- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the end of 1910, Irving Berlin took a winter holiday in Florida. James Kaplan writes, ‘Here we must pause for a moment to consider the miracle of a twenty-two-year-old who in recent memory had sung for pennies in dives and slept in flophouses becoming a prosperous-enough business man to vacation in Palm Beach.’

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Irving Berlin

- Book 1 Subtitle: New York genius

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint), $49.99 hb, 424 pp

On the very day of his departure for Florida, before heading down to the newly opened Penn Station, he recalled a syncopated march tune he’d made up a few months earlier, and fitted some words to it. It was about a bandleader called Alexander, and it celebrated a new musical fashion. In 1911, ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’, gave Berlin his first bona-fide hit, with others quickly following. Later that year, ‘Everybody’s Doing It Now’ brought together the ragtime craze and the younger Izzy’s talent for smutty lyrics. It was also in 1911, right at the end of the year, that Berlin met and fell ‘hard’ for the nineteen-year-old Dorothy Goetz. Everything happened quickly. By February 1912 they were married, honeymooning in Havana, where Dorothy picked up typhoid. She contracted pneumonia in June and died in July. Berlin, ‘precocious in many things, including sorrow’, was now a twenty-three-year-old widower.

Alongside novelty dance numbers such as ‘I Love a Piano’ and ‘When that Midnight Choo Choo Leaves for Alabam’, Berlin now developed a line in songs of love and loss. ‘When I Lost You’ was an immediate hit, and ‘All By Myself’, ‘What’ll I Do?’, ‘All Alone’, and ‘Always’ followed over the next decade and a bit.

