- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Amid all the hoopla surrounding the centenary in 2019 of the Bauhaus – naturally more pronounced in Germany – it is gratifying to see such a fine Australian publication dealing with the international influence of this short-lived, revolutionary art and design teaching institute. Bauhaus Diaspora and Beyond – written by Philip Goad, Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, Harriet Edquist, and Isabel Wünsche – explores the Bauhaus and its influence in Australia.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

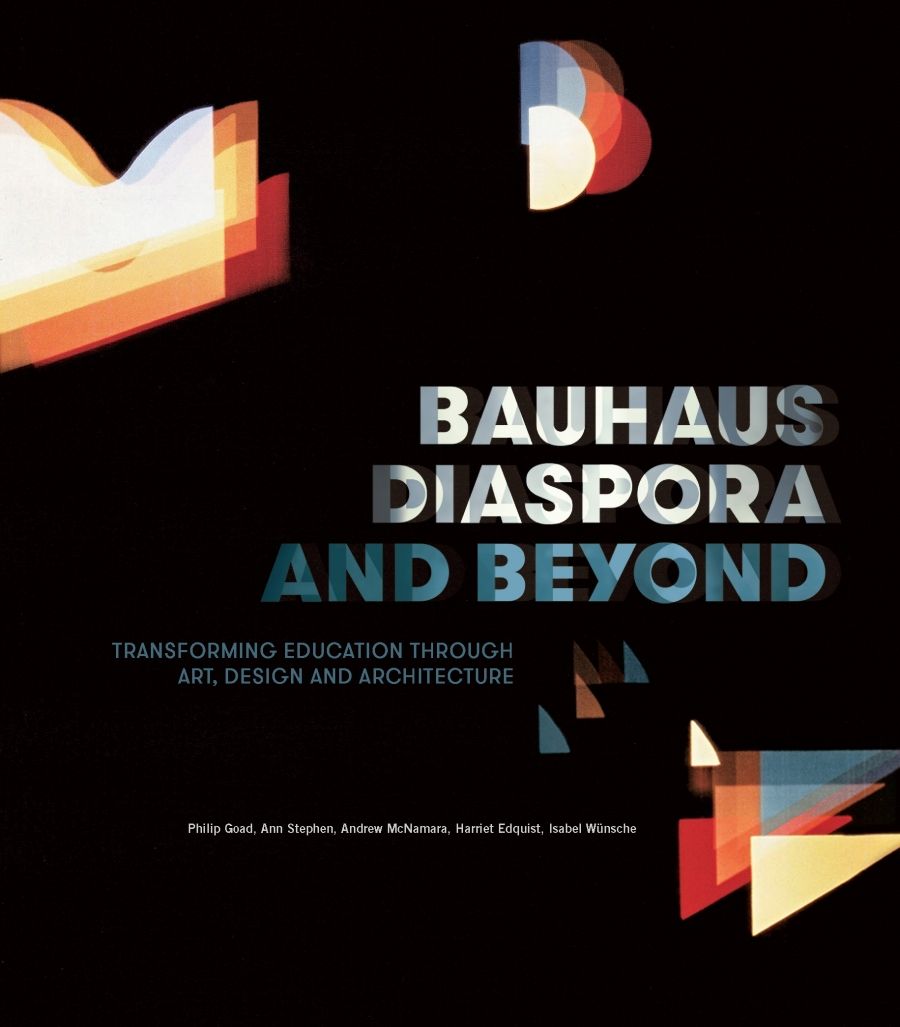

- Book 1 Title: Bauhaus Diaspora and Beyond

- Book 1 Subtitle: Transforming education through art, design and architecture

- Book 1 Biblio: The Miegunyah Press, $64.99 pb, 288 pp

The architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Weimar State Bauhaus, around 1919 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

The architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Weimar State Bauhaus, around 1919 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

