- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Any definition of what constitutes ‘outsider art’, or art brut, is elusive. The boundaries of this ‘category’ are notoriously porous. There is no manifesto, no consistent medium, nor is it especially tied to any single period in time. However, it can be argued that outsider art is often regarded as art created by those on the margins of society, such as people in psychiatric hospitals, in prison, or the disabled. Outsider artists are also usually self-taught. For several decades, Anthony Mannix has been at the forefront of Australian outsider art, his particular qualification for the label being serious mental illness (though the term ‘illness’, as The Toy of the Spirit implores, is problematic). Mannix was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the mid-1980s, and spent periods as a patient in psychiatric hospitals over the next decade. Now based in the Blue Mountains, he has been free of schizophrenic episodes for many years.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

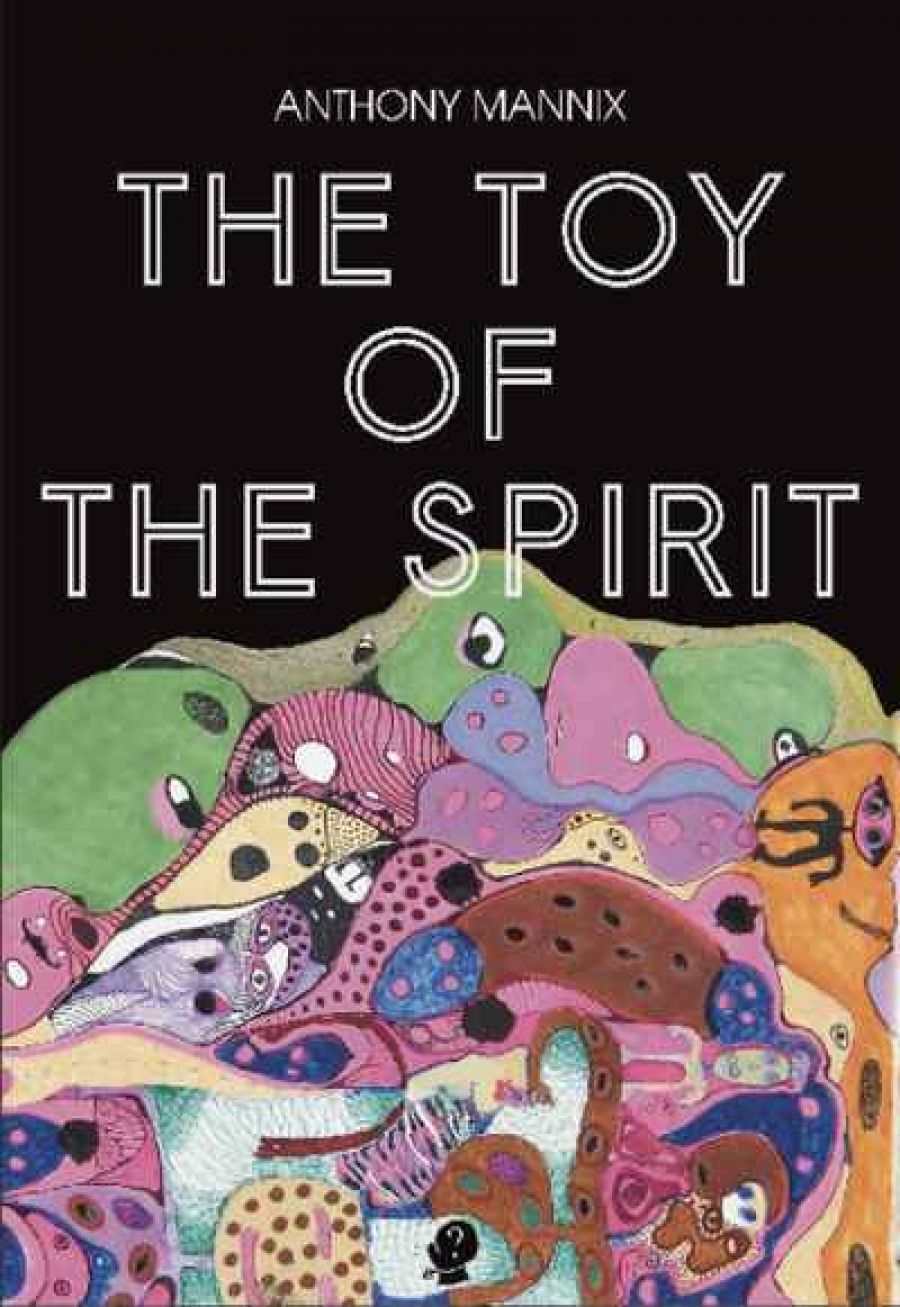

- Book 1 Title: The Toy of the Spirit

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 239 pp

Mannix’s colourful, detailed, hallucinatory drawings and paintings are extraordinary. His work is held by the National Gallery of Australia and has been exhibited worldwide; he was also featured in the historic 2017–18 exhibition at MONA in Hobart, The Museum of Everything. The Toy of the Spirit is the first collection of his writings, all of which were produced between 1985 and 1994. This is a wild and provocative adventure into the nature of psychosis and the unconscious, or, as Mannix describes it, ‘The Hidden Self which has the faculty of luminous creativity and conveys messages not only for the individual but for the future of our species.’

The book is also a meditation on what Mannix believes to be society’s warped view of mental illness and its attitude towards the mentally ill in hospital. He writes of his experience, ‘The madhouse proved an eventful place amid the unrelenting boredom that it typifies and produces as currency to dole out in useless amounts to its inmates.’

This book would not exist without the writer and poet Gareth Jenkins, who has provided studious and passionate attention to Mannix’s work. Jenkins completed a doctoral thesis on the artist in 2008, and has spent countless hours sorting through the artist’s vast collection of home-made books and texts (many handwritten) in order to decide, with Mannix, which writings to include here. The Toy of the Spirit is also punctuated by Mannix’s macabre and erotic illustrations.

Jenkins has provided an elegant and insightful introduction to this unique book. This offers essential context for understanding Mannix’s writing, and primes the reader for what to look out for amid the challenging, disorienting prose to come. Mannix’s writing can be graphic and disturbing, absurdly hilarious, and earnestly polemical; it might be described as experimental memoir or even prose poetry. Jenkins writes:

