- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Art and Paris meant everything to Agnes Goodsir. ‘You must forgive my enthusiasm,’ she wrote. ‘Nothing else is of the smallest or faintest importance besides that.’ Goodsir was the Australian artist who painted the iconic portrait Girl with Cigarette, now in the Bendigo Art Gallery. It depicts a cool, sophisticated, free-spirited woman of the Parisian boulevards. When Goodsir created it, in 1925 or thereabouts, she had lived in Paris since the turn of the century. Apart from brief visits back to Australia, she stayed there until her death in 1939.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

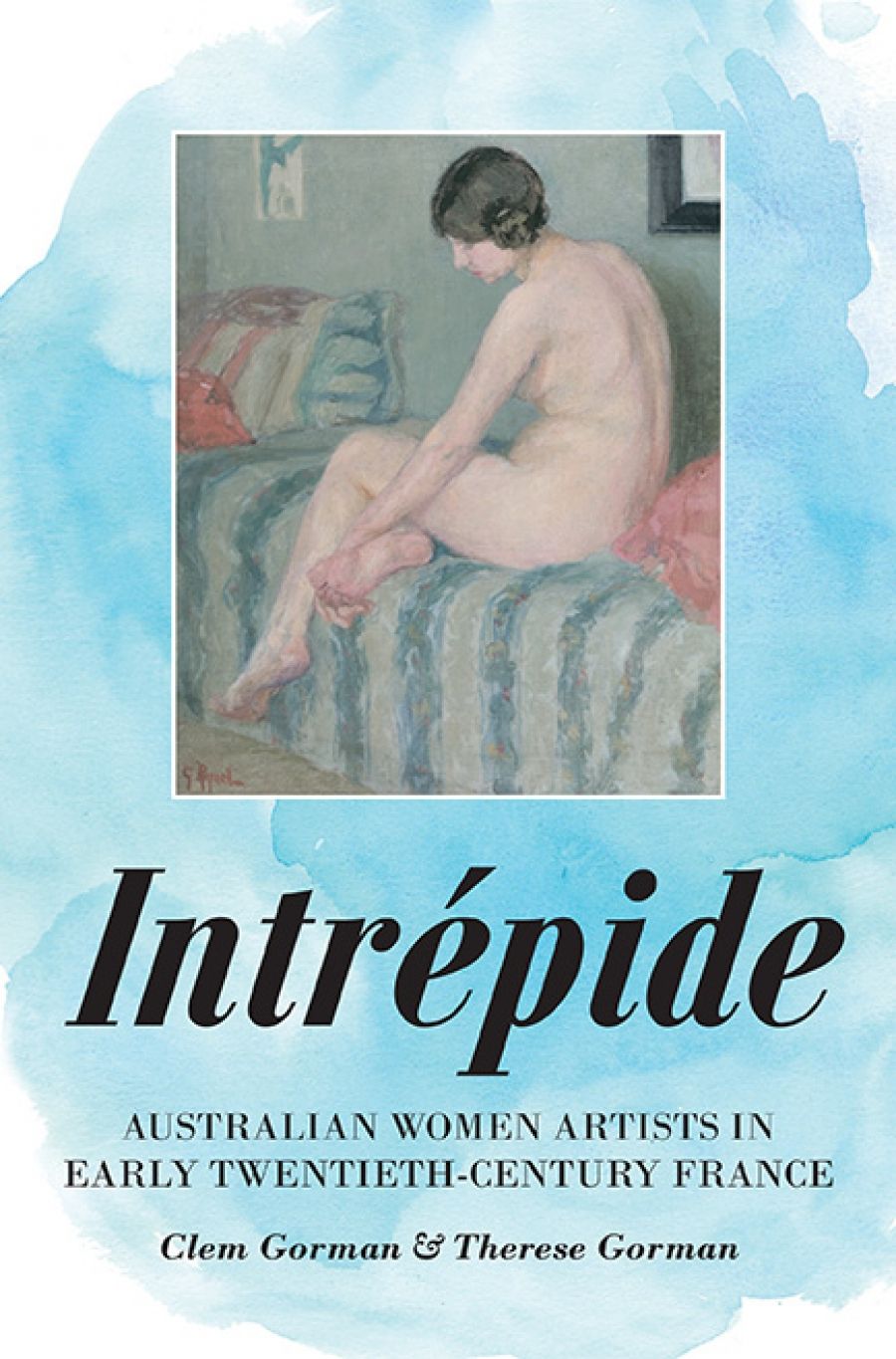

- Book 1 Title: Intrépide

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian women artists in early twentieth-century France

