- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Classics

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

What is the value of useless knowledge? One of the by-products of the rise of artificial intelligence is that the realm of what one really needs to know to function in society is ever shrinking. Wikipedia makes learning facts completely redundant. Pub trivia competitions now seem a fundamentally anachronistic form of entertainment, like watching a jousting tournament in the age of artillery. One can appreciate the skill, but one also knows that its time has come and gone.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

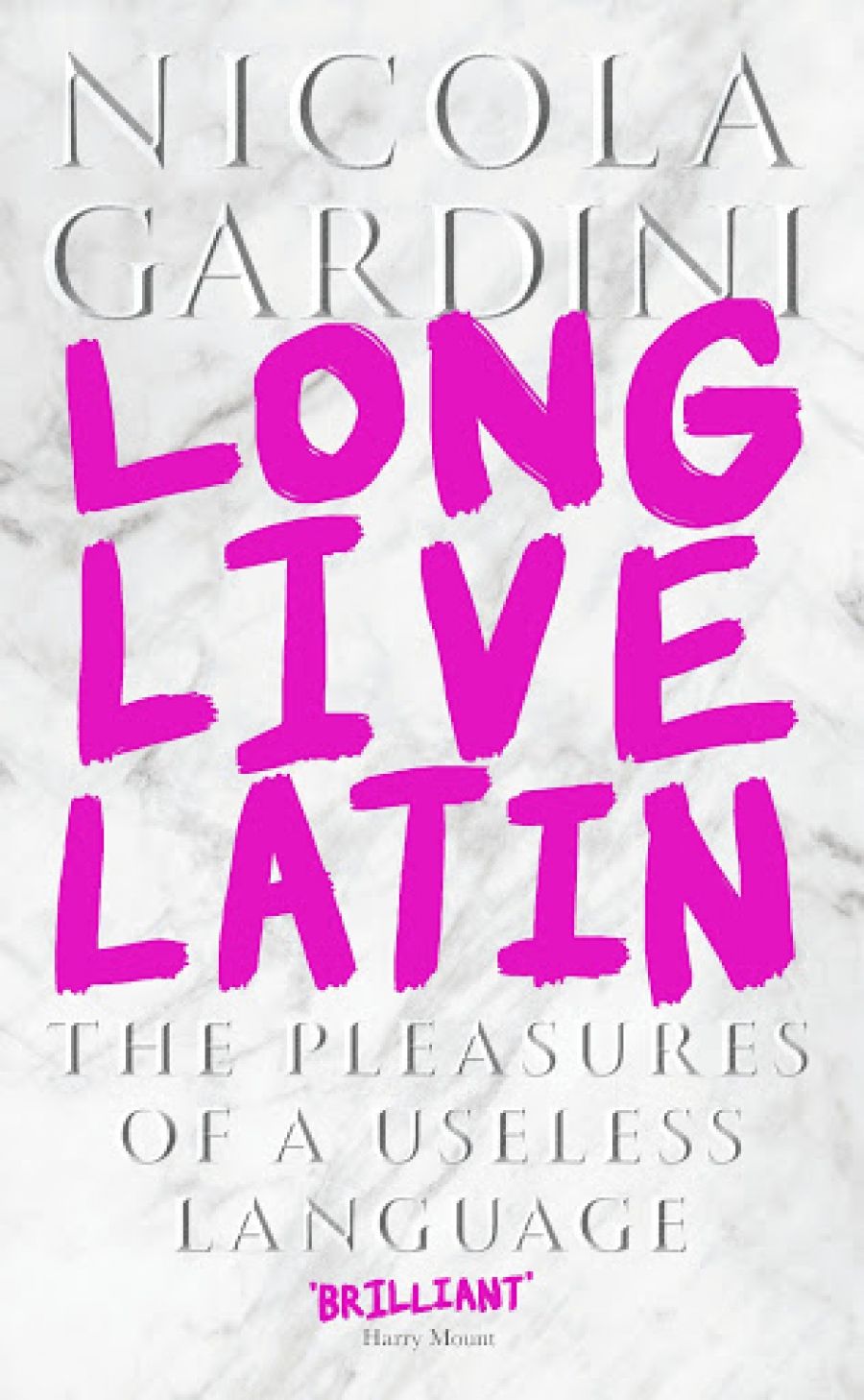

- Book 1 Title: Long Live Latin

- Book 1 Subtitle: The pleasures of a useless language

- Book 1 Biblio: Profile, $32.99 hb, 254 pp

- Book 2 Title: Vox Populi

- Book 2 Subtitle: Everything you wanted to know about the classical world but were afraid to ask