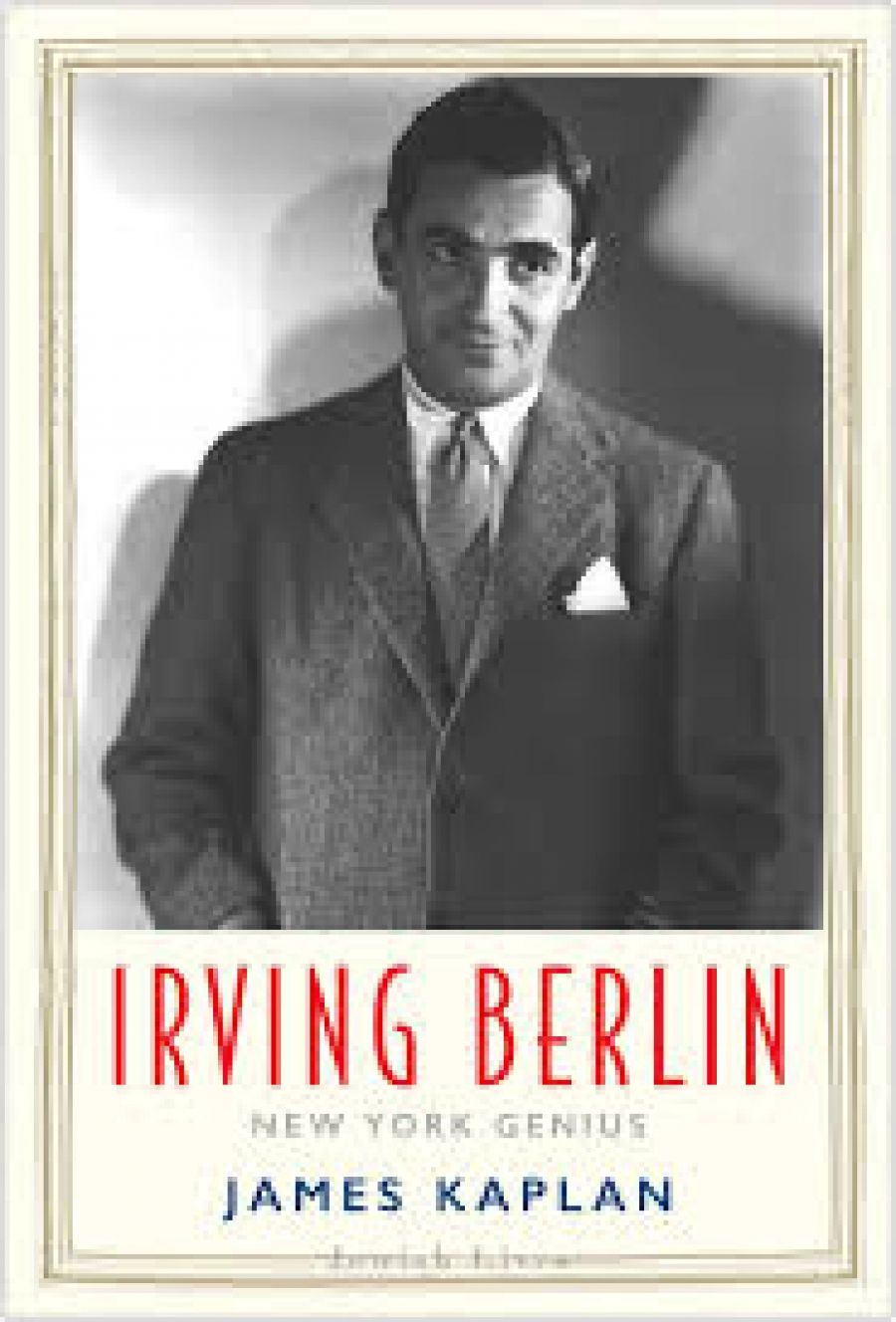

Irving Berlin (photograph via Britannica)

Irving Berlin (photograph via Britannica)

Part of Berlin’s success was his work ethic. ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’ might have been completed in a hurry – after all, he had a train to catch – but more commonly he would ‘sweat blood’ over his songs, friends claiming they always knew when he’d completed one, because he looked drawn and wan having been up all night.

The aim of this labour was simplicity of form, clarity of words, lucidity of melody. Stephen Sondheim, an admirer of Berlin, though not an uncritical one, compared him to Cole Porter (all three – Berlin, Porter, and Sondheim – wrote both words and music). ‘The seeming artlessness of [Berlin’s] music matches the seeming artlessness of the lyrics,’ Sondheim wrote, ‘just as the elegant self-consciousness of Porter’s matches the elegant self-consciousness of his. Berlin knows how to inflect words melodically and rhythmically so that they seem to flow organically; the listener is rarely aware of the songwriter.’

The artlessness that Berlin worked so hard to perfect (and that was brought to life so artlessly by favoured singer Fred Astaire) made his songs ripe for mass consumption, and in Hollywood in the 1930s he was unstoppable. But he wasn’t always so straightforward. One of Berlin’s finest songs, forever associated with Astaire, is ‘Cheek to Cheek’. Kaplan, no musical analyst, turns to Philip Furia here, borrowing his observations about the song’s debt to Chopin’s Polonaise in A-flat major, Op. 53, and its double bridge, the first beginning ‘Oh, I love to climb a mountain / And to reach the highest peak’, and the second, ‘Dance with me – / I want my arms around you’. ‘Cheek to Cheek’ was written for Top Hat, which also contains ‘Top Hat, White Tie and Tails’, the song Berlin considered his best vehicle for Astaire.

Berlin’s extreme fame rests on two songs that aren’t nearly as good: ‘God Bless America’ and ‘White Christmas’. The first is the song some Americans think should be their national anthem, the latter remains the world’s best-selling record. That a Jewish immigrant should have written either is at the heart of Kaplan’s biography, which is in Yale’s Jewish Lives series. Berlin’s simple, diatonic melodies seldom display his cultural background in the way that Harold Arlen’s quite often do (Arlen’s father was also a cantor). But living in what Kaplan refers to as the American ‘waspocracy’, Berlin was always aware of his outsider status; Hollywood and Broadway were as anti-Semitic as anywhere. Mind you, Kaplan finds anti-Semitism in unlikely places. When ‘God Bless America’ is dismissed by one critic as ‘doggerel’ (which it is), Kaplan hears an echo of ‘mongrel’.

As for the ‘New York Genius’ of the subtitle, Kaplan’s fast-paced narrative conveys them effortlessly – both the ‘New York’ and the ‘genius’. This is not just a life, but a life and times, and the times were shaped, in part, by Irving Berlin himself.

Comments powered by CComment