- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his long poem The Bridge (1930), Hart Crane balances the breadth of his epic vision against a compressive energy, a ballistic sort of expression: ‘So the 20th Century – so / whizzed the Limited – roared by and left.’ Since Crane worked in an American tradition of poet–prophets that includes Walt Whitman and the undersung H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), it is tempting to grant him that. The twentieth century did roar by and go. And the 20th Century Limited, the luxurious passenger train connecting New York to Chicago, furnished it (and him) with an expression of the century’s quarrelsome momentum, its loud, emblematic modernity.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Ben Hecht

- Book 1 Subtitle: Fighting words, moving pictures

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint), $37.99 hb, 249 pp, 9780300180428

When, in 1954, Hecht published his memoir – a book that ‘bounces along’, according to Adina Hoffman, with an American brand of glee – he had long since known he would call it A Child of the Century, a reference to the historical epoch, the Broadway romp he wrote with MacArthur, and the train that whizzed him from Chicago to New York, New York to Chicago, and momentously to Hollywood. Hart Crane, incidentally, had been dead for two years by 1934. But Waldo Frank remembered him, in an allusion to William Wordsworth, as ‘a child of modern man’, a person who lived in intimacy with ‘cities, machines, the warring hungers of lonely and herded men, the passions released from defeated loyalties’. Though Crane shot through, Hecht held on, through decades that would deepen the poignancy of those same intimacies.