- Book 2 Biblio: Atlantic, $27.99 pb, 319 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

.jpg)

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

.jpg)

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_Meta/April_2020/unnamed (1).jpg

Against this background, going to the tremendous effort of learning a ‘dead’ language like Latin seems a ludicrous proposition. Yet, in the figure of Nicola Gardini, it has found its most eloquent and persuasive defender. His Long Live Latin: The pleasures of a useless language is an extremely personal account of the delights that learning Latin has given him from the time he first encountered the language as a boy in Milan. Gardini has no truck with any utilitarian arguments for learning a language. He is unimpressed by the suggestion that learning Latin imposes discipline, helps train the memory, or makes us think logically and with precision. If this is the desired aim, why not learn maths or algebra? There is only one reason for learning Latin: it makes our life richer and more beautiful.

Gardini illustrates this principle through a series of encounters with key Latin authors. From Ennius to St Augustine, no major figure is ignored. Each brings something different to the table. For example, Cicero established Latin as ‘a language of truth and justice’. Catullus taught it how to be sexy. Lucretius gave Latin a clarity that allowed it to perfectly capture everything from the profound emotions of a cow mourning for its lost calf to the physics of the universe. Gardini shows how each author engages with the nature of the world and the place of man within it. Attentive to form as much as content, he shows how their solutions are as stylish as they are profound. He makes you painfully feel all the nuances that are lost in translation.

Along the way, Gardini does not hesitate to point out the instances where Latin vocabulary has impacted on English. This, too, is part of the joy of learning Latin. Recovering the origins of words allows you to make connections between meanings and associations that have been lost. ‘Thanks to Latin, every word I knew doubled in sense. Beneath the garden of everyday language lay a bed of ancient roots,’ he writes.

The book is a paean to the importance of being able to carve out time to retreat from the world and inhabit another time and place. It opens with a letter from Machiavelli, who describes how when reading Latin authors he steps ‘into the ancient courts of ancient men, where a beloved guest, I nourish myself … and for four hours I feel not a drop of boredom, think nothing of my cares, am fearless of poverty, unrattled by death’.

Such a withdrawal should not be confused with escapism. The purpose of this retreat is to return energised to face the world, equipped with the skills to face its problems head on. Out of Machiavelli’s sojourns in these ancient courts would emerge The Prince, a work unrivalled for the way it engages with life’s brutal realities. Confronted by the death of a journalist friend in Iraq, Gardini found it was Seneca’s Consolatio ad Marciam, an essay written around 40 ce to console a mother on the death of her son, which gave him the strength to endure. ‘Through Seneca I was able to speak … he showed no fear in speaking, not even when faced with the greatest of losses, the death of a loved one. And in truth, why be silent before death? Why pretend that only sobbing and silence are worthy? Words are life.’

Gardini’s discussion of Latin is unashamedly rosy-coloured, and a similar romanticism infuses Peter Jones’s Vox Populi: Everything you wanted to know about the classical world but were afraid to ask. For many years, Jones has written a column in the Spectator, pointing out the similarities between ancient and modern life. In this book, he aims to provide a short guide to the highlights of the civilisations of ancient Greece and Rome. This accessible survey covers everything including philosophy, history, architecture, archaeology, politics, and art. Inevitably, the discussions are cursory, but the work cannot be faulted for its breadth.

The topics are independent of one another, so it is an easy book to dip in out and out of. Chapters are subdivided into discrete subsections, few longer than a couple of pages. Text boxes with discussions nestle among the main text. Translations of primary sources jostle alongside historical commentary. At times, it all feels a bit haphazard. The book reads like the notebook of your very learned uncle. The work is written for the general reader, but even if you know a lot about the ancient world, there are new things to discover. For example, I was surprised to learn that the way to establish archaeologically whether a rabbit is wild or domesticated is to examine its diet. If you discover that it has been eating its own faecal matter, it is domesticated. Apparently, this is something that only rabbits in hutches do. Useless knowledge? Probably. Although it does make me revisit all the times I held up and kissed my cousin’s pet rabbit.

The word ‘isolation’ is ultimately derived from the Latin word insula, meaning island. As it looks like we are set to endure months of isolation, mentally retreating to the island sanctuary of classical antiquity seems a desirable plan. As these books demonstrate, it will be a far from barren place.

Comments powered by CComment