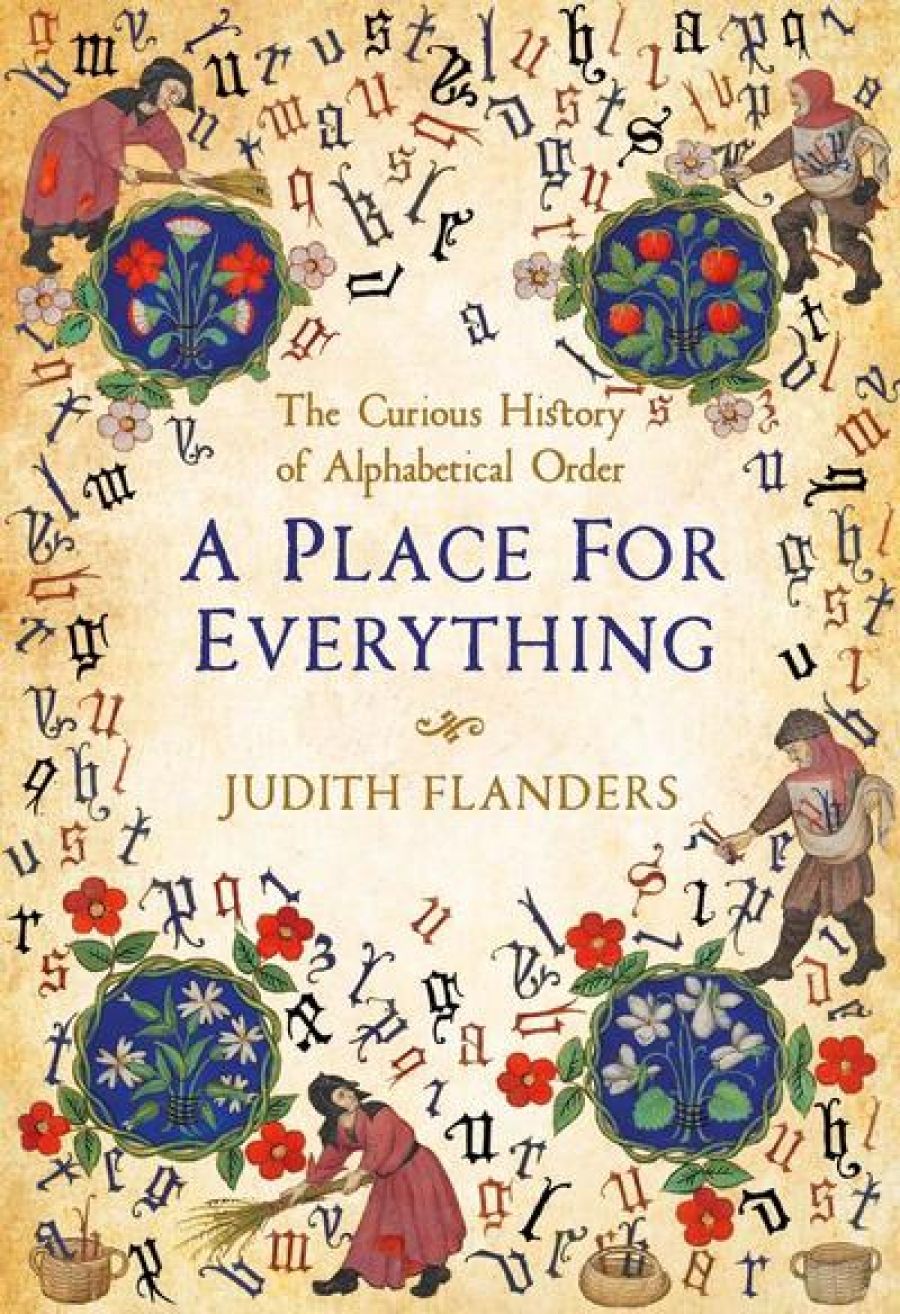

- Book 1 Title: A Place for Everything

- Book 1 Subtitle: The curious history of alphabetical order

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador $34.99 hb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/gjZe9

This book is, in large part, the engaging story of northern and Western Europe coming to embrace a new organisation – alphabetic order, commonplace books, and card catalogues – in the Enlightenment. The treatises they wrote, the furniture they designed to accommodate their ideas, and the libraries they arranged are all covered in loving detail. What receives less comment, however, are the assumptions underlying the operation. It is a whiggish sort of history: alphabetic order is ‘truly modern’, and the movement of ‘civilization’ (viz., librarians, scientists, and cabinetmakers) towards achievement is a one-way climb. These are the ideas lurking beneath this work, but they require engagement and critique.

