- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

My local shopping centre has seven nail bars, two waxing salons, and a brow bar. A cosmetic surgery clinic touts ‘facial line softening’ and ‘hydra facials’. A laser skin clinic offers cosmetic injections. Three other beauty temples offer ‘cool sculpting’, ‘eyelash perms’, and ‘light therapy’ for skin. I live in a gentrified, working-class suburb in Melbourne’s inner west. I’ve never set foot in these beauty shops, but they’re replicating like cells.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

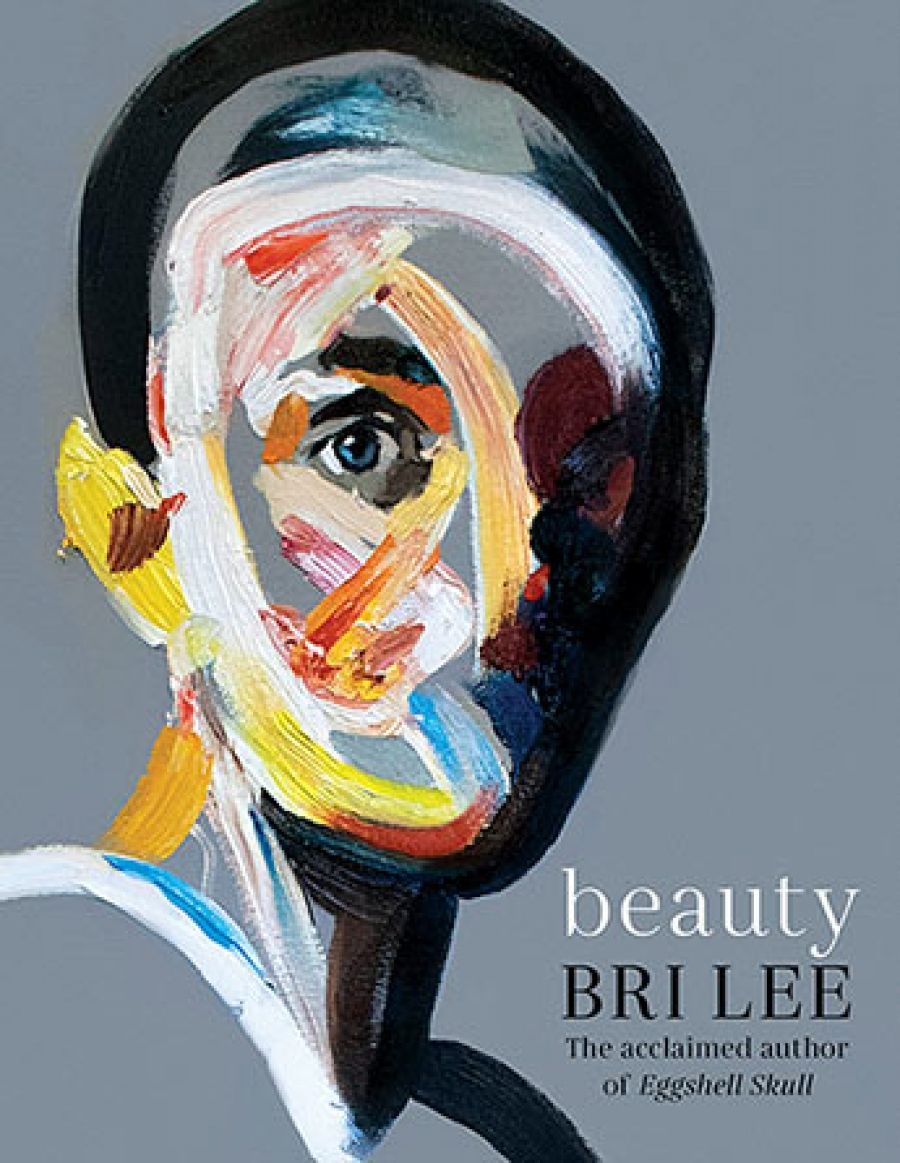

- Book 1 Title: Beauty

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $19.99 pb, 150 pp, 9781760876524

How laughable my optimism seems now, in an age of pouty Instagram influencers and YouTube make-up tutorials. What’s different about today’s beauty industry is that so many women (and quite a few men) are so publicly in thrall to it. No one is forcing people to transmit their cleavages to the world via Instagram or pay surgeons thousands of dollars to rebuild their bottoms. Capitalism has sold the pursuit of the ideal body shape as an ‘empowering’ activity involving endless, costly work. As Bri Lee writes in Beauty, social media’s mass reach enables us to self-police our appearances ‘in perpetuity’.

