- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Philosophy

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

From the Man’s horse ‘blood[ied] from hip to shoulder’ in Banjo Paterson’s ‘The Man from Snowy River’ (1890) to the kangaroos drunkenly slaughtered in Kenneth Cook’s Wake in Fright (1961), non-human animals have not fared well in Australian literature. Even when, as in Ceridwen Dovey’s Only the Animals (2014), the author’s imagination is fully brought to bear on the inner lives of animals, their fate tends towards the Hobbesian – ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’ – reflecting back to us our own often unexamined cruelty. The rare exceptions, such as J.M. Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello (2003), incorporating a fictionalised series of animal-rights lectures, serve only to point up the rule.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: The Grass Library

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $26.95 pb, 224 pp

It’s no surprise that our literature, like the brutal and brutalising settler-colonial culture from which much of it emerges, should have historically regarded animals as objects rather than subjects. That they do not feel pain as we do – that, after Heidegger, they do not even die but merely ‘perish’ – is one of many convenient fictions that, despite potentially game-changing advances in the study of animal sentience, continue to legitimise their silencing and instrumentalisation at our hands (per capita, more meat is consumed in Australia than in any other country except the United States). Unlike in indigenous societies, we hold animals, when we deign to think of them at all, in an attitude of ambivalence or contempt rather than reverence, making lavish exceptions for the pets whose company we could scarcely do without.

David Brooks’s The Grass Library is, in part, a response to our culture’s failure to grapple with these complexities, its genesis the author’s conversation with ‘a vegan friend in Western Australia’ (fellow poet John Kinsella, not named in the book) about the poor rap given to animals in Australian literature. In a later conversation with Kinsella, Brooks lists some of the things he wants to write about: the animal in philosophy; the problems inherent in writing about animals at all; and, notwithstanding Virginia Woolf’s ill-fated attempt at a biography of a dog (Flush, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s cocker spaniel), his adopted ten-year-old fox terrier cross, Charlie. Unsurprisingly, the resulting book – the second, after Derrida’s Breakfast (2016), of a proposed sestet or septet on the lives of animals – is not easy to classify, spanning modes biographical, epistolary, polemical, and literary-critical. Happily, like the non-human animals who are its subjects, the book is also deeply companionable. Brooks’s prose, even where it has the feel of a barely edited diary or thrumming animal-rights treatise, is warmly lyrical.

Early in The Grass Library, Brooks describes our contradictory standards when it comes to non-human species as ‘doubling’, a term he borrows from Robert Jay Lifton’s The Nazi Doctors: Medical killing and the psychology of genocide (1988):

barbarity itself begins with the thought that we are so different from the creatures we live amongst that we cannot know or even hazard how they feel. This is not only a lie to ourselves, for in many cases in the experience of almost all of us, we do know how some animal or other feels (at home the scientist knows how his/her dog feels. And yet ‘officially’, in the laboratory – this phenomenon is known as doubling – has no idea …

