- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I must admit to being intrigued by any self-proclaimed ‘Histories of Everything’, so I leapt at the prospect of a dense history of my favourite creative art and how it flourished in our past centuries, right down to a couple of writers who died in 2019. And occidental only: that is, apart from a sidelong glance at Hafez, Tagore, and Li Po’s fellow poets. Unless you regard the Russians, that is – bridging East and West.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

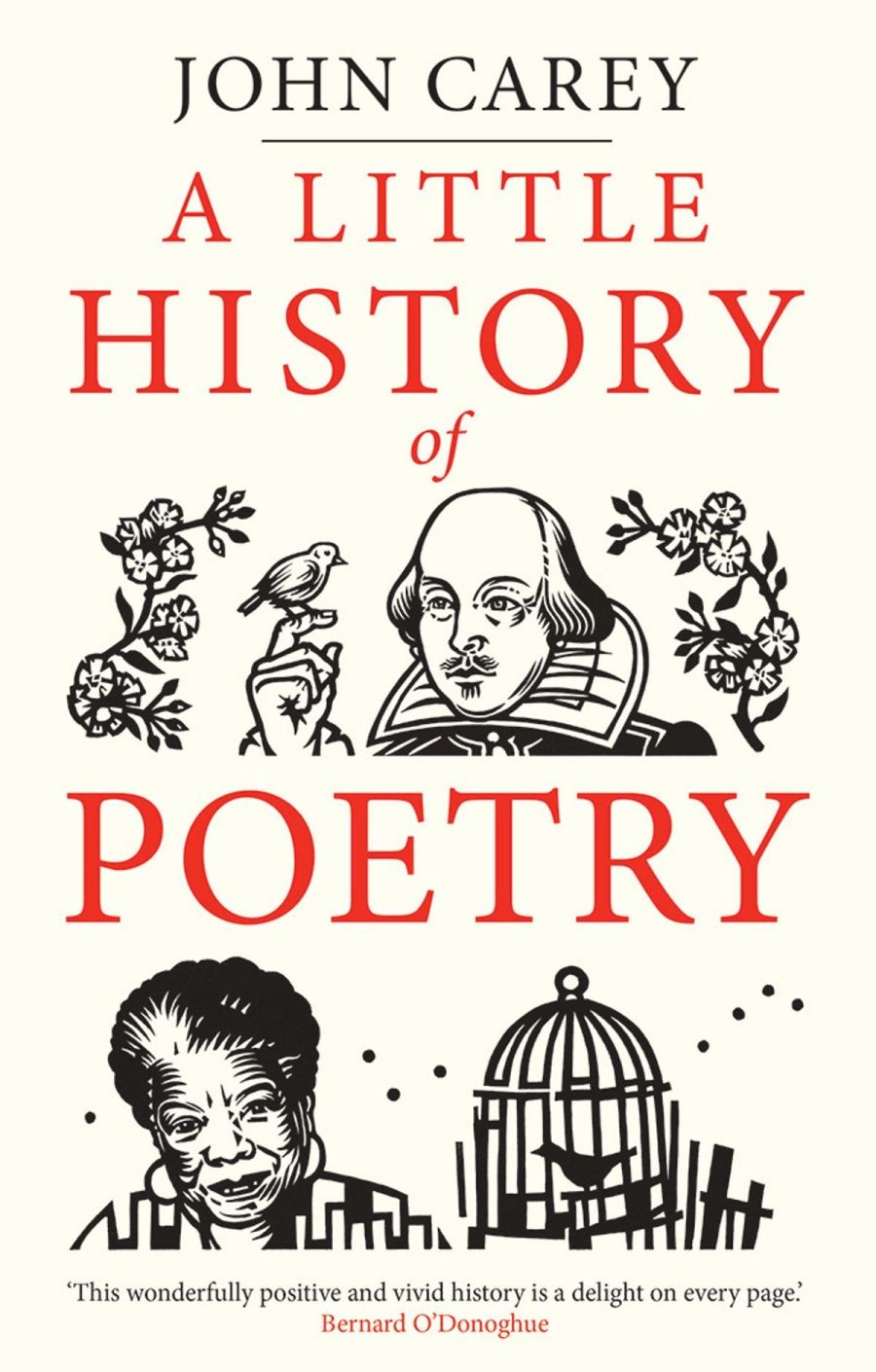

- Book 1 Title: A Little History of Poetry

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint), $43.99 hb, 312 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2ZVRg

