- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Arnold Schoenberg and George Gershwin were two of the greatest architects of twentieth-century art music, each of them simultaneously an agent of continuity and disruption. The disruption is easy enough to chart: Schoenberg’s complete rewiring of tonality’s motherboard; Gershwin’s successful integration of jazz and symphonic music (more successful than the integration into American society of the greatest exponents of this same music). Although the continuity in each instance is slightly more nebulous, it is equally as compelling.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

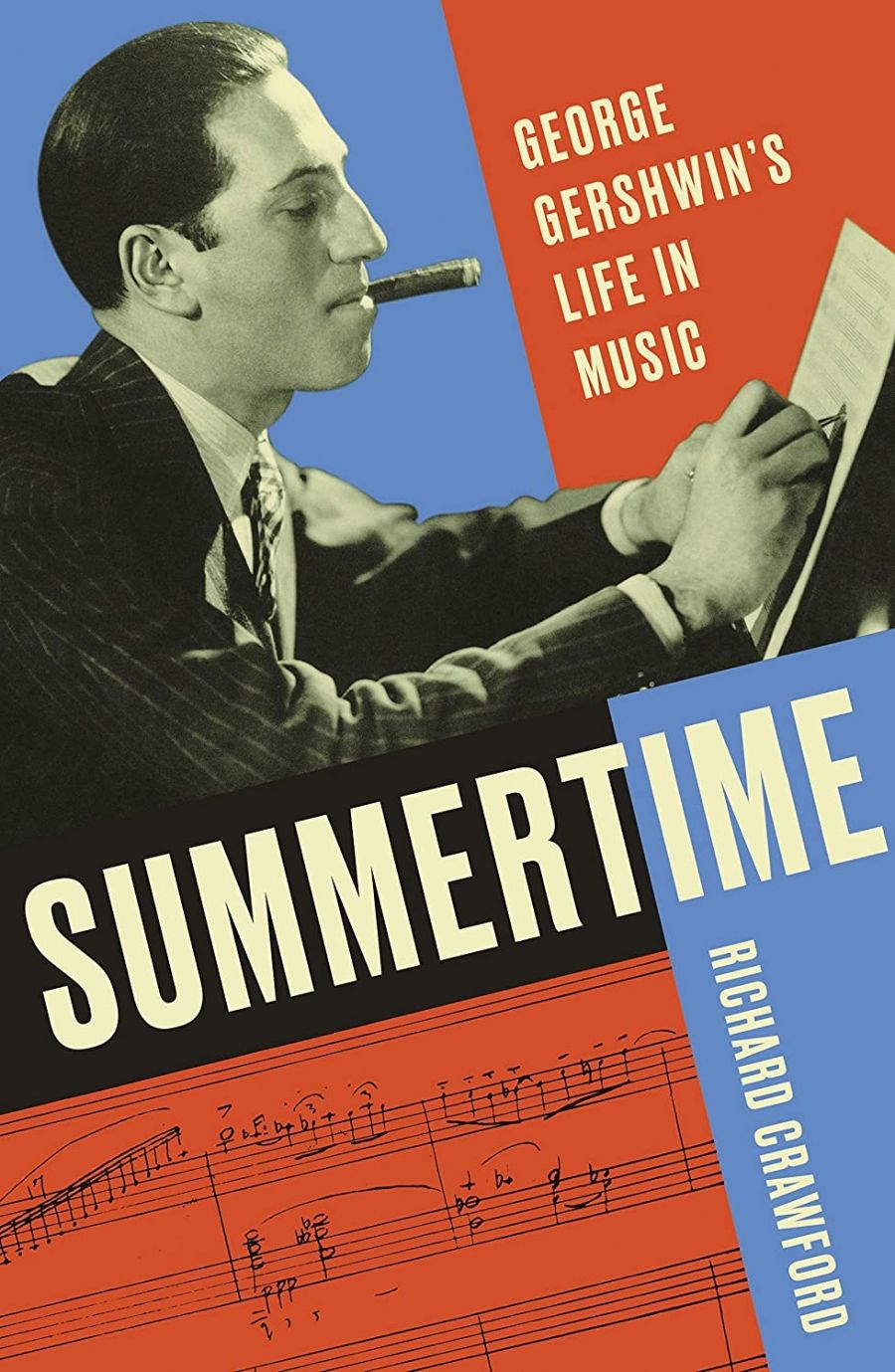

- Book 1 Title: Summertime

- Book 1 Subtitle: George Gershwin’s life in music

- Book 1 Biblio: W.W. Norton & Company, $34.95 pb, 612 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/a0yoq