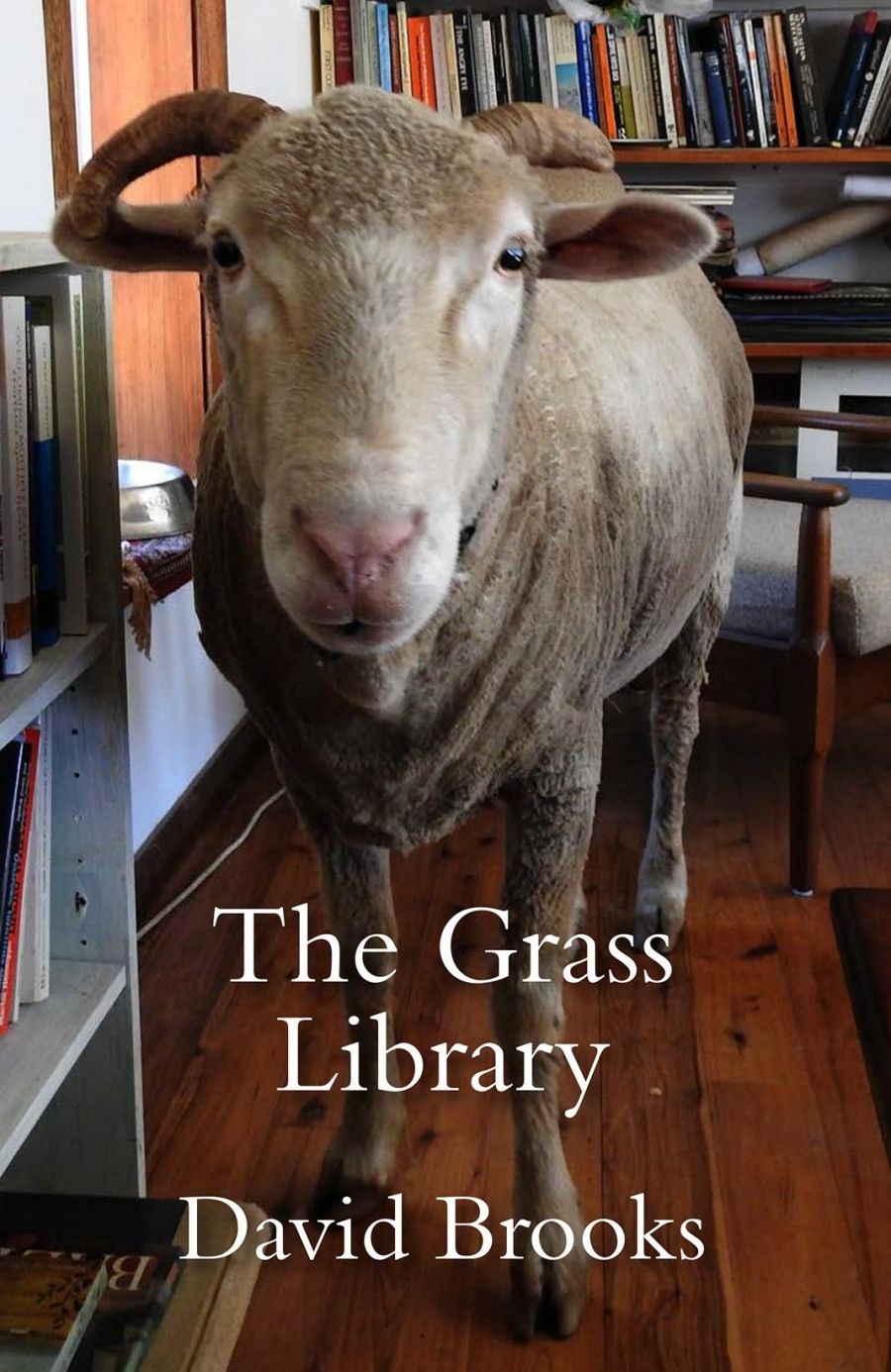

Orpheus Pumpkin in the writing-room doorway (photograph by David Brooks)

Orpheus Pumpkin in the writing-room doorway (photograph by David Brooks)

In a sense, The Grass Library is a record of Brooks’s own laboratory for the study of human–animal relations, a small farm in the Blue Mountains he shares with his partner, whom he calls ‘T.’, and a colourful menagerie of animals to which the book is dedicated: the neurotic but good-natured Charlie, and the idiosyncratic sheep Henry, Jonathan, Jason, and Orpheus Pumpkin (T. disapproves of Brooks’s preference for more literary-minded names). There are also chapter-length discursions on rats and snakes (‘“humane” traps this time,’ Brooks writes), and wild ducks, five of whose ducklings drown in the couple’s swimming pool in one of the book’s more harrowing passages.

It’s no surprise that our literature, like the brutal and brutalising settler-colonial culture from which much of it emerges, should have historically regarded animals as objects rather than subjects

Rather than Brooks, though, it is T. – an academic writing a thesis on animal grief, or, in her language, ‘the sudden disappearance of a proximal subject’ – who begins to enact a reconsidered relationship to animals first. Tearily unable to finish a meat curry, she converts to vegetarianism, an epiphanic moment for both of them. ‘Something clanged into place,’ Brooks writes, ‘like a great door shutting, or opening. I felt cruel suddenly, exposed, deeply wrong.’ Novelistically thinking himself into T.’s consciousness, much as he will do for the animals we will be introduced to in the following pages, he concludes: ‘I suppose that’s what had just happened to her.’

The problem of how to apprehend the inner life of another being – when, as Nietzsche had it, we see everything through the human head and cannot remove it – is one that preoccupies Brooks. How to make sense of Charlie’s curious tremble, of his habit of pushing certain books under the author’s bed (he especially dislikes Rilke)? How to make sense of the seeming indifference of the duck and drake to their offspring’s plight in the pool? Our very languages and discourses, thick with expressions and ideas that reinforce our subjugation of animals – to say nothing of our deeply ingrained suspicion of anthropomorphism – limit our ability to imagine, much less articulate, possible answers to such questions. For Brooks, words are themselves a kind of violence, scarring and erasing the non-human animals we live among as surely as the physical traumas – docking, castration, euthanasia – we inflict on them as a matter of course. Observing the unshed shell of a dead nymph (the name cicada itself means ‘scar’ or ‘wound’), Brooks writes: ‘I’ve come to think of language as a kind of carapace of dangerous notions, something that will restrict us, hold us back if we don’t learn to use it with greater care and respect.’

Like Agamben and Derrida before him, Brooks chips away at the self-serving denials and falsehoods with which we think and write animals out of, rather than into, being, in the process revealing the frailness of our humanity that supposedly separates us from them. Whereas Derrida, famously, stood naked before his cat in a state of embarrassment, I found myself missing Charlie, Henry, Jonathan, Jason, and Orpheus Pumpkin almost as soon as I put The Grass Library down, my sense of being above them, to use a Derridean word, trembling.

Comments powered by CComment