- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On Boxing Day 1962, The Australian Women’s Weekly opened with a two-page spread on a new publication, Self Help for Your Nerves, by Sydney physician Dr Claire Weekes. Her four precepts for people suffering from ‘nerves’ appeared in huge, bold type: facing, accepting, floating, and letting time pass. Positive reviews followed, including one by Max Harris in ABR’s December 1962 issue. Wary of the ‘help yourself psychiatry’ genre, Harris was quickly persuaded by its ‘particular excellence’. The book went on to become a bestseller in the US and UK markets, and Weekes followed it up with four more.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

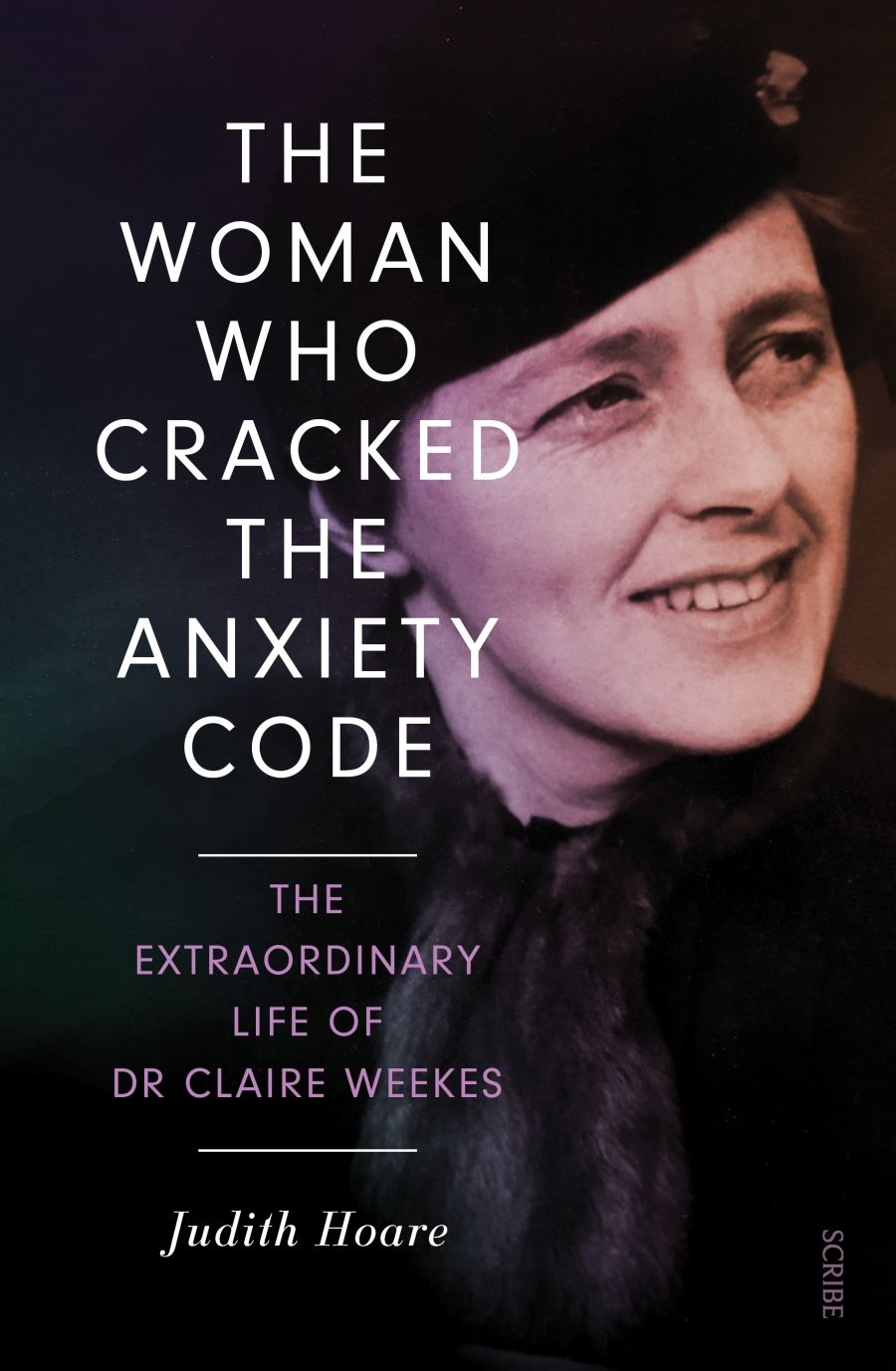

- Book 1 Title: The Woman Who Cracked the Anxiety Code

- Book 1 Subtitle: The extraordinary life of Dr Claire Weekes

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $39.99 pb, 416 pp

In her biography of Weekes, veteran journalist Judith Hoare has rescued the Australian doctor from obscurity and placed her squarely in the history of the diagnosis and treatment of anxiety disorders. Hoare had her own encounter with anxiety in her twenties, as a reporter in the press gallery in Canberra, when she became ill and run-down and developed heart palpitations. Her mother lent her a copy of Self Help for Your Nerves. Hoare was struck by the ‘sheer power of an intelligent, yet simple explanation of the mind-body connection’. She has now returned to that experience to produce a scholarly, absorbing account of Weekes’s life and work.

Dr Claire Weekes at her home in Cremorne, on the deck overlooking the Sydney Harbour

Dr Claire Weekes at her home in Cremorne, on the deck overlooking the Sydney Harbour

Hoare’s experience of anxiety parallels Weekes’s own. As a young research scientist on her way to becoming the first woman to gain a science doctorate at the University of Sydney, Weekes’s career was blindsided by illness, a misdiagnosis of tuberculosis, and six months’ isolation in a sanatorium. This left her low in mood and confidence, with frightening palpitations. Eventually, a friend’s remark helped restore her equilibrium. The friend had suffered PTSD (shell shock, as it was then called) during World War I and recognised that a racing heart could be programmed by fear, which could then fire up the ‘fight or flight’ response when it was no longer needed. This insight relieved Weekes’s symptoms and set her on course for investigating the mind–body connection.

