- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Ornithology

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

One of the most bizarre as well as unfortunate deaths in literary history occurred when the playwright Aeschylus was struck by a tortoise dropped on him by a bird. Bizarre, that is, if we don’t consider what the bird involved was doing, which was clever as well as practical. From the bird’s perspective, the tortoise was being dropped on a convenient stone rather than the bald head of a Greek tragedian who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

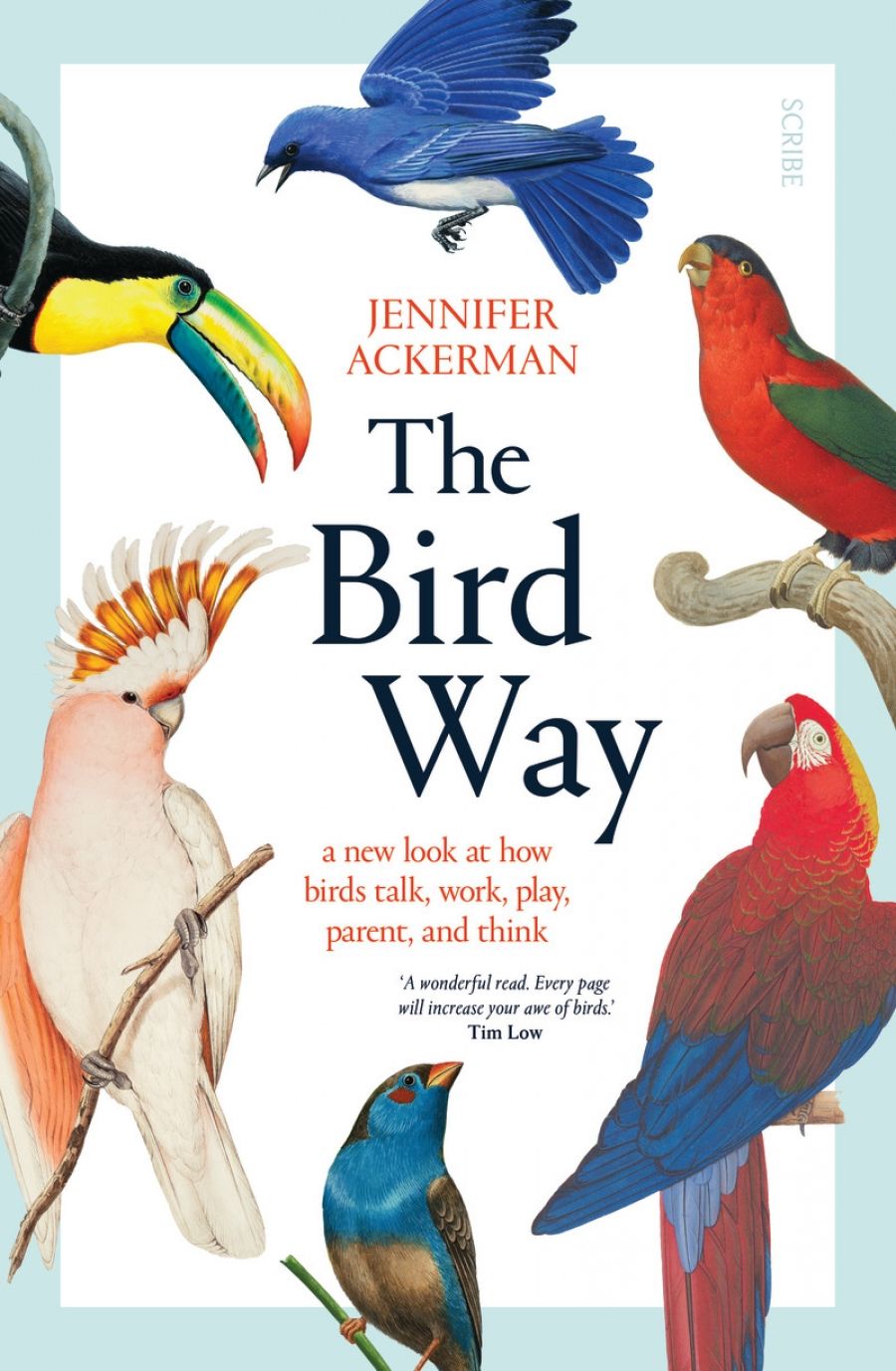

- Book 1 Title: The Bird Way

- Book 1 Subtitle: A new look at how birds talk, work, play, parent, and think

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $35 pb, 355 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/a0ygN

