- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Dance

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

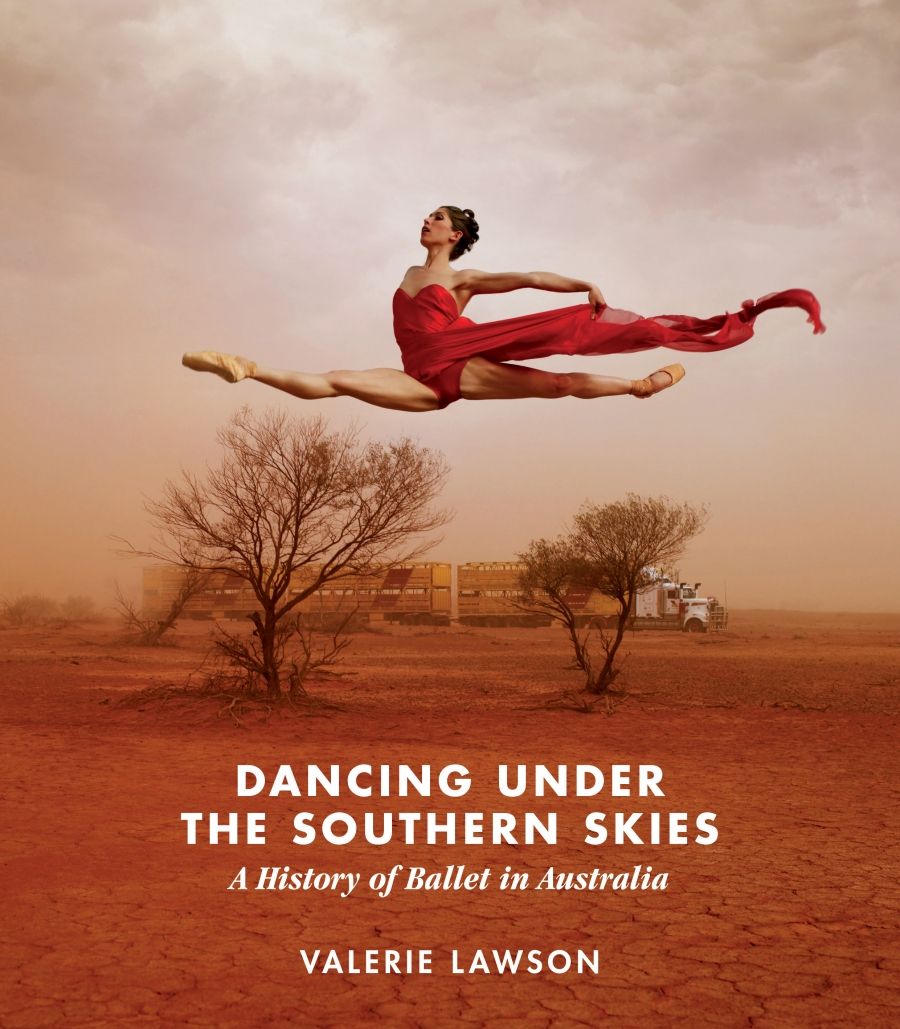

Valerie Lawson is a balletomane whose writing on dance encompasses newspaper articles and also articles and editorials for numerous dance companies. Lawson’s lavishly illustrated Dancing Under the Southern Skies, like Arnold Haskell’s mid-twentieth-century popular histories of ballet, substitutes stories about ballet and ballet dancers for a cohesive historical narrative about ballet in Australia. Portraits, images of ballet dancers posing in photographers’ studios, and ephemera are reproduced in the book; but the total sum of stage photos – of dancing – can be counted on one hand.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Dancing Under the Southern Skies

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history of ballet in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $59.95 pb, 374 pp, 9781925588743

The observation that Lawson echoes her source material – such as Haskell’s writing – is reflected in Lawson’s own preferred narratives, which revel in the theatrical blurring of ballet dancers’ lives on and off stage. For Lawson, Anna Pavlova not only interpreted a dying swan in The Swan (1905), at the end of her life she became a sick bird. Of Olga Spessivtseva – celebrated for her interpretation of Giselle’s ‘mad scene’, and who suffered a nervous breakdown in Australia – Lawson writes ‘[in] ballet, there are many dolls … some of them dance until they are destroyed, or until they destroy themselves’. The mystification of ballet history will thrill readers who value dancers’ extraordinariness, and will irritate others, including dance scholars eager to be taken seriously by fellow academics.