The ‘uncontrollable wild screams’ of Mannix’s individualistic voice are everywhere evident in his work, work unashamedly driven by his madness and its eroticism. Mannix admits the instability of madness into language so as to more fully communicate his experience of psychosis …

The book is organised into five chapters. The first, ‘Dedications’, features brief introductions to the characters that inhabited Mannix’s schizophrenic mind, strange and colourful figures (or even objects, or ideas) that ‘visited’ Mannix during psychotic episodes. These include ‘The Vision’, ‘the reincarnated Salome’, and ‘Tiberia and her dirty little smile’. The second chapter, ‘The Machines, or Concise History of the Machine (as far as I know them)’, is a series of whimsical illustrations accompanied by short poems or playful aphorisms. The third, fourth, and fifth chapters (‘The Skull’, ‘The Demise’, and ‘The Light Bulb Eaters’, respectively) are all, in different ways, attempts at a linguistic and metaphoric rendering of the experience of psychosis. The final chapter, ‘The People’s Odyssey’, is a series of ekphrasis-like reflections on the work of other outsider artists, including Philip Heckenberg and Janine Hilder.

A tantalising proposition throughout The Toy of the Spirit is Mannix’s bullish refutation of the idea that the altered ‘reality’ that psychosis inflicts on the affected individual is inferior to, or less valid than, conventional or consensus experience of the world. He writes, in his sprawling way:

It is that with psychosis there is a disco-ordinate expansion of reality making readily possible the working, and competently so, of direct oppositions. In terms of our desire for imbued human dynamics we should be enjoining not curing.

In an extension of this, Mannix explores the notion that the psychotic state is actually desirable, mysterious, and arousing. It is also – vital for Mannix – the locus of the creative impulse; the unconscious, accessed through psychosis, is the ‘toy of the spirit’ of the book’s title. While acknowledging the strangeness and darkness of his condition, he contends that madness is a portal to an experience that is intoxicating, revelatory, and important. He writes (in a rare experiment with line breaks):

It is society’s misconception that lunatics are unprivileged people,

that

they are somehow handicapped with an incomprehensible negative …

… it is not so, in reality they are handicapped

with an incomprehensible positive …

… almost as if they are an

evolutionary experiment for the future.

[All ellipses in original]

Readers might detect the influence of William S. Burroughs, Henry Miller, and Antonin Artaud, all of whom are name-checked in the book. Borges and Kafka are in the mix, too, while some passages come across like an X-rated Edward Lear. Mannix’s surreal landscape of the unconscious also strongly recalls the imagery of filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky.

While Mannix’s primary medium of expression may not be writing, The Toy of the Spirit is a dazzling and intricate entry point to the psychedelic playground that is his inner world.

Comments powered by CComment