She was already showing promise as a scientist, and had taken part in a field trip on the Great Dividing Range by Professor Launcelot Harrison to investigate lizard reproduction and its place in evolutionary patterns. The reptilian brain, with its primal survival mechanism, provided a fitting start to her work on anxiety. Soon she was on a Rockefeller Fellowship at University College, London. It would be years later, after a couple of surprising career moves, as a singer and later a travel agent, that she decided to study medicine. In the late 1940s she opened her own general practice in Bondi. She was to spend years treating patients with anxiety disorders in her surgery before penning her books and giving lecture tours in the United States and the United Kingdom. She continued to work with individuals, mostly over the telephone, until her death at the age of eighty-seven.

Weekes never trained as a psychiatrist and had no interest in writing scientific papers to cement her standing in the psychiatric fraternity, which remained somewhat sceptical of her populist approach, both in her writing and in her lectures. In her books, Weekes cut paragraphs and sentences to the bone, used layman’s terms, and focused on key concepts, providing simple advice, practical tools, hope, and encouragement. She had found her vocation. Hoare, a consummate writer, shows admiration for Weekes’s powers of communication and her ability to use them to ‘change lives, save lives, and change history’.

Charles Darwin and Sigmund Freud play prominent parts in the story, as do several distinguished scholars and mentors. Weekes’s understanding of the mind–body connection harked back to Darwin and the nineteenth century, and connected with Walter Bradford Cannon’s work on fear and its source, the autonomic nervous system. In her earlier field trip to the Great Dividing Range, Weekes had been following in the footsteps of the young Darwin, who was captivated by Australian reptiles. Ironically, it transpires that Darwin, that intrepid scientist, suffered from palpitations and was convinced he had heart disease. He spent much of the five-year voyage on HMS Beagle as a semi-invalid.

This is just one of the gems unearthed in Hoare’s extensive research and woven seamlessly into the complex narrative of Weekes’s professional and personal journey through the twentieth century. Judith Hoare left her position at the Australian Financial Review to spend the last five years writing this, her first book. Displaying the hallmarks of an accomplished journalist, this is a fascinating biography of a free-spirited and innovative woman, an insight into the history of evolutionary and psychiatric theories, and an introduction to Weekes’s methods and her books.

Comments powered by CComment