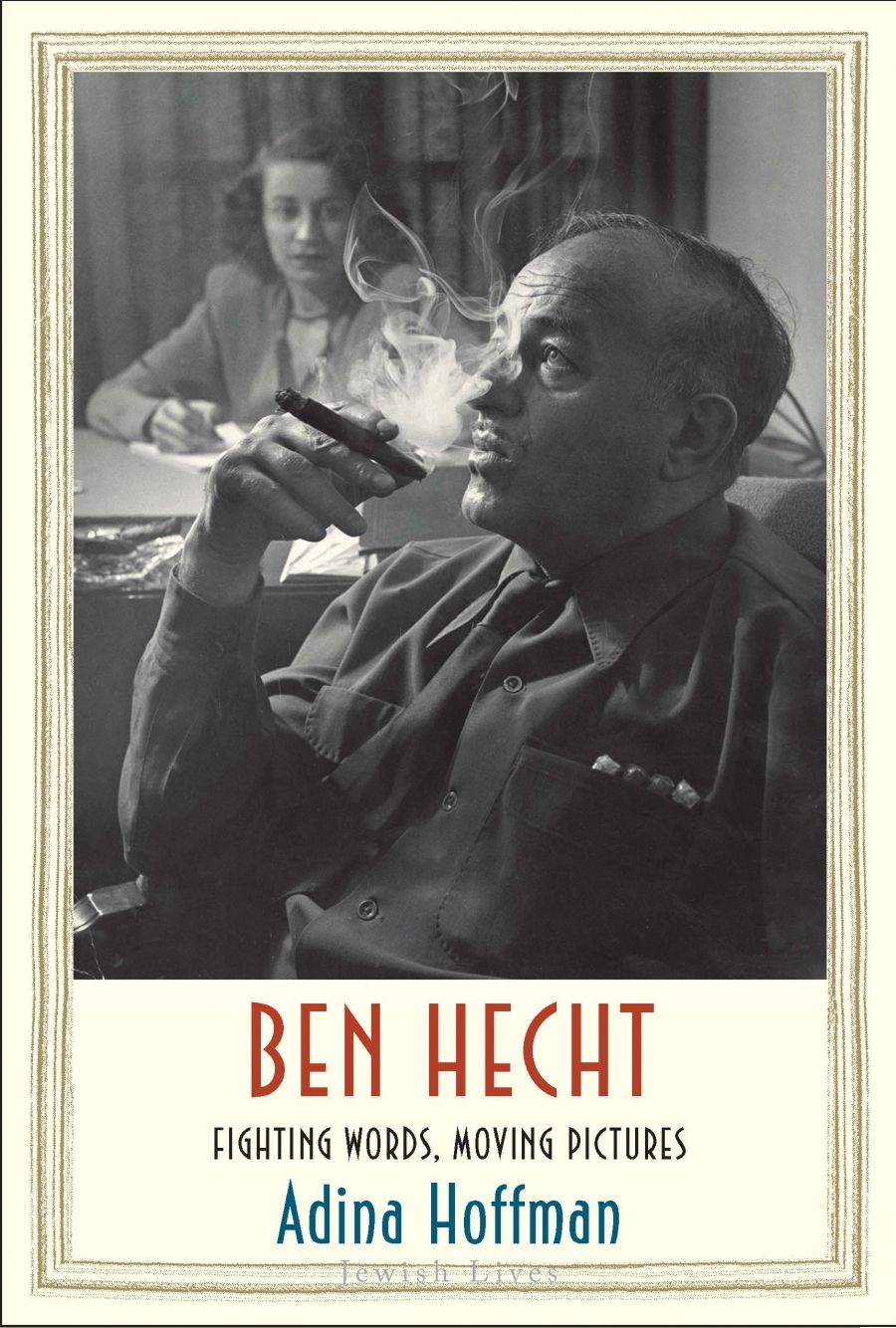

Ben Hecht (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Ben Hecht (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Hoffman’s new biography of Hecht portrays him as a synecdoche of the century, though it is too nuanced to ride that as its explicit thesis. Hoffman – a poet herself – compresses her subject in order to expand it. She shows Hecht detonating verbal explosives amid some of the most consequential fissure points of his age. She generally eschews inspections of his personal intimacies to build a research foundation around his politics, movies, and books.

Hecht the writer came to international renown in the small-magazine culture of interwar modernism, among the likes of Hart Crane, Djuna Barnes, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein. Ezra Pound reported him to be the ‘one intelligent man in the whole United States’ (a rib on his homeland as much as a compliment to Hecht). The impression Hecht made on the international modernist set had been shaped by an apprenticeship in print. The exploits of Chicago’s tenement life had not until the 1920s been the fare of newspapers, but Hecht pioneered a tough-nosed, streetwise reporting style that would fuel his career as a modern novelist, and as a screenwriter who excelled in quick-witted comedies and grimy gangster flicks.

Before the advent of sound, Hecht became one of the first literary luminaries to work for the Hollywood system. Unlike F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner, both of whom notoriously chafed under it, Hecht thrived there, working alongside MacArthur in cigar-smoked sessions punctuated by games of backgammon. Today he is better remembered as a scenarist than a novelist. In 1968, Jean-Luc Godard said of Hecht that he ‘invented 80 percent of what is used in Hollywood movies today’. He was nominated for Best Original Screenplay at the first-ever Academy Awards, and perhaps did more than any other writer to establish the generic architecture of crime film and wordy comedy. But Hoffman deepens the story of Hecht the moviemaker, bringing attention to his role as producer and director, and arguing for his forerunning status in the American independent movement.

Finally, in the realm of politics, Hoffman’s biography is perhaps at its most interesting and complex. Part of Yale University Press’s Jewish Lives series, the book braids the lineaments of literature and film with that of Hecht’s Jewish identity. Catalysed by conflict, Hecht declared that he became a Jew and an American in 1939, an odd statement since he had always been, in some ways, both. Hoffman leaves no question that Hecht became most emboldened by the task of bringing the enormity of extermination camps to the attention of US citizens. Later he became a propagandist for a Jewish state in Palestine. Defined of a piece with his mean-street pugnacity, to be a Jew meant fighting for Jewish lives. With this in mind, Hoffman speculates on the consequences of Hecht’s Zionism more directly than she attends to its historical conditions. Her skills as a writer here compensate for historical limits entailed by biography, as she lets the personality of political actors substitute for a thoroughgoing review of their context. In this she may strike some as overly cautious. From another standpoint, hers is a poetic form of compression that allows the book to whiz along like the man at its heart, to roar by like the Hechtian century that carried him.

Comments powered by CComment