- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Westerbork is the name of a transit camp located in the Netherlands. You transitioned from Westerbork to your final destination by means of the Nationale Spoorwegen (the national railways). Eddy de Wind, a Dutch Jewish psychiatrist, met his future wife, Friedel, in Westerbork. Both were sent to Auschwitz in 1943. Eddy was sent to Block 9 as part of the medical staff, Friedel to Block 10 to work as a Pfleger (nurse). Block 10 was administered by the Lagerartz (senior camp doctor), Josef Mengele.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

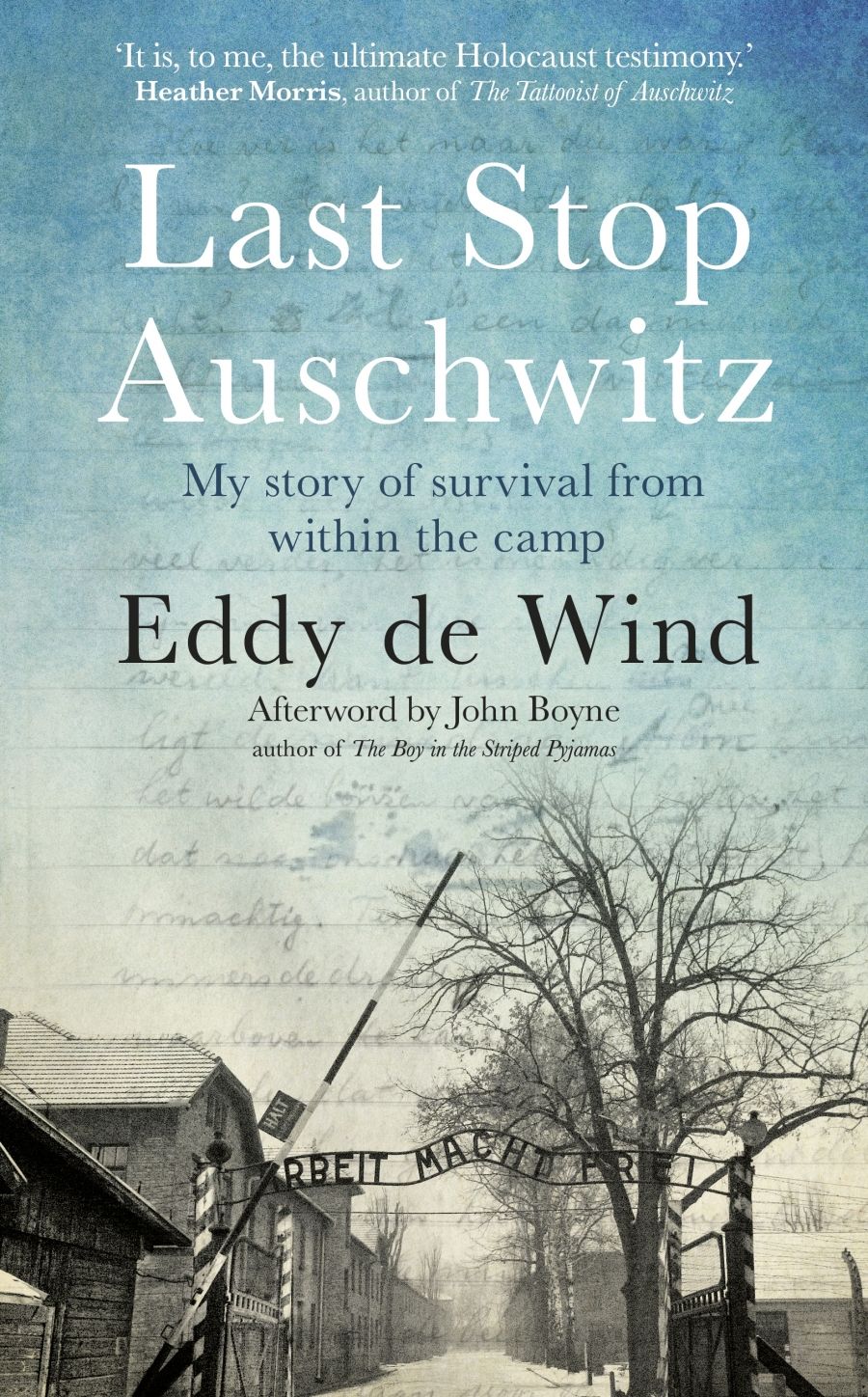

- Book 1 Title: Last Stop Auschwitz

- Book 1 Subtitle: My story of survival from within the camp

- Book 1 Biblio: Doubleday, $29.99 pb, 260 pp

She did. The couple eventually reunited, but in the end the marriage failed. For Eddy and Friedel, there was before Auschwitz, Auschwitz, and after Auschwitz. Both were profoundly damaged. Neither ever truly recovered.

Eddy de Wind (photograph via Penguin Books Australia)

Eddy de Wind (photograph via Penguin Books Australia)

De Wind wrote his account in pencil in a thick notebook. So traumatised that he was unable to write in the first person, he invented an alternative identity called Hans Van Dam – an ordinary Dutch name for an extraordinary survivor. The writing cannot be considered perfectly crafted. Its value lies in the raw, visceral effect, the attention to detail so powerful that no fictional account can possibly come close. As far as anyone knows, this is the only book to have been written from inside the belly of the beast.

One vignette in this remarkable book is unforgettable. The Nazis have departed, it is a glorious sunny day, and for the first time de Wind is free to roam about the camp. He climbs a tower and surveys the complex. ‘A little to the left lay Birkenau … It had been run according to an extermination system of incomparable perfection.’ Elsewhere were the Krupp and IG Farben factories; efficient industrialists paid the SS six marks for every worker able to be utilised until they became too ill to work, whereupon they were dispatched to the killing chambers.

