- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

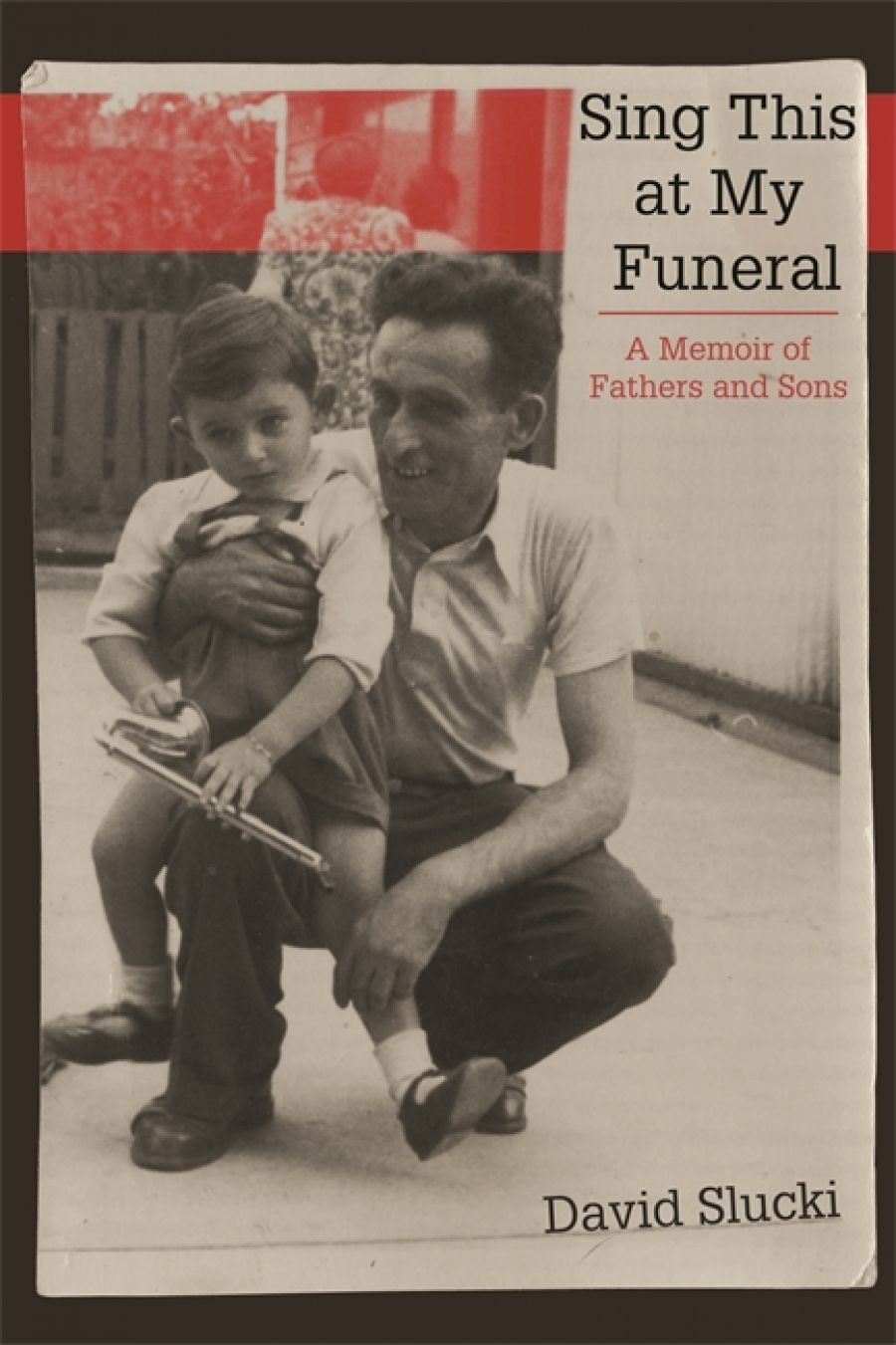

Sing This at My Funeral is not your conventional ghost story. Invoking Franz Kafka’s words, ‘Writing letters is actually an intercourse with ghosts, and by no means just the ghost of the addressee but also with one’s own ghost, which secretly evolves inside the letter one is writing or even in a whole series of letters’, this moving memoir by David Slucki gives shape to the ghost of Zaida Jakub, the grandfather he never knew.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Sing This at My Funeral

