- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Stranger Artist is a finely structured and beautifully written account of gallerist Tony Oliver’s immersion into the world of the Kimberley art movement at the end of the twentieth century; the close relationships he developed over the following years with painters such as Paddy Bedford, Freddie Timms, and Rusty Peters; and the creation of Jirrawun Arts as a collective to both promote and protect the artists and their work. How these artists, under Oliver’s practical guidance, came to assume the mantle of the legendary Rover Thomas and took Kimberley art to the world provides a compelling narrative: from fascination to enthralment to disillusion. Dreams are born, bear fruit, and die. Like many a fine work of art, The Stranger Artist attracts with a brilliant surface while fascinating with its deeper layers. Behind the thrill and wisdom of the painting – so new and old, so luminous and dark – lurk the tragedies of history and dysfunctional politics. This book – how could it be otherwise? – is peopled with spectacular characters, art, and landscapes. Appropriate to this remote corner of Australia, it is full of intense colour and eccentricity, while also permeated with great sadness.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

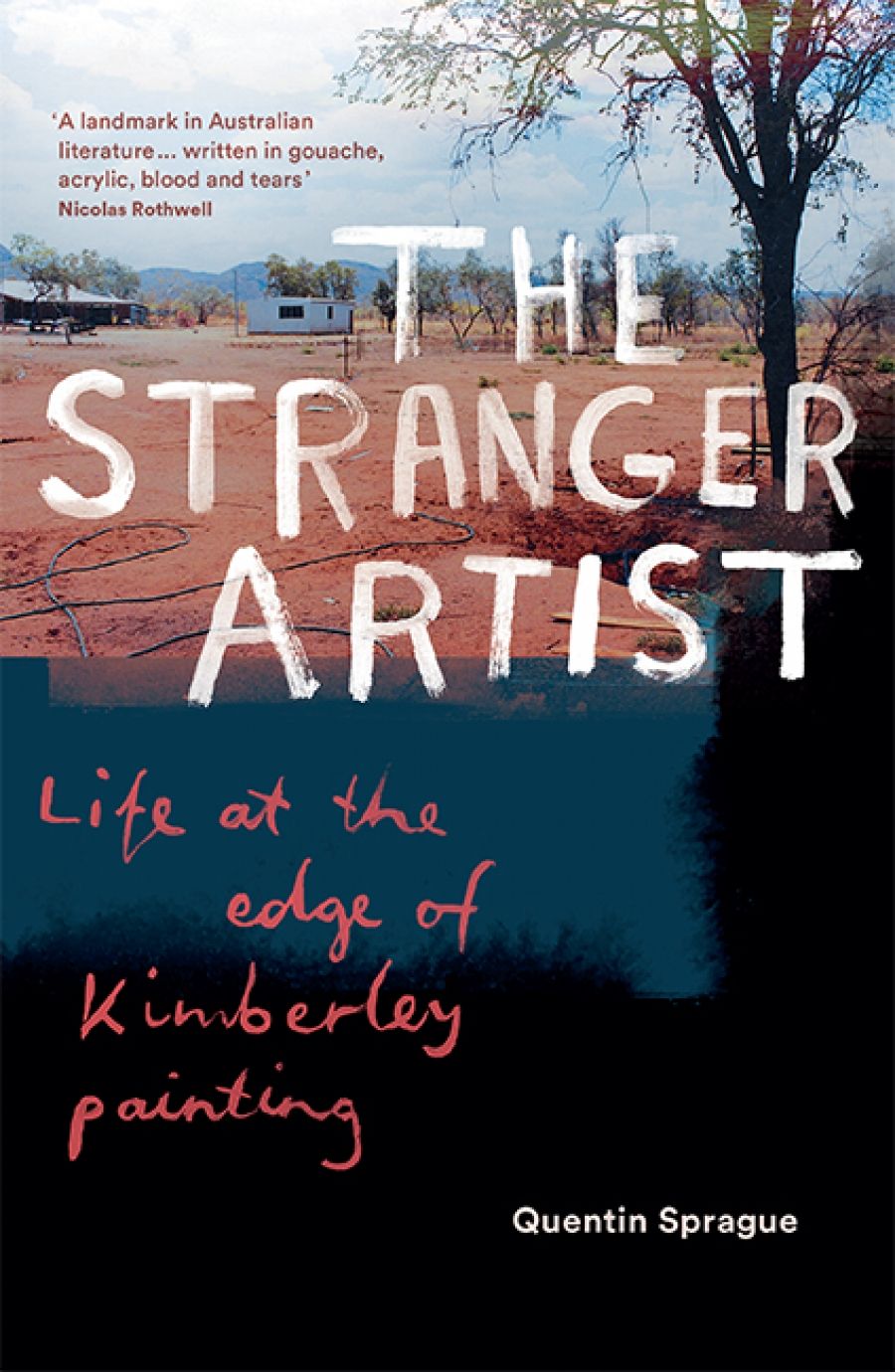

- Book 1 Title: The Stranger Artist

- Book 1 Subtitle: Life at the edge of Kimberley painting

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $32.99 pb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/N72Gv