George Gershwin (photograph via Ninian Reid/Flickr)

George Gershwin (photograph via Ninian Reid/Flickr)

Gershwin was both beneficiary and engineer in this regard, though in the early years he was not yet the disrupter he would become. He was the kid who studied classical piano, subsequently pimping instruments and plugging songs for one of the many American firms that in these years discovered gold in them thar hills. He did the vaudeville supper slot in the Fox City Theatre for $3.13 a night and soaked up the popular music that kept Tin Pan Alley so neatly paved. He wrote songs for musical reviews – tentatively embarking on the partnership with his brother Ira that would soon prove so fruitful – before going on to write complete shows, a number of runaway successes among them. Unusually for a composer, Gershwin was an extrovert. Ira (bookish, introvert) remembered him as a boy who lived mostly outside, his eyes blackened from fights – Italians against the Irish and both against the Jews, a rehearsal of the racial/geographic tensions in New York City in these decades that would later inspire Gershwin’s partial heir, Leonard Bernstein, when he set about updating the story of Romeo and Juliet in the 1950s.

A different personality would somehow have missed these opportunities; next to Gershwin, Cole Porter couldn’t seem more white. Gershwin’s composition teacher Edward Kilenyi identified in his gifted pupil ‘an extraordinary faculty for absorbing everything he observed and applying it to his own music in his own individual ways’. And then some! Reminiscing about his years as a song plugger, Gershwin fondly remembered the ‘coloured people [who] used to come in and get me to play “God Send You Back to Me” in seven keys’. It was an unbelievably fertile apprenticeship, but so too was Gershwin uniquely built to serve it: unending curiosity, great facility, and an absence of bigotry collided with spectacular effect.

Richard Crawford has added to the long line of biographies of this most intriguing subject, leaning heavily on his years of research into that most wondrous cauldron of American culture: the emergence of a vibrant art-music industry at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. And he does it beautifully. The pace is fast, the nuggets carefully mined, the prose unflashy but good. And he writes as a real musician, able to turn sound into words. The cast of characters is long yet perfectly disciplined. The eleven-year-old Oscar Levant pops up to describe hearing Gershwin play piano in his show Ladies First, Levant ignoring the stage to focus on the pianist who had caught his ear (‘I have never heard such fresh, brisk, unstudied, completely free and inventive playing’) – much as Anita Lasker Wallfisch, in the horror of the recently liberated Auschwitz, found herself blocking out Yehudi Menuhin’s playing so that she could concentrate on Benjamin Britten’s accompaniment. Fellow Jewish immigrant Irving Berlin turns down Gershwin as his musical amanuensis (‘What the hell do you want to work for anybody else for? Work for yourself!’), while the pianist Lester Donahue recalls that the conversation among party guests following the Carnegie Hall première of Gershwin’s Concerto in F – with the composer as soloist – was a spirited debate about whether Gershwin should abandon Broadway immediately to concentrate on orchestral music and opera.

‘I wrote this concerto in that form,’ Gershwin told a reporter during rehearsals for the première, ‘because Mr. Damrosch was interested in my Rhapsody and wanted me to write in a form that could be used by his orchestra … I got out my books and studied up on the “concerto” style and then wrote.’ This single anecdote sums up Gershwin’s genius and lack of pretension. Embarrassingly for me, the concerto is a work that somehow has never been on my radar. Last year, following a blistering performance of it by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra under David Robertson, I found myself apologising to the soloist, Kirill Gerstein, for this lacuna. He was gracious in his deflection, yet this astonishing virtuoso – who grew up playing jazz and was recently the dedicatee of a fiendishly difficult new concerto by Thomas Adès – is Gershwin’s most perfect advocate, one foot planted firmly in each world. Gershwin now has another, for Richard Crawford has written an elegant and quietly passionate book.

Comments powered by CComment