- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

This beautiful book is ostensibly a conventional art monograph. In its innovative tweaking of the standard model, however, Centre of the Centre is one of the most rewarding publications about an Australian artist in recent years. Exploring two decades of ambitious work by Mel O’Callaghan, an Australian based in Paris, the book begins now, with her latest projects. In a quasi-geological enterprise, it then mines works whose interconnected seams comprise expansive video installations, sometimes including objects; wonderful paintings on glass; and, always, performed actions. Speaking about Parade (2014), Juliana Engberg noted the ‘ritualised, Sisyphean endeavour’ characterising O’Callaghan’s work.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Mel O’Callaghan

- Book 1 Subtitle: Centre of the Centre

- Book 1 Biblio: Artspace Confort Moderne and UQ Art Museum, $60 hb, 200 pp

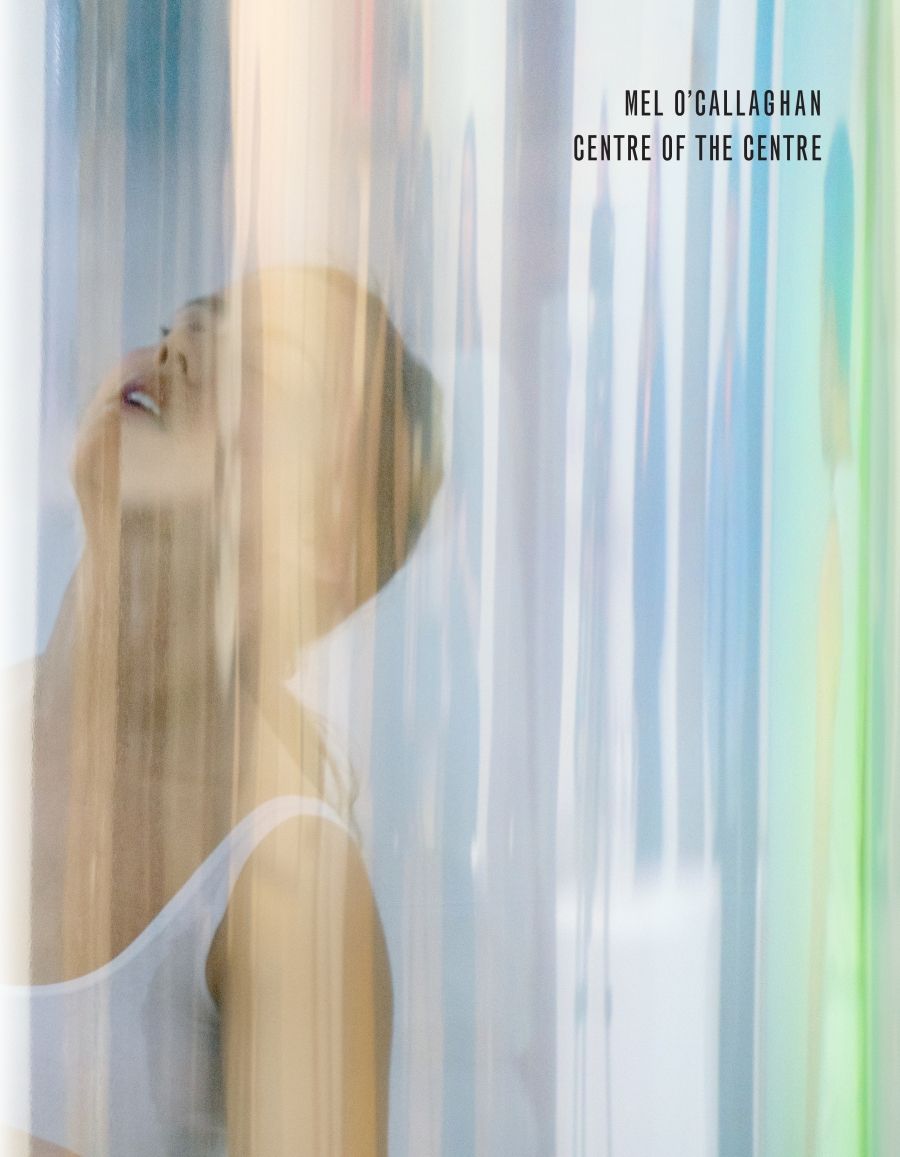

In its elegant coherence, Centre of the Centre resembles an artist’s book, conceptually driven. This is a visual project: the book is notable for unusually extensive suites of images encompassing selected projects, with gorgeous, scrupulous photographs announced by brief texts, rather than images illustrating written expositions. Installation documentation and video stills predominate; eventually, they summon something of the sensuous immersion of the works themselves. Intimate physical encounters with high-resolution images are the art book’s special gift, and Centre of the Centre’s mission. It is an exquisite experience; and the book itself is a substantial thing to hold.