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $34.95 pb, 268 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/7z1Xr

The authors are a husband-and-wife team: Clem writes on the visual arts, and both are working on a biography of the Sydney artist Wendy Sharpe. The real strength of their research here is to uncover the history of many more Australian women artists working in France in the early twentieth century who are now little known, and in some cases forgotten. As the Gormans demonstrate, they deserve much wider recognition. This is a subject that resonates with me because of my own family history. Although my mother, Victoria Cowdroy, never made it to Paris, she was one of those forgotten women artists of the early twentieth century who have won belated attention from contemporary art scholars.

What were the twin attractions of art and Paris to these women, who all found this intoxicating combination every bit as important to their lives as Goodsir did? Before World War I, and then between the wars, the City of Light was the world capital of art. It had the best art schools and teachers, galleries and salons, and was the home of exciting new movements like Cubism and Modernism. An artist could rent a modest Left Bank atelier, albeit up many flights of stairs and often without running water, and pop out to the lively local cafés to network with mentors and peers, or simply to enjoy the heady bohemian atmosphere.

Margaret Cole, an English socialist politician, writer and poet, painted by Stella Bowen in 1944–45 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Margaret Cole, an English socialist politician, writer and poet, painted by Stella Bowen in 1944–45 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Anyone expecting wild tales of louche women letting down their hair and dancing on tables will be disappointed. A few did embrace the bohemian life, but they were all there to work, and they took their work very seriously. Hilda Rix Nicholas, who went to Paris with her mother and sister, was a typical ‘decent, provincial Australian’; though her art developed and blossomed, she herself stayed that way.

Male artists were drawn to Paris, too, but a female pilgrim had far more obstacles in her path, which means that she truly deserved to be called intrepid, especially when she came from half a world away and from a background that didn’t value art as a calling for women.

Money was the main obstacle. Many of these women came from wealthy families who supported them, but not all. Marie Tuck, who spent fourteen years in France, saved the money she earned from ten years of teaching art in Australia until she had enough to travel to Paris. Then she cleaned the studio of Australian expatriate artist Rupert Bunny so that she could pay him to teach her.

Anne Dangar, a disciple of the Cubist painter Albert Gleizes, slaved away in the garden of an artists’ commune to earn her keep. She had little help from her rich family. The mother of her longtime friend Grace Crowley was proud of her daughter’s art until it started to look like a profession. When young Grace took a break from art school, mamma sacked the maid, expecting her daughter to perform her household duties.

Crowley was happy in Paris and embraced Cubism. Her career was just beginning when a family illness summoned her back to Australia. The illness was nowhere near as serious as had been made out. The authors speculate that the family threatened to cut off her allowance if she didn’t return.

Most of these women were single (and some, surely, were lesbians, though we know very little about their private lives). But was it any easier for those supported by husbands? The trials of Stella Bowen with her demanding and spectacularly unfaithful husband Ford Madox Ford have been well documented elsewhere, but she wasn’t the only woman to find marriage a mixed blessing, to say the least. Devoted as she was to her husband, Eric, Constance Stokes commented: ‘Any creative work is a difficult life for a woman if she is a wife and mother.’ Both Dora Meeson and Ethel Carrick were tireless in their promotion of their husbands’ artistic careers, at the expense of their own work.

Some women’s shy and self-effacing temperaments held them back from the kind of relentless self-promotion that a successful career often demands. Even so, their achievements, whether they followed a traditional path or broke away into Modernism, were astonishing. Those who returned to Australia introduced a parochial, backward, and sometimes wowserish culture to new ideas and techniques that they promoted through exhibitions, teaching, and their own example.

Inevitably, the question will be asked: were these women at least as good as their male counterparts in Paris? The authors are in no doubt, and their crusading spirit is infectious. While it is difficult to evaluate each individual artist’s work from the small number of colour reproductions in the book, I hope this text will be the start of a wider and deeper appreciation of what these artists did, and the many obstacles they overcame.

Comments powered by CComment