Gough Whitlam, Rudolf Nureyev, and Robert Helpman on the set of Don Quixote in 1972 (photograph via Australian Scholarly Publishing)

Gough Whitlam, Rudolf Nureyev, and Robert Helpman on the set of Don Quixote in 1972 (photograph via Australian Scholarly Publishing)

The trouble with Dancing Under the Southern Skies is its promise to deliver more than a balletomane’s good yarn: specifically, a revisionist history of ballet in Australia. In reality, it consists of chronologically ordered, discrete chapters, half of which concern European dancers who toured Australia from 1926 onwards, the year Pavlova first came here. The latter half of the book relates experiences of Europeans who visited then stayed, as well as Australians who came home following successful ballet careers abroad, to contribute to local ballet.

Nonetheless, Lawson suggests in a preface that she uncovers the ‘British Council’s intervention in Australian culture after World War II’; how the ‘thread that runs through’ the book is the ‘beginning and end of the intervention’. Dancing Under the Southern Skies does not strictly adhere to its own path. Nor does it convincingly show that British authorities were hostile toward ballet by Australians. Lawson refers to a supposed British exertion of power in chapter eight, in a passage on the exhibition Art for Theatre and Ballet (1940), curated by Tatlock Miller, featuring theatrical designs from Britain. No mention is made of a second exhibition in 1942, also curated by Miller, titled Australian Art for Theatre and Ballet. This weakens her argument that British influencers directly affected or contained Australian ballet.

The ill-defined British hand in Australian ballet reappears in chapter eleven, ‘The British Invasion, 1947–49’. The ‘campaign began in May 1944’, Lawson explains, ‘with a letter from a British Council representative in London to the British High Commissioner in Canberra’ expressing anxiety about the popularity of American books, music, and documentary films, but not ballet. The Rambert Ballet’s 1947 tour is portrayed as an instrument for reasserting British cultural dominance in Australia, although Lawson notes how the company quickly became a ‘two-nation troupe with more and more Australian dancers joining the company’.

Against the background of harmonious links between British ballet and (settler-colonial) Australian ballet, it is regrettably ironic that Lawson equates a British ballet’s tour to Australia with invasion. In doing so, Lawson implicitly denies Australia’s settler-colonial foundations, further positioning settler colonists and migrants as ‘natives’ defending a sovereign cultural ‘landscape’.

This blindspot limits significantly a more novel historiographical intervention in Dancing Under the Southern Skies: Lawson’s attempts to acknowledge Aboriginal histories parallel to, and sometimes intersecting with, ballet history. The book begins and ends with references to Aboriginal performance, intermittently discloses settler-colonists’ brutality (unrelated to dance) against Aboriginal people, and, conversely, construes ballet dancers’ consciousness and appropriation of Aboriginal cultural practices as empathy with Aboriginal people.

The purpose of such ‘recognition’ in a book otherwise isolated from ‘history wars’ discourse and Indigenous perspectives is made more questionable by its exclusion of Aboriginal participation in ballet: notably absent are Rex Reid’s Corroboree (1950), and Kira Bousloff’s Kooree and the Mists (1960), and Woodara (1963), non-Aboriginal ballets that appropriated (actual and fictional) Aboriginal stories and identities and featured Aboriginal performers in minor and major roles.

Lawson apologetically responds to non-Aboriginal ‘Aboriginal-themed’ ballet, stating that the ‘notion of cultural appropriation was decades away’. Indicative of the pre-eminence of settler-colonial voices, perspectives, and interests in Dancing Under the Southern Skies, such statements subvert subaltern cultural rights prior to the currency of certain academic terminology.

By contrast, passages on the Australian Ballet’s organisational history, and the positive rather than disruptive role British women played in its development, make a more valuable contribution to ballet history. Anne Woolliams and Maina Gielgud, former artistic directors discussed in the book, have previously attracted little sustained interest in dance writing. A summary of internal disputes between dancers and the company’s administrator, Peter Bahen, during Marilyn Jones’s stewardship of the Australian Ballet offers insights that would be unlikely to appear in a house publication.

Comments powered by CComment