- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Feature-length documentary film has seldom been as commercially successful as fictional drama at the box office. Nevertheless, Nick Fraser tells us that it is now ‘common to hear documentary film described as the new rock ‘n’ roll’. It is exactly this energy, influence, and popular appeal of documentary that Fraser wants to tap into with this book. He seeks to further enliven the documentary aficionado’s appreciation of the genre and to expand their knowledge of titles and filmmakers.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

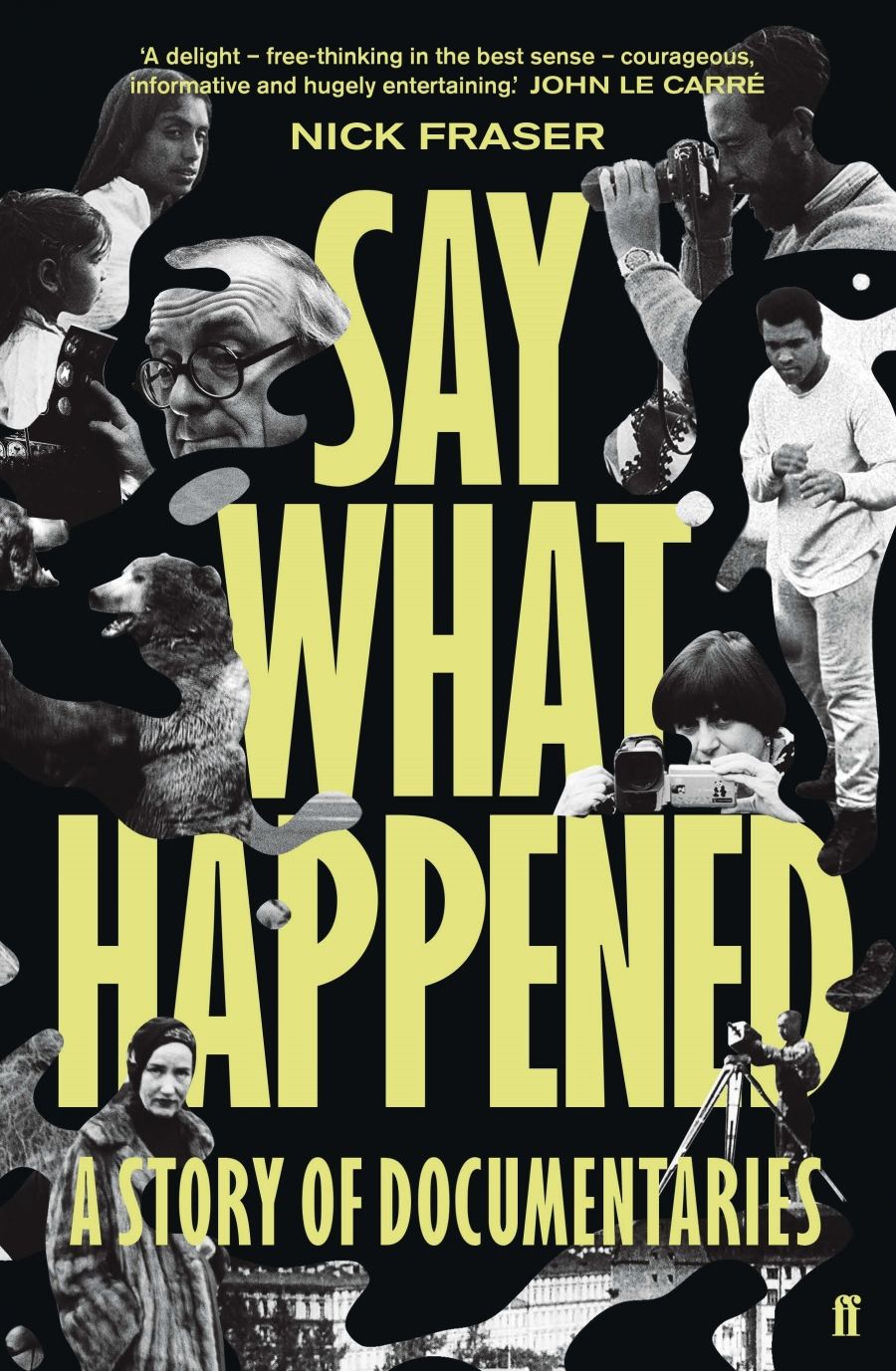

- Book 1 Title: Say What Happened

- Book 1 Subtitle: A story of documentaries

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber & Faber, $45 pb, 400 pp

Say What Happened: A story of documentaries is a selective contemplation of films and the historical moments in which they took shape. Told from a personal perspective, it winds through Fraser’s own biographical narrative. Without a clear rationale as to why certain films are left in and others left out, Say What Happened is a book for documentary enthusiasts, not students of documentary tradition and style. Fraser makes it clear that this is not an academic book. Instead, this is a reflection on Fraser’s personal interest in documentary over decades.

Fraser is well placed to write such a book. He has worked for decades as a producer and commissioning editor. He created the BBC’s Storyville, a regular television slot that commissions international feature-length documentary. Involved with Storyville for seventeen years, Fraser has won Oscars, BAFTAs, and Peabody Awards. He recounts working on documentaries such as Man on Wire, One Day in September, and Project Nim. Chapters are anchored in an intimate knowledge of media institutions (especially the BBC) and the motivations of filmmakers.

Philippe Petit in Man on Wire (photograph via YouTube)

Philippe Petit in Man on Wire (photograph via YouTube)

The most compelling insights are those that offer detail about the production or circulation of particular films. In 2014, Fraser travelled to Delhi to work on India’s Daughter, a film about the horrific rape and murder of Jyoti Singh in 2012. The case sent reverberations around the world and highlighted the problem of sexual crimes against woman in India. Fraser paints a picture of working on the film in the heat of pre-monsoonal Delhi and his role in liaising with Singh’s parents. After being banned in India, the film was released and a global storm of controversy followed. Fraser describes this episode as one of the most extreme experiences of his career. The debate he had hoped for – how rape could be more easily prosecuted – did not come to pass. India’s Daughter demonstrates the power of documentary. But the book also laments how easy it is for individual documentaries, indeed for messages, to become