- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australian Galleries opened in Melbourne in June 1956. One year later, Andy Warhol established Andy Warhol Enterprises in New York. Warhol’s art of making money became an art form in itself, with the artist elaborating that ‘good business is the best art’. Gallerists Anne and Tam Purves would have agreed. This husband-and-wife team took selling art seriously and introduced a professionalism unlike anything that had existed in Melbourne. Their new modern enterprise occupied a converted front section of their Derby Street paper-pattern factory in the working-class suburb of Collingwood. While the couple had no experience in art dealership or gallery management, they were confident that the arts were ready for something different. Anne, accomplished in commercial design, had considerable artistic aspirations, while Tam merely transferred his well-established business acumen across the factory threshold into their smart new premises. As with any business venture, timing was important, and they capitalised on the leverage that the 1956 Olympic Games brought to Melbourne.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Australian Galleries

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Purves family business: The first four decades 1956–1999

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Galleries, $89.95 hb, 320 pp

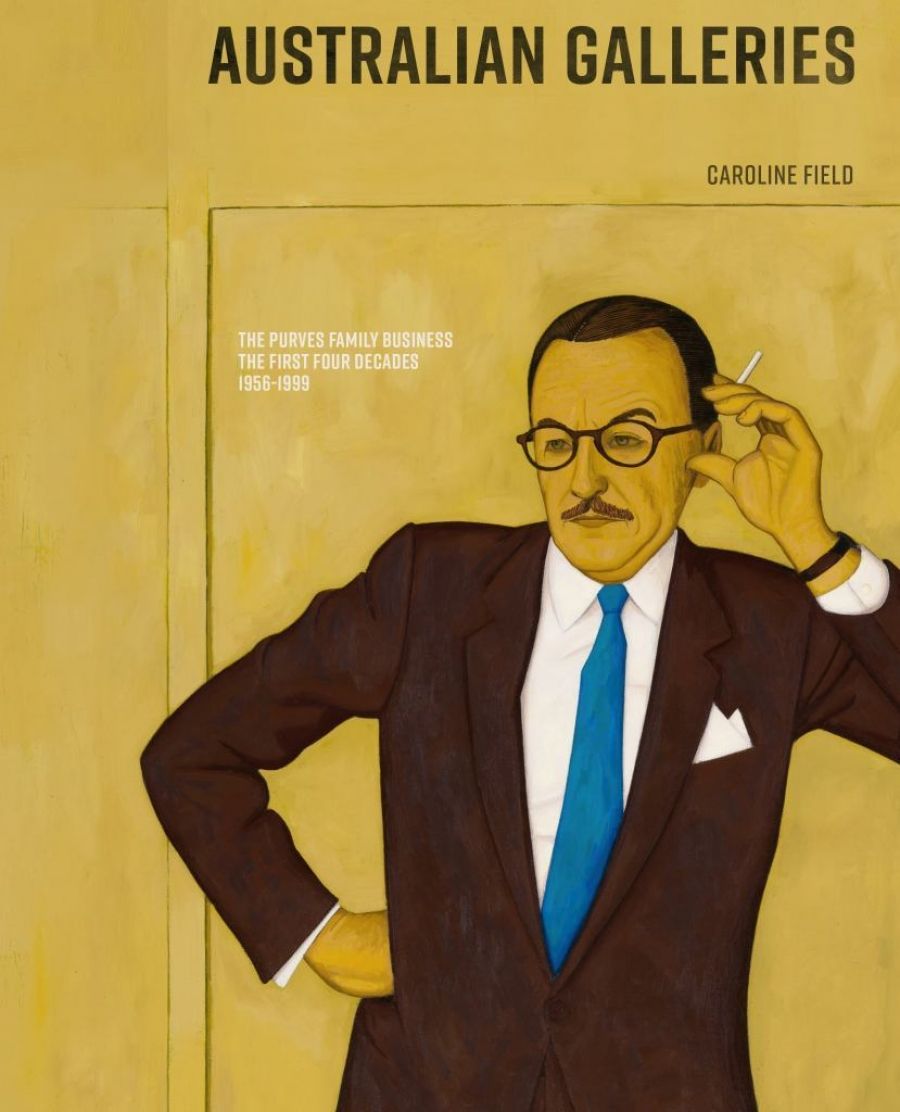

John Brack’s portrait of Tam Purves graces the cover of this elegantly produced book, capturing a poised businessman, his sleek, Brylcreemed hair, steady stare, and cigarette in hand redolent of 1950s debonair masculinity. Arthur Boyd’s expressionist portraits of Anne, all four, adorn the back cover. A sophisticated woman with a scrutinising eye for assessing the cultural landscape, Anne emerges in this history of Australian Galleries as the real mover. Tam may have been the financial rudder who negotiated loans for artists and deals with clients, but it was Anne who cajoled temperamental artists while successfully propelling modern Australian art into a conspicuous and profitable position, a role that absorbed her for the rest of her life.

