- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Innocent Reader, Debra Adelaide’s collection of essays reflecting on the value of reading and the writing life, also works as a memoir. Part I, ‘Reading’, moves from childhood memories of her parents’ Reader’s Digest Condensed Books to discovering J.R.R. Tolkien and other books in the local library, and to the variable guidance of teachers at school and university. Its centrepiece is the powerful essay ‘No Endings No Endings No’, which juxtaposes the shock of discovering that her youngest child has cancer with her grief at the death of Thea Astley in 2004. The last words of Astley’s final novel, Drylands (1999) give this essay its title. Adelaide draws out the hope that they suggest as she tells how reading – aloud to her son in hospital, and to herself when he was too ill to listen – enabled her to survive this terrible time.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

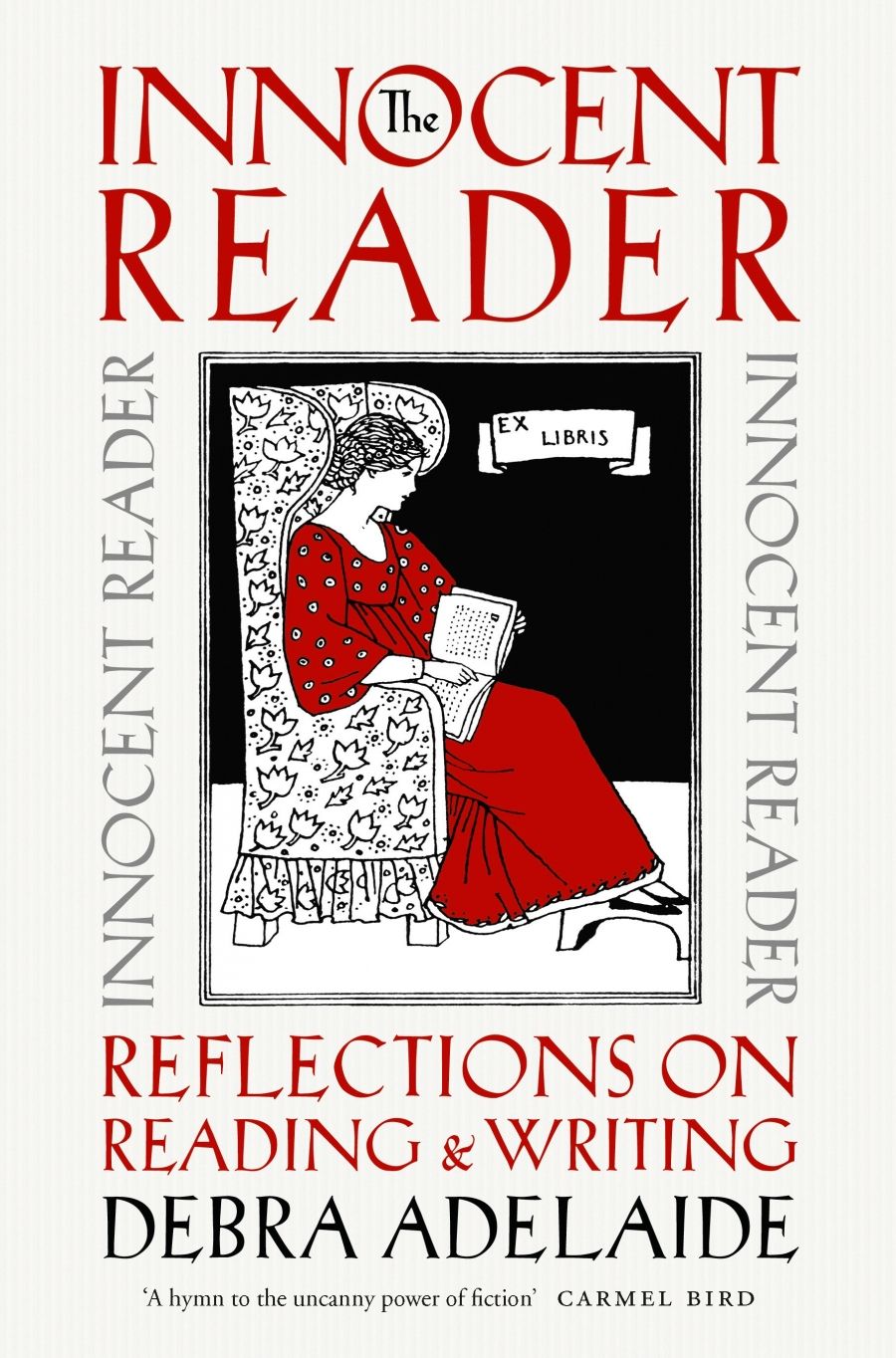

- Book 1 Title: The Innocent Reader

- Book 1 Subtitle: Reflections on reading and writing

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $29.99 pb, 272 pp, 9781760784355