In many cases, ‘belief had its comforting side’. As Vaughan was to write, ‘I saw Eternity the other night; / Like a great ring of pure and endless night.’ He was very lucky in that respect.

We find here that long lives come seldom into the making of great poetry, at least until recent times. More often, the pained sprinters did well. Whereas ‘Auden did not improve with time’, well, allegedly. Careful, there, dear scholar!

Carey presents us with Rilke’s reinvention of Eurydice, in the German’s lyrical assertion that ‘she too was full of her immense death / which was so new she could not take it in’. These modernist poets pounded their languages into new forms, very much as elegant Andrew Marvell had in the last season of the Renaissance, for all that he had those light-fingered quatrains, ‘annihilating all that’s made / To a green thought in a green shade’. Yes, he made all poetry greener: and kept it vegetally witty.

Oh yes, Carey is a stylish, even witty writer himself. He gets down to the nubs and gists of things, or of people, with an admirable clarity. We could say that he, too, makes everything greener or a bit more sparkling. His wit renders things clear, almost too boldly at times: he seems the genuine communicator. So readable.

Thus he writes of the medieval riddle poems, ‘They are tricky. Some remain unsolved after a thousand years.’ And of Milton’s fall of Adam, ‘Why does God let it happen? He knows everything, including the future, so why doesn’t he step in and stop it?’ Later, he reminds us that even Emily Brontë ‘has joyful poems, too’, while he rises splendidly to the steppe grandeur of Lermontov’s battle poetry. Metaphorical again, he gives us Marianne Moore like this: ‘Disguise, admired in the pangolin, was something she practised herself.’

Many of his other insights and distillations will give potential readers a kick, or even an agreeable sigh. I do like his sense that, in ‘The Faerie Queene’, Spenser invented the robot. There’s sci-fi for us all! In fact, poets were not all that good at science-fiction, preferring rural landscapes, personal heartbreak, and red wine, like Scotland’s Robbie Burns.

In particular, Carey is compelling on the dodgy, charmingly transatlantic modernist T.S. Eliot, who ‘excludes everything pretty and decorous, and his language is a rag-bag of strange words, some from dialect, some his own invention’. That’s pretty good, isn’t it? But then, this book is much like a yummy Christmas feast or a children’s party: full of delicious utterances and just quotations. It winks and invites a wary reader to enjoy the party, even if Baudelaire’s ‘self-pity can pall’ or, worse, Lewis Carroll ‘had a weakness for scantily-clad little girls’. Or of the Big Wal, ‘Many of Stevens’ poems are baffling. You cannot tell who is speaking or to whom or about what.’ But can we tell that with Pope or Pushkin, except for the fact that the latter ‘left many discarded women in his wake’?

The only Australian to get a guernsey for his poetry here is, no, not Peter Porter or Judith Wright, but Les Murray, who comes stoutly in to bat with his ‘down to earth’ values on the very last page. Alas, we seem to remain antipodeans down here. But Murray is in the sturdy, ever-eloquent company of Ireland’s Seamus Heaney. No doubt he would have been happy enough with that. As our author reflects on another recent poet, ‘Defeat is inevitable. But that does not alter the poet’s responsibility.’

There are odd occasions when a bold anthologist of poems and poets can sound a little too much like some downright ratbag journalist. Carey is not often tempted, I’m glad to say. And he keeps us reading. After all, he can write like a hypnotist – or even an inky angel. Any reader of poetry will get swags of joyous information from this book.

Comments powered by CComment