lost in a media sphere that has expanded exponentially in recent decades. Many examples are cited over the course of Say What Happened, but a handful of documentaries appear to cut through and stand above the rest. Marcel Ophüls’s film The Sorrow and the Pity (1969) seems to have shown Fraser how affecting and influential documentary could be. He saw this film about the collaboration between the French Vichy government and Nazi Germany in his youth; its revelations stayed with him, shaping his future aspirations.

Although at times the book describes contemporary documentary film as beset by a lack of clarity of purpose and influence, it is also critical of the new mode of ‘social impact’ documentary. These are films that are decisively produced within campaigns or activist communities and that are designed to maximise audience responses in a range of ways. Australia’s own 2040, released in 2019, is one example. For Fraser, ‘there is a line between film-making and advocacy’, and ‘you could make a film that became a campaign, but that wasn’t the same as making a film that was part of a campaign’. While this is a valuable sentiment, one that preserves the even-handed integrity of the documentary project for audiences, the range of films now produced in the impact mode offer a richness of style on its own terms. Given the intimate ties that bind the history of documentary and propaganda, moreover, it seems like an overreach to make these kinds of claims for the integrity of documentary. While such claims may vex some readers, they also signal the opinions of a powerful industry insider and thus offer compelling insight into one small facet of documentary culture.

Say What Happened forges together opinion, anecdote, and knowledge of a broad array of films and filmmakers. It wants ‘people to see docs in the present for which they are made’, rather than recount a formalised history of documentary. In this spirit, the book offers chapters on the French vérité tradition and the American direct-cinema movement of the 1960s. So much has been written about both of these and the book covers well-trodden ground; these chapters do not have the same energy as the more biographical sections. It focuses on well-known films, many of which have enjoyed at least limited theatrical release, and well-established models for commissioning documentary, especially via public service broadcasting. Despite the fact that influential new funding and distribution modes such as streaming portals and subscription television) have changed the environment for documentary filmmakers significantly, their importance is downplayed in the book. Still, Nick Fraser’s book exhibits the passion of a true documentary devotee. Connoisseurs of the genre will find it most compelling when it goes behind the scenes to reveal the humanist musings of Frederick Wiseman or the ‘raffish arrogance’ of Nick Broomfield.

Comments powered by CComment