The subterranean channels of Quentin Sprague’s narrative lead the reader to explore more profound questions about the nature of art, of its capacity to inform and perhaps heal; to consider how Indigenous expression works within white cultural frameworks, and how such expression plays out in the broader context of Australian culture and its ambitions. This is a powerful story of Indigenous art and its relationship to our often bloody history. The book also provokes questions about representations of reality – of how the Kimberley artists rendered their world, and how the driven, obsessed, and perhaps slightly mad Oliver held together his visionary project through both doubt and ecstasy. For the Indigenous artists, painting was the revelation of ceremony and Law, and their relationship to the origins and nature of the world. It was also a way of accounting for history: the largely untold story of the dispossession and massacres of the Gija people in the late nineteenth century.

Quentin Sprague (photograph via Monash University)

Quentin Sprague (photograph via Monash University)

Sprague rises to a difficult challenge: the meeting point between the English language – both generous and limiting – and the art under examination. For here are a series of translations and mutations, from the nuanced folds of the Kimberley landscape to Indigenous art, to the language of the writer, each time filtered through eyes, memory, sense, and the shifting mirrors of the human heart. Writing of Rover Thomas’s art, Sprague displays his deft rendering of potentially difficult subject matter: ‘sublime beauty … fields of open colour cut through by lines of ragged dotting; the surfaces were dusty and tactile, in themselves a gentle revelation’. The reader is in good hands.

Sprague understands, as did Oliver, that the Kimberley art movement – in its heterogeneous collective, one of the great visions splendid of recent Australian culture – emerged from a formally ruinous social space, of communities hidden away in decaying homes, too often dependent on the ‘arrogant paternalism’ of the local white population. Alcoholism and suicide deplete one Indigenous generation after another; somehow from this bleakness, teased out by Oliver’s relentless drive, comes astonishing pictorial light.

Yet even as Oliver decamps from the distractions – social and grog-related – of Kununurra and relocates the Jirrawun workshop south to Crocodile Hole, then to Bow River, back to Kununurra, and, finally, to the realisation of his gallery at Wyndham, there is a sense of collapse, despite the supreme efforts of the assorted Kimberley artists – a sense that all this could only last so long, threatened not just by ongoing structural poverty, age, and ill health, but also by greed, remote community politics (often involving white administrators), clashing personalities, the whims of fashion, and, parallel but still important, the financial malfeasance and collapse of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC). ‘[A] patchwork,’ Sprague notes, ‘of unresolved histories, a mess of competing visions calcified.’

Even when great success comes, most notably through the fame and fortune of Paddy Bedford, there is a sense that it might not be true: Bedford, Sprague notes, ‘had used paint to transcribe his Dreamings and received in exchange a thick wad of fifty-dollar notes’. Was this, in some sense, all too easy? While many marvelled at the new worlds revealed and their undeniable, even indescribable power, it was only a matter of time before the mundane but inescapable laws of commerce and productivity took over.

Sprague convincingly portrays Oliver as both observer and, at times, participant in the flowing translation of history and law into art. Unlike white painters he had known, hemmed in by anxieties of influence, worried by the anticipated public and critical response that can determine (or undermine) the very nature of a work of art, the Kimberley artists were oblivious to such concerns. Their work seemed ‘effortless: a simple combination of lines and colour and dots reworked in endless variation’. There is something to be said, in this observation, for the enduring power of tradition; for the power of belonging, and for having deep roots in the world, and drawing on the stability that provides.

It was not a stability that would protect Tony Oliver. Key artists and other figures central to one of our nation’s most important art movements began to die; Oliver ultimately seeks a form of resolution in Vietnam. Sprague had described him as operating along a ‘schizophrenic edge’, attempting to satisfy the demands of two worlds while balancing his own inner conflicts. Around him whirled the complex rivalries of the Kimberley collective, its ambivalent relation to money, fashion, and influence, all within the ongoing context of Indigenous political affirmation.

Comments powered by CComment