- Book 2 Title: Wild About Books

- Book 2 Subtitle: Essays on books and writing

- Book 2 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $39.95 pb, 202 pp, 9781925801989

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_Meta/December 2019/Wild About Books.jpg

While three of the ‘Reading’ pieces were previously published and exhibit exploratory qualities characteristic of the literary essay, the material in Part II, ‘Writing’, mostly addresses more practical issues, often drawn from Adelaide’s experiences as a teacher of creative writing. She wants her students to realise the importance of learning to read well and of listening attentively, of understanding that ‘a novel is much more than a story’, and that ultimately creative writing is ‘an experiment in failure, a midnight excursion into the dense bush, with neither torch nor map’. Yet her desire as a teacher to emphasise the value of taking risks and even failing is constantly frustrated by an ‘over-regulated and heavily accountable tertiary education system’ where ‘everything that is taught has to be set in stone’.

The third section, ‘Reader + Writer’, contains the title essay, which reclaims readerly innocence not as a blank slate but as a continuing faith in the idea of the ‘intimate conversation’ that exists between writer and reader. The final essay, ‘In Bed with Flaubert’, extends this idea, so that the book becomes a faithful lover, there for you whenever you want it ‘to open up at your desire’. Other essays offer an insider’s perspective on the literary world, drawing on Adelaide’s experiences as a reviewer and a fiction editor. ‘Author/Editor/Reader’ is most informative as well as entertaining, as she tries out various metaphors for the editor’s work – as first reader then as literary backseat driver (or, preferably, as navigator) in the writer’s vehicle. There is an elegiac memoir of her friend and colleague Pat, who was herself a gifted editor; and a marvellous essay, ‘Reading to the Dog’, about how children with reading difficulties can overcome them by reading to a canine friend – just the latest demonstration, she writes, that our relationship with dogs is fundamental to being human.

Michael Wilding’s Wild about Books is also a collection of essays about books and writing, but as a reading experience it could not be more different from The Innocent Reader. Adelaide’s is an artfully structured book, comprising fourteen reflective essays, elegantly presented by Picador with a 1970s art nouveau design. Wilding’s contains dozens of short occasional pieces about books, writing, publishing, and the literary world, apparently arranged in chronological order from the 1980s until the present (there is no information about their original publication). There is, perhaps inevitably, a good deal of repetition, and most pieces are too short to require much readerly engagement.

The longer essays are more interesting: ‘Milton’, for example, evokes Wilding the young lecturer who intrigued undergraduates at Sydney University in 1964 with his vision of Milton as a heroic radical thinker, rather than (as I had expected) a boring old Puritan wanting to justify the ways of God to Man. Wilding’s accounts of how he came to write his three historically based ‘documentaries’ are interesting in themselves, and serve to underline the prodigious range of work that he has written, edited, and published over the past fifty years.

It is a strange experience, as a literary woman of Wilding’s generation, to read a new book in which women are almost completely absent. The population of Wild about Books, from Milton to Marcus Clarke to the Bohemians of the Bulletin to twentieth-century writers of utopian novels or private-eye detective stories and Wilding’s literary colleagues, is male. The only woman writer to get a guernsey on Wilding’s team is the formidable Christina Stead, whose leftist politics and commitment to literary realism earn his praise.Most of the essays are anecdotal, replete with yarns and arcane details about writers. Literary gossip of past and present is sometimes entertaining, but there is a good deal of name-dropping and recycling, and in the latter pieces the paranoia about surveillance, internet and other digital censorship, and political correctness becomes tedious. That’s a pity, because Wilding can be very funny indeed when he’s writing fiction, including fiction driven by those very obsessions, as with his novel Academia Nuts (2002).

A number of essays in Wild about Books rightly rage against ‘the purge of our libraries’, especially the Fisher Library at Sydney University, where Wilding taught for many years. At Fisher, it used to be possible for a researcher to roam the stacks at will. Now, like most university libraries, it has shed so many of its reference books and relegated so many ‘old’ books to off-site locations that such pleasures are no longer available, and indeed the loss of actual books invites accusations of censorship such as he makes.

This lament for lost libraries brings to mind the quotation from Ali Smith’s Public Library and Other Stories (2015): ‘Because libraries have always been a part of any civilization they are not negotiable. They are part of our inheritance.’ And Adelaide’s emphasis on the vital importance of books in our lives recalls Beejay Silcox’s urgent questions, at the end of her review of Syria’s Secret Library in the October 2019 issue of ABR: ‘As libraries around the country wither and close, literary opportunities shrink, and arts funding is razed: What hard work are we willing to do? What risks are we willing to take?’

Comments powered by CComment