The book’s subtitle, Transforming education through art, design and architecture, is significant, for it is in the educational realm that the authors convincingly argue that the Bauhaus strongly influenced Australian art and design from the 1940s. Unlike the United States, where Breuer, Gropius, and Van der Rohe lived and worked from the 1930s, and where they designed buildings, and taught, Australia has no buildings designed by Bauhaus architects. Still, as Bauhaus Diaspora and Beyond amply documents, the Bauhaus connections to Australia were strong. Gropius visited Australia in May 1954. He attended the fourth Annual Convention of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects in Sydney, and then he visited Melbourne. In the visual and graphic arts, the most prominent Bauhäusler to live, work, and teach in Australia was Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack. Though not well known outside art and art-teaching circles, Hirschfeld Mack trained and taught at the Weimar Bauhaus. His 1963 Melbourne-published The Bauhaus: An introductory story was one of the first English-language postwar accounts of the Bauhaus.

The diaspora occurred because of the rise of German fascism and the Nazis’ hatred of modernism, Jews, political radicals, and anyone else who did not toe the party line or conform to their repulsive ideology. Many of the artists covered in the book left Germany and elsewhere in Europe during the 1930s, often going first to England, only to be declared enemy aliens when war broke out. Australia does not appear to have been their first choice of asylum, and who can blame them? Hirschfeld Mack and more than two thousand others, who sailed as internees on the Dunera in 1940, were initially sent to barbed-wire confines near Hay in south-western New South Wales. Hirschfeld Mack resumed his art activities, even making a successful xylophone out of Australian hardwood. Two more internment camps followed: one in Orange, New South Wales, the other in Tatura, Victoria. Hirschfeld Mack was one of the fortunate ones. His work in the camps was noticed, and in 1942, through its headmaster, James Darling, he gained a teaching position at Geelong Grammar School. Interestingly, in 1947 Hirschfeld Mack declined a lucrative offer to teach in Chicago. Gropius considered him to be one of the few capable of carrying out the Bauhaus educational mission.

This fascinating book introduces many lesser-known figures and contextualises the postwar art scene in Australia. It is divided into three sections: Origins; Diaspora; And Beyond. The early chapter ‘Reform Education and Bauhaus Pedagogy’, by Isabel Wünsche and Wiebke Gronemeyer, forms an excellent introduction to the Bauhaus, the complexity of its changing teaching program, and its genesis and closure. And Beyond, the longest section, covers the Bauhaus influence in Australia through teaching methods and production. These methods influenced many educators and art schools and shaped the production of metalwork, jewellery, textiles, sculpture, printmaking, and architecture. This was particularly evident in Melbourne and Sydney, where most of the Bauhäusler settled and taught and where their work was exhibited. Ann Stephen gives a detailed and fascinating account in her forensic reconstruction of the 1961 Gallery A landmark exhibition in Melbourne: The Bauhaus: Aspects and Influence.

As Fiona MacCarthy reminds us in her enthralling biography Walter Gropius: Visionary founder of the Bauhaus (Faber & Faber, 2019), the seventy-year-old architect visited Australia in 1954 and received an honorary doctorate from the University of Sydney. He met young architects like Harry Seidler and Robin Boyd. At the Sydney ceremony, Gropius delivered his address ‘Is There a Science of Design?’ to an audience of nearly one thousand people. The Age described Gropius as ‘the world’s most famous living architect’. While there are numerous good accounts of the Bauhaus available in English, as a biographer MacCarthy focuses on the personalities and interrelationships, bringing intensity and richness to otherwise familiar territory. (One wonders what insights MacCarthy’s own marriage to David Mellor, one of the most successful British designers of his generation, gave her in tackling Gropius.) The nuanced year-by-year account of Gropius’s life with the Bauhaus and afterwards in the United Kingdom and the United States is gripping. His energy and drive were phenomenal, and he was clearly a charismatic man. Gropius was at the centre of European modernism; he interacted with many of the leading figures both professionally and socially: Klee and Kandinsky were witnesses at his wedding to Ilse Frank in 1923, following his divorce from Alma Mahler. MacCarthy draws on her skills as a distinguished biographer and design historian to create a rounded portrait of this pioneer of modern design.

Comments powered by CComment