The postwar Melbourne art scene, according to Inge King, resembled a glass of flat beer, but by the mid-1950s a more optimistic mood prevailed. Art and culture, the new director of the National Gallery of Victoria Eric Westbrook proclaimed, were for everyone. The Herald Outdoor Art Show in the Treasury Gardens and Westbrook’s modernising agenda confirmed this. The architect Robin Boyd promoted functional domestic planning with his Small Homes Service, and the Purveses adopted his modern concept of architectural aesthetics by commissioning him to design their home. Promoting art and lifestyle as a desirable combination, Anne claimed, suited ‘a general broadening’ and ‘awareness of a richer cultural and more stimulating life’.

Arthur Boyd, Anne Purves, Yvonne Boyd, Stuart Purves, and Janine Wilder, with Jamie Boyd's work in the background, 1993 (photograph via Australian Galleries)

Arthur Boyd, Anne Purves, Yvonne Boyd, Stuart Purves, and Janine Wilder, with Jamie Boyd's work in the background, 1993 (photograph via Australian Galleries)

Art-world rivalry kept the Purveses on their toes. The Gallery of Contemporary Art, which opened four days before Australian Galleries, Violet Dulieu’s gallery, Kym Bonython’s galleries, and Joseph Brown’s dealership all helped maintain a competitive edge. Shortly after Australian Galleries began operating, the Peter Bray Gallery at 435 Bourke Street closed. Run by Helen Ogilvie from 1949 until 1956, it represented established and emerging artists – John Brack’s iconic The bar was purchased for ninety guineas in 1955, and Inge and Grahame King held their first exhibition there. With news of Ogilvie’s departure for London, the Purveses quickly secured the best, adding John Brack, Charles Bush, Daryl Lindsay, Ian Fairweather, Inge King, and Sidney Nolan to their distinguished stable.

As Caroline Field notes, ‘the art of acquiring was also developing, and the pool of buyers had increased considerably’. The boom decade of the 1950s saw big industrialists and multinationals enter the art market. When art and business intersect, art becomes a financial instrument. An enviable blue-chip modern collection was a banner of success, and the Purveses tapped into this pool, aiming for the higher ends of the market. Society connections, name-dropping, and art transactions lend a note of snobbery to this book, but such disclosures were commonplace in the postwar decades. This changed when prosperity pushed art prices up and art-crime increased, particularly as a burgeoning secondary art market and auction sector developed. Fortunately, Australian Galleries kept good records and photographic archives of all works that passed through its premises, setting a sound practice for monitoring provenance, authenticity, and fakes.

Apart from brief biographical accounts of Anne’s and Tam’s respective family backgrounds and periodic snippets on their children, including Stuart’s maturing from an energetic schoolboy to an ebullient partner in the gallery, Field deftly weaves a substantial chronicle of personalities, exhibitions, and, besides a few banal quotes, illuminating opinions by artists, collectors, and critics. Certain issues might have been better contextualised by consulting recently published accounts of historical events in Australian art. Bernard Smith, for example, did not overlook Fred Williams for his Antipodean group; Smith’s selection was calculated and politically complex. Even Noel Counihan, one of the finest figurative artists, was not invited because of his hard-line communism. Given the climate of the day when red-baiting was at its most virulent, it is to the Purveses’ credit that they permitted the odd Communist Party meeting on their premises. Margaret Carnegie’s private collection was more than a ‘hobby’; it was a serious passion. Operating independently of dealers may have been a thorn in the Purveses’ side, but Carnegie was also gathering information on artists for Smith’s survey Australian Painting (1962).

The value of this book lies in its extensive use of Australian Galleries’ magnificent archive and Anne Purves’s ‘Art Notes’. As a woman in the art world, she knew that a degree of toughness was necessary, and her perceptive insights and astute comments – ‘one had to feel it through the pores of your skin’, as she told me in a 1998 interview – are further enriched by Stuart Purves’s frank reflections on the struggles, tragedies, and victories of this family business.

Comments powered by CComment