Lee’s earlier book, Eggshell Skull (2018), was a vivid, brave memoir of her time as a judge’s associate in Queensland, during which she gradually found the courage to press charges against the man who molested her as a child. Eggshell Skull combined observational writing and the confessional mode to make a larger political point about the justice system’s inadequacies and the importance of speaking up. As a court employee, Lee sat through rape trials and saw firsthand how hard it was for a woman to be believed.

Beauty, in contrast, is essay-length and feels like it was written in a hurry. An examination of our oppressive beauty ideals, chiefly told through Lee’s quest to be thinner, the book begins memorably. ‘The house I rented through 2017,’ she writes, ‘was the first place I had ever lived or even stayed in for an extended period of time where I had never thrown up after dinner.’ By 2018 this craving for the ‘small ritual’ of purging her body has returned as she begins a publicity tour for Eggshell Skull. Starving herself, she writes, is a form of control; an outward shaping of the body to conceal inner turmoil.

Beauty is a claustrophobic read. Much of the narrative centres on Lee’s efforts to look good for a glamorous magazine shoot, a portfolio of ‘Visionary Women’. She drinks black coffee, whips herself for eating four squares of chocolate, and receives Instagram updates from a gym called Skinny Bitch Collective. She spends almost $300 on treatments to get rid of pores and acne scars. One day, she eats nothing but two light Cruskits and three mini pieces of sushi. When she hits 61 kilos, she goes shopping for jeans. When she reaches 60.5 she starts smoking again. I was swept along by the elegant prose, marvelling at the horror of it all. Yet I couldn’t help wondering why someone so obviously intelligent, with an oft-mentioned supportive boyfriend, wasn’t getting professional help (or if she was, why it isn’t mentioned in such a self-exposing book).

Lee’s attempts to shape her body are interspersed with her thinking and reading about the sources of self-esteem and the workings of the beauty industry. She reads Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, pondering self-discipline as a source of contentedness. She considers the psychology of fashion: how having a beautiful body has become an ethical ideal. Some of the most interesting observations she quotes are from Will Storr’s 2017 book Selfie. Social media, suggests Storr, has ‘gamified the self’. People are suffering ‘under the torture of the fantasy person they’re failing to become’.

Inevitably, Lee’s ‘Visionary Woman’ shoot does not go to plan. She is thinner, yes, but when the magazine comes out, her portrait is close-cropped. Only her face, hands, and forearms can be seen. The face is a ‘chubby-cheeked, freckle-faced girl’. This picture – and the realisation that such magazines fuel the beauty industry’s oppressive standards while talking of empowerment – is a lightbulb moment for Lee. From here, her narrative moves into more overt social critique. She talks to a young, black woman about the pressures on women of colour to look a particular way, and she discusses The Beauty Myth’s continued relevance. She throws out her scales, celebrates buying size-12 undies at Kmart and vows to relegate beauty to a fun, low-key hobby ‘like my occasional forays into painting’.

Still, I found Beauty a disappointing follow-up to the brilliant, bracing Eggshell Skull. It felt too confessional at times, lacking deeper political analysis or reportage. Changing individual behaviour is admirable, but, as Wolf wrote in 1990, we need political activism – female solidarity – to empower women to turn away from ‘the market’s images’. Australians now spend $1 billion annually on cosmetic procedures alone. (The stakes keep raising: Brazilian butt lifts, body sculpting.) If we collectively ignored the ludicrous ideal bodies presented to us in our feeds, in our magazines, imagine the time and money we could redirect elsewhere.

Comments powered by CComment