As The Bird Way illustrates in wonderful detail, what happened to Aeschylus nearly 2,500 years ago is but a tiny example of a world of intelligent bird behaviour, the scope and complexity of which humans are still trying to comprehend. When all the myriad species of birds are taken together, we see that they can do everything that humans can do, in addition to their ability not only to fly but to do so in complete darkness and silence. Humans did eventually work out how to fly through the air, but so far only in a mechanical way.

In recalling the demise of Aeschylus, Ackerman explains that birds, like humans and other primates, understand how to find food using gravity and other, more advanced techniques. Some birds have learned to catch fish using bait, while others have transported firesticks to ignite areas of grassland in order to flush out prey. In Australia, there are eyewitness accounts from Indigenous and non-Indigenous sources of native raptors starting spot fires by picking up and dropping smouldering sticks with remarkable precision.

Azure Kingfisher, Ceyx azureus azureus, Julatten, Queensland, Australia (photograph by JJ Harrison/Wikimedia Commons)

Azure Kingfisher, Ceyx azureus azureus, Julatten, Queensland, Australia (photograph by JJ Harrison/Wikimedia Commons)

Experiments have shown that birds can learn how to spread fire in order to hunt for food by first observing how others in the community do it. Moreover, some birds – the azure kingfisher of Australia and New Guinea is an example – watch how other animals forage for food and follow in their wake to snap up prey disturbed by non-avian counterparts. Birds can be ruthless and at times shockingly cruel – aspects of their nature also found in us.

Birds aren’t just highly observant creatures often possessing eyesight much keener than human vision; their cries and calls form a system of language as intricate as any human equivalent. Some birds, such as the lyrebird, have an astonishing capacity for mimicry of other birds’ sounds as well as the full range of noises that humans make.

‘A few birds,’ writes Ackerman, ‘even make their own tools, about as rare a behaviour as any in the animal world.’ One of the most advanced tool-making birds is the New Caledonian crow, which is ‘the only species other than humans to make and use hooked tools, little sticks with a hook on the end, which the bird uses to extract grubs and other invertebrates from tree holes and the nooks and crannies of plants’. These birds even store their tools after use.

Birds don’t always need to be taught how to solve problems – they may be able to work it out for themselves. In one well-known recent experiment, eight wild New Caledonian crows were presented with a puzzle box containing food that could only be reached if the crows worked out how to put together a compound tool by fitting together pieces of different shapes and sizes. ‘With no training or guidance’, the birds completed the task of assembling the tool within five minutes. ‘Children can’t make these sorts of multipart tools,’ notes Ackerman, ‘until at least age five.’

In addition to their impressive capacity to solve practical problems such as getting enough to eat, birds also play. Among the most playful birds are ravens and Australian magpies. The New Zealand kea has been known to disrupt human activities such as roadworks by moving traffic cones. Apparently, they enjoy messing with people’s minds and are notorious vandals.

That innate mischievousness can easily lead to trouble, just as it does for humans. The kea can sometimes be too clever for its own good, and indiscriminate slaughter by people lacking the same sense of fun has led to the species being given protected status.

Birds form relationships within and beyond their species that at the very least match what we think of as distinctly human behaviour. Sex, for example, is not simply about the biomechanics of reproduction. The rituals of certain species of birds are known to be sophisticated and elaborate. ‘The roses-and-chocolate gestures of humans can hardly hold a candle to the wild, lavish, and exuberant courtship displays of birds,’ according to Ackerman.

Some birds are functional when mating – there are examples of parents having nothing more to do with each other once fertilisation of the female has occurred. Other species of birds, meanwhile, form extraordinarily close lifelong partnerships and may even devote themselves to raising young that are not their issue. In some cases, it has been observed that gender has nothing to do with long-term same-sex relationships that arise among certain species of birds. ‘They love who they love,’ as Ackerman puts it. Just like humans.

Comments powered by CComment