- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

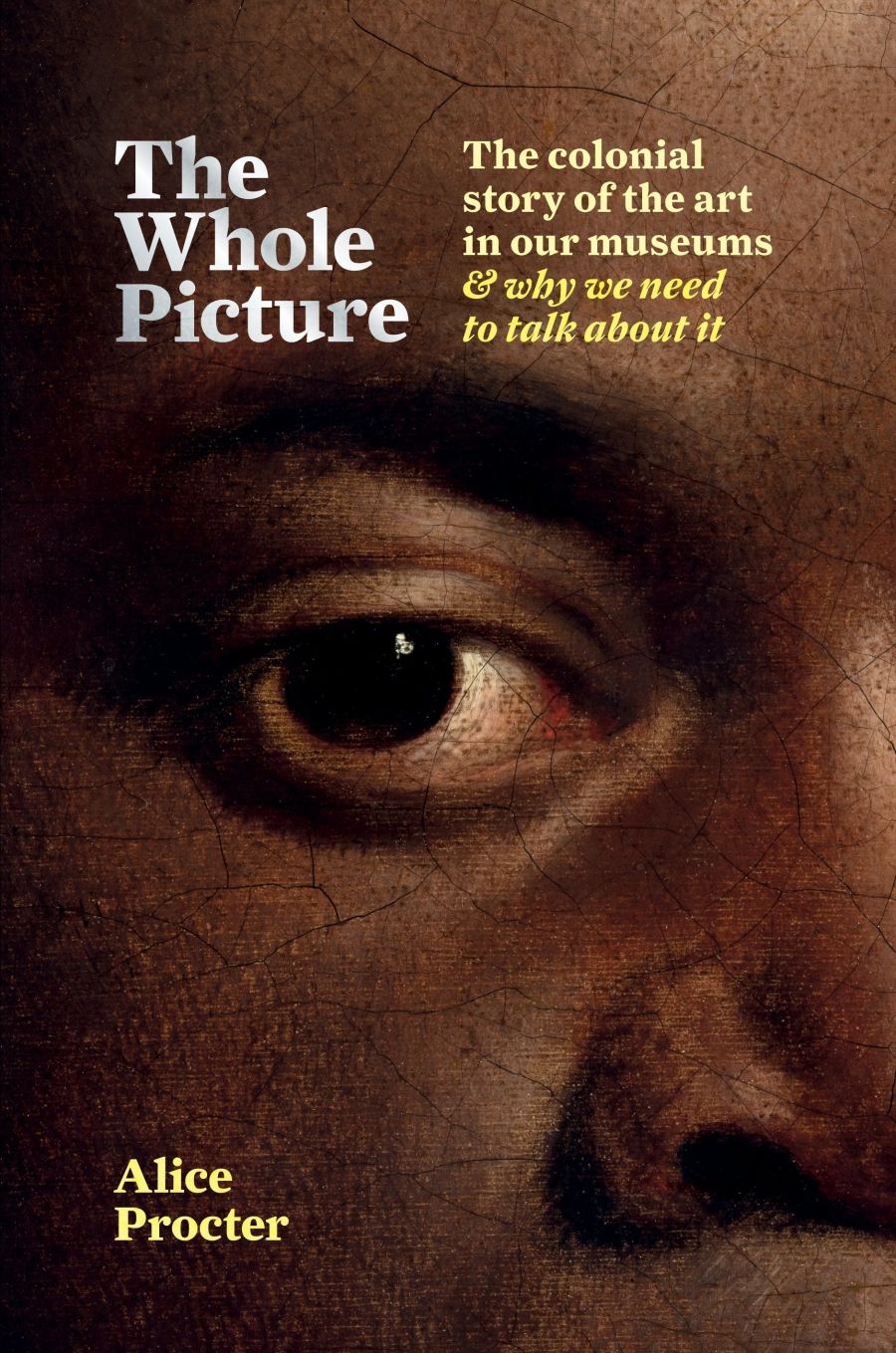

You are looking at a book. On its cover is a painting of a person of colour. But you can only see a portion of the piece. The face is obscured. One dark eye takes up the middle third of the page, while one nostril fills the bottom right-hand corner. The painting is covered in a layer of fine cracks – presumably due to its age. These lines show that myriad individual pieces make up the image before you, but this is still only one part of the picture. Frustratingly, you cannot see the face as a whole.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: The Whole Picture