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir of fathers and sons

- Book 1 Biblio: Wayne State University Press, US$27.99 pb, 280 pp, 9780814344866

Having lost his first wife and two sons at the hands of the Nazis, Zaida Jakub arrived in Melbourne in 1950 as a European refugee. A devout Bundist (note the irony, as it is a staunchly secular, social democratic movement), he became a pillar of the Polish‒Jewish community in his adopted neighbourhood of North Carlton. The Holocaust remains, to this day, at the forefront of the Bundists’ consciousness, and they are committed to preserving its memory. This is the movement into which Jakub’s children and grandchildren were born, and the legacy they inherited from him.

Jakub in his Polish military uniform, probably during the Polish-Soviet War (photograph via Sing This at My Funeral by David Slucki)

Jakub in his Polish military uniform, probably during the Polish-Soviet War (photograph via Sing This at My Funeral by David Slucki)

In his ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, composed as he was fleeing from the Nazis in 1940, Walter Benjamin writes of an angel banished into exile and pushed toward the future, powerless to reverse the course of his flight as he observes the catastrophe that was the source of all subsequent ruins: ‘The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed.’ Slucki endeavours to do just that as he explores his relationship with the father he admired so much and the experiences of the past transmitted by his own father. He cites scientific research suggesting that DNA is modified by trauma and is thus genetically inscribed into the flesh of future generations. In open-ended questions that force readers to reflect on their own lives and roles as parents, the author asks what kind of father he would like to be to his son, Arthur, to whom this book is dedicated, and what values he would like to instil in him, given his tragic family history.

The Yiddish theatre is one of the most powerful vehicles through which the values of the Bund are transmitted to the younger generation. The chapter entitled ‘The Slucki Method’ is particularly compelling, as it probes the impact of an arts education and its role in shaping young people’s lives. The author’s father was a respected drama teacher and theatre director who inspired generations of students and aspiring actors. In 1995, he was recognised as Victorian Teacher of the Year for his innovative teaching methods. Sluggo believed in the power of the theatre to build community and enrich society, and it was there that he put his commitment to Mentschlekhkayt – treating every human being with dignity – into practice. The theatre contributed to the strong bond between father and son and to the author’s own sense of identity and professional development. Significantly, it is at the Melbourne Yiddish Theatre that he met his wife, Helen, at the age of thirteen.

Written with raw, candid feeling, this memoir attains its emotional climax not at the description of Sluggo’s sudden death at the age of sixty-seven or even of his funeral, but, rather unexpectedly, in the epilogue, when the author cites his father’s conciliatory email, sent after their most serious fight (up to that point, their relationship sounded quite idyllic). As French novelist Marcel Proust once said: ‘An artist expresses not only himself, but hundreds of ancestors, the dead who find their spokesman in him.’ David Slucki is one such artist, literally giving voice to his now-voiceless ancestors and to the numerous ghosts that accompany him on his life’s journey. Though his literary prose is vivid, the frequent shifts in register to colloquialism are at times jarring, as are the proofing errors throughout the book.

In a drive to ‘populate or perish’, Australia absorbed many migrants, including Slucki’s grandparents, fleeing Europe after World War II. As such, Melbourne – the only place in the world where the Bundist movement officially exists today – appears to be an appropriate setting for the investigation of themes such as the relationship between the past and the present and the effect of trauma on the victims’ descendants. No wonder, then, that Melbourne was also chosen by Maria Tumarkin, whose Stella Prize-nominated work of non-fiction, Axiomatic (2018), grapples with similar issues. Nonetheless, in recent years, Australia has tightened its immigration policies. Iranian‒Kurdish journalist and writer Behrouz Boochani’s recent liberation from Manus Prison raises questions about Australia’s ongoing treatment of refugees. What traumas will their children and grandchildren carry with them? Which ghosts will continue to haunt them? As Slucki eloquently puts it, ‘When you grow up amidst the scars of the past, you can’t help but be shaped by that … The ghosts don’t call ahead; they appear when you least expect them.’

Comments powered by CComment