Judith Flanders explores the development and dominance of alphabetic order in Western Europe and the United States from the medieval period to the twenty-first century.

Flanders’ style comes laden with examples, and the reader will want to know even more, not least about the Latin alphabet itself, which underpins the work, and its tumultuous convulsions. Alphabets are, after all, a tricky business. The Latin alphabet, which we Anglophones purport to use, is not quite our own. As Indiana Jones demonstrates, I and J were once interchangeable, as were U and V. W, meanwhile, is a hideously modern innovation. Other letters, like thorn (þ) or yogh (ȝ) were our own only for a time. And how should one cram the kindly yogh into alphabetic order? And what of cases like the Dutch ij, which may or may not even be a letter (depending on whom you ask), or the Roman emperor Claudius, who invented three extra, short-lived letters?

It may be clear by now that I have some reservations. Part of this has to do with the narrative Flanders presents. By training and inclination, I study the ancient world, and so am better placed to judge Flanders’ work by its details, rather than its discussions of Enlightenment encyclopedism. Now, those who set out to write a history across centuries or millennia expose themselves to a particular peril. After the author has set their narrative in place, the specialists come loping over from their disciplinary lairs to snipe and nitpick over minutiae. This is certainly possible with Flanders’ effort – the references to Egyptian ‘hieroglyphics’, for instance. Beneath that, though, a more serious issue lurks and merits attention. A quick survey of the problem will have to suffice – the use of alphabetic order for administration is known in Greek from the second century BCE, where it is attested on a papyrus from Egypt. But what put the idea in the head of that anonymous Ptolemaic official? It is likely that he got it from the Egyptians themselves, who had already developed and put into use an alphabetic order for their language before Alexander the Great arrived in Egypt. In other words, this intellectual breakthrough, which Flanders presents as essentially medieval or even early modern, and rigorously European, may well have been taught to the Greeks by Egyptian priests. All this for a people whom Flanders assures us had ‘no possibility, or need, to learn an alphabet in any order’.

It is 2020, and it should no longer surprise us that certain ideas attributed to Europeans may have originated elsewhere, as Joseph Needham’s work on China has amply demonstrated. Alphabetic order was in use in Africa and likely spread thence across the Mediterranean to Europe. This means that the smooth ascent of the alphabet charted by Flanders must be roughened considerably. Many of the conditions she suggests as critical to the triumph of the alphabet in the early modern period were present in antiquity: mass availability of relatively cheap writing material (papyri), full-word alphabetisation (not just first-letter), and even the awareness that words could be separated into their component letters. Flanders’ suggestion seems to be that medieval scholars first unlinked the letters of a word from the meaning of its name (deus, ‘god’, being composed of the letters d-e-u-s, for instance, and not simply a divine whole). The use of alphabetisation therefore would represent a smashing of social and religious hierarchies which put gods and kings before the plucky aardvark. But what if Egyptians and Romans got there first? One can scarcely imagine a more hierarchical society than ancient Egypt, where the pyramids were not just social.

Even if I disagree with the interpretation, it remains the case that Flanders tells an interesting story, and marshals a vast cast of characters to do so. For those interested in language or the history of ideas, this work will set the mind racing. That the reader’s thoughts will likely outrun the book itself may not be surprising. Every place and time has its own relationship with the alphabet, as the Jackson 5 can attest. After all, we can thank ‘Afferbeck Lauder’ for discovering the Strine spoken on these shores. Whether Cherokee or Strine, writing shapes us.

Comments powered by CComment