- Book 1 Subtitle: The colonial story of the art in our museums and why we need to talk about it

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $39.99 hb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/vYEDO

Sitting comfortably at the nexus of postcolonial studies, art, public, imperial, and settler colonial histories, The Whole Picture is an example of interdisciplinary writing at its best. Framed as a guide to colonial museums, the book is divided into four sections to reflect four categories of museum spaces: the palace, the classroom, the memorial, and the playground. The chapters within each section unpack the history and significance of a particular object, work of art, or museum controversy. Alongside this thematic separation, the book builds chronologically, moving from the ‘great white men’ who created the first museums (as well as remarkably resilient ideas about what constitutes ‘art’), through to contemporary artistic interventions that seek to alter, critique, or hold a mirror to museums in an attempt to challenge these colonial legacies.

This book was born of Procter’s experience running ‘Uncomfortable Art Tours’ about the colonial history of art in British museums, and this inheritance clearly shows. There is a remarkable symmetry between Procter’s book and the museums and stories that she describes. In the opening to this review I have mimicked Procter’s writing style as she starts each chapter with a vivid description of you, the reader, encountering the object or work of art under discussion. The conversational style, first-person narration, and visceral descriptions make for an immersive experience. The book is designed to draw the reader in and situate them in the narrative. This not only makes for an engaging read, but makes us feel our complicity in the colonial stories that Procter is telling, as well as our power to change them.

The Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum (photograph by Michael Paraskevas/Wikimedia Commons)

The Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum (photograph by Michael Paraskevas/Wikimedia Commons)

While Procter crafts a careful and incisive argument, this point about empowerment ensures that the book does not replicate the same unequal power dynamic as the museums it critiques. The Whole Picture provides readers with not simply an alternative history but with the analytical tools and insight for them to critically engage with these stories themselves. In this way, Procter’s work reflects a shift in public history that sees historians as facilitators rather than as the sole authorities of the past. Time and time again, with historical and contemporary examples, The Whole Picture illustrates the disruptive potential of the museum visitor. Sacred objects meant to be approached with reverence can be desecrated; art designed to probe past injustice can become fodder for selfies. But equally, a work of art can be read against the institution that houses it; marginalised voices can be articulated and heard through thoughtful design and a willingness on the part of the visitor to engage.

The Whole Picture focuses on physical museums and art galleries, but its message can easily be extended to the virtual museum spaces that have proliferated since the outbreak of Covid-19. While digital galleries may appear inclusive and democratic by virtue of their accessibility, they are just as fraught as physical museums. Whether physical or digital, we need to be critical of these spaces. Procter pushes us to ask: what items do museums display, and why? Whose voices are receiving a platform, and whose voices are being silenced? Who has power over a museum’s narrative? What do they choose to say?

This book explodes the notion that we can ever access the whole picture when it comes to colonial art and museums. There is never one perspective from which to view history, just as there is never one way for a visitor to engage with art. Art and engagement are always about choices. There is nothing inherent or inevitable about them. With discernment, reflexivity, empathy, and care, Procter shows us how to access the layers of meaning that are hidden beneath museums’ claims to truth, and how to recognise our own place in these narratives. With that knowledge, we are better equipped to approach museums as sites of contestation, politics, emotion, and change. The stakes are clear. Once we know the colonial story of the art in our museums, we are no longer beholden to history; we can start changing it.

Comments powered by CComment