De Wind was all too aware that the Jews were the playthings of the Nazis, but they were unaware that this young, highly intelligent psychiatrist was studying them, storing evidence for an eventual reckoning. One of his vital sources was Friedel, who looked after girls who had been subjected to experimental sterilisation procedures resulting in horrific injuries. One month later the girls had their ovaries removed, ‘to see what kind of condition they were in’. In another experiment, a cement-like liquid was injected into women’s uteruses while they were X-rayed. Many of these ‘experiments’ were funded by Farben on the pretext of finding a suitable mass-sterilisation method.

Josef Mengele has achieved a notoriety second only to that of Adolf Hitler or Adolf Eichmann. His presence pervades this book, yet he is never mentioned by name. It is possible that de Wind didn’t know it. For the inmates of concentration camps, it was levels of authority that mattered not names. The staff in Block 10 lived in fear of being experimented on. They were useful as long as they could work. When Friedel becomes ill, de Wind approaches the Lagerartz and begs for her life. Mengele agrees. De Wind does not think better of the Nazis for their occasional acts of kindness:

The youngsters have been raised in the spirit of blood and soil. They don’t know any better. But those older ones like the Lagerartz show through those minor acts that they still harbour a remnant of their upbringing. They didn’t learn this inhumanity from an early age and had no need to embrace it.

After the liberation of Auschwitz, at the request of the Russians, de Wind stayed on to tend to the Dutch patients until they could be transferred to Russia. He followed the Red Army and ‘did all kinds of difficult medical things … that were actually far beyond my capabilities’.

After the war, Eddy resisted any efforts to refashion the work as a traditional memoir. He was adamant that the work should stand as is. For various reasons, publication efforts failed. De Wind became famous for his landmark psychoanalytic studies of survivor guilt; he died in 1987 without seeing this work published by a major house.

There are few Dutch Holocaust survivor accounts. Fewer than 25,000 Jews survived from a pre-war estimate of more than 200,000. As a child in the Netherlands, the name ‘Anne Frank’ was everywhere effectively silencing other stories. Eddy de Wind’s account is a counterbalance. There was a purpose to his survival.

I commend David Colmer’s excellent translation. Colmer has resisted the temptation to polish and has succeeded in rendering the urgency, the rawness, and the lyricism of the original work.

Comments powered by CComment