Artspace’s editors Talia Linz and Michelle Newton are attentive to the artist’s theoretical freight, and it’s refreshing that word length is never mistaken for significance. At the outset, three pithy texts consider Centre of the Centre and Respire Respire, O’Callaghan’s two major recent works shown together, symbiotically. French curator Daria de Beauvais traverses O’Callaghan’s vertiginous forays into extraordinary physical locations for her videos; Sydney academic Edward Scheer discusses her longstanding investigation of trance states in ‘How to Keep Breathing’; and the distinguished American anthropologist Elizabeth A. Povinelli is interviewed by Australian curator Kathryn Weir about the artist’s fascination with the interdependence of living and non-living elements.

O’Callaghan’s ambition is not only a matter of physical scale but one of intellectual reach; her works are experimental hybrids of instinctive action and scientific research. Collaborations with scientists have seen O’Callaghan filming bird-nest gatherers in the Simud Putih caves in Borneo, researching marine biodiversity in the Verde Island Passage in the Philippines, and viewing hydrothermal vents on the Pacific Ocean floor, courtesy of a US Navy vessel. Yet the starting point for Centre of the Centre was personal, a mineral specimen owned by O’Callaghan’s grandfather, holding inside it what seems to be ancient water. Wishing to investigate the birth of geological life, O’Callaghan found her way, serendipitously, to Dr Daniel Fornari, an eminent marine geologist, who welcomes collaboration with artists as a way of expanding the horizons of younger scientists, in particular: ‘the collaborative endeavour is what science is all about’, Fornari remarked at the book’s launch at Sydney’s Kronenberg Mais Wright; art is ‘a vehicle for discussion’. Reciprocal relationships (and poetic leaps of faith) are the hallmark of O’Callaghan’s practice: at the launch, Newton noted how artist and scientist speak about the same sites in different ways. These remarkable, even improbable, collaborations speak to O’Callaghan’s awe in the face of the natural world, the wonder with which she views its processes of becoming, and, most crucially, the metaphoric beauty she finds there – the paradox of living water within the rock.

Centre of the Centre is undoubtedly a labour of love. It marked the exhibition of the two new works at Le Confort (Poitiers, France) and the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design in Manila in mid-2019, at Artspace Sydney (August 2019), and the University of Queensland Art Museum (February 2020). It accompanies a national tour of the works by Museums and Galleries of NSW, now on hold until 2021. The book would not have been possible without the driving energy of Artspace and its exhibition partners, as well as generous commitments from a slew of private and institutional sponsors and contributors, including the artist’s gallerists: the acknowledgments page reveals the protean effort required to birth such an exceptional, even lavish book, but in fact this is typical of how art publishing happens today, at least in this country. Even before Australia’s cultural life went into limbo in March 2020, art publishing in Australia was precarious. With small print runs and prohibitively high costs, contemporary art books are becoming more rare every year. Several important art publishers have closed, and vanity publishing aside, only major museums can now afford the illustrated books that were once commonplace, and then only when sales are boosted by blockbuster exhibitions: think Ai Wei Wei or, infinitely worse, KAWS (both at the NGV). Yet art books remain crucial. This exquisitely considered book shows how publications support the claims of Australia’s excellent contemporary artists to national and, importantly, international attention. Under Alexie Glass-Kantor’s leadership, Artspace is an energetic publisher for solo Australian artists showing in major international exhibitions and art museums. Centre of the Centre is an integral part of contemporary cultural production, rather than a retrospective assessment, and, significantly, writers on individual works, such as Alexandra Pedley, Joäo Silvério, and Peta Rake, are studio and curatorial colleagues who have been involved in their development.

But this achievement is fragile. How will publishing energy be sustained after 2020 without renewed government commitment, and when Australia Council support for the remaining Australian art journals and for many distinguished literary journals, including ABR, has been terminated? This is the moment to rethink the country’s cultural life – urgently.

Comments powered by CComment