- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Serotonin is Michel Houellebecq’s eighth novel and appears four years after the scandalous and critically successful Submission (2015), a dystopian novel that depicts France under sharia law. In Serotonin, we are again presented with the standard Houellebecquian narrator: white, middle-aged, and middle class, seemingly in the throes of some mid-life crisis of a predominantly – but not exclusively – sexual nature.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

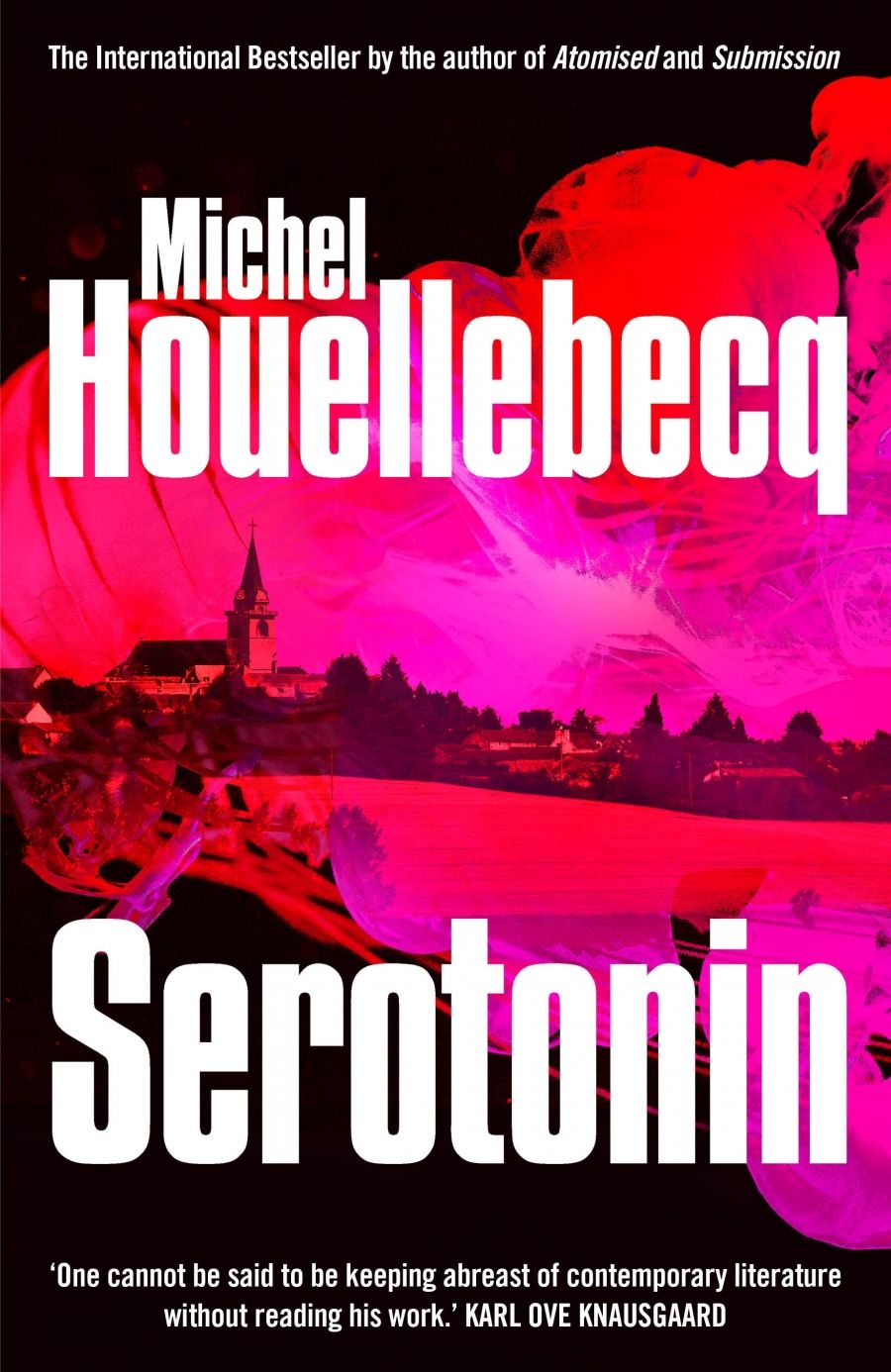

- Book 1 Title: Serotonin

- Book 1 Biblio: William Heinemann, $32 pb, 309 pp, 9781785152245

Despite the graphic descriptions one is used to in a Houellebecq novel, Serotonin is less about sex than love, or precisely its impossibility: failed love, lost love, doomed love. Houellebecq’s narrators tend to blame society for their inability to love (Labrouste calls society ‘a machine for destroying love’) when clearly these men are simply, and by their own admission, not up to the task. Houellebecq has always been an outspoken critic of the concept of free will, but in Serotonin this is starting to sound like a cop-out. Musing on the opportunity to make a life together with a former lover, Labrouste concludes that life ‘had decided otherwise’. There is redemption of sorts in the form of an oddly Christian epiphany, but it comes too late for Labrouste. There are other things besides love at stake in the novel, which also grapples somewhat half-heartedly with ‘bigger issues’ such as the climate crisis, GM foods, the rights of farmers and animals, and the devastating effects of free trade on national industries.

Houellebecq is on to a good thing: malaise sells, which says more about late capitalism than about his novels. He also discovered a formula for the contemporary novel that he reiterates in Serotonin: ‘let’s get back to my subject which is me, not that it’s especially interesting, but it’s my subject’. This is an approach Houellebecq assumed in his first novel, Whatever (1994), which the narrator describes as ‘a succession of anecdotes in which I am the hero’. This proved a bankable formula for Houellebecq, held together by vague and shifting narrative frameworks. Whatever worked for two reasons: these anecdotes were interspersed with commentary on aspects of everyday life of interest to the late-capitalist reader (ATMs, paying bills, buying a bed); and it was a short novel (just over 100 pages). Serotonin is not only long, but the narrator is scarcely relatable and there are fewer of the pithy insights Houellebecq is known for. There is humour, but it is largely overwhelmed by the more unpleasant aspects of the narrator’s personality. Serotonin is Houellebecq stripped back, a kind of take-me-or-leave-me with little narrative subterfuge or essayistic digression. Even the episode of the farmers’ revolt, said to have presaged the Gilets jaunes movement and primarily what the novel is celebrated for, is just that: an episode.

Labrouste’s world view is a tired one. No doubt Houellebecq is tired too. The question is, do we care? Do we care about a narrator whose most successful act consists of contaminating the recycling bins of his apartment building with rubbish and food scraps? We don’t have to care for a book or its themes for it to be a good book – but it helps. What does Serotonin offer but the all-too-familiar Houellebecquian utopia where romance and pornography are combined in equal parts? Labrouste appears much older than forty-six, prompting one to speculate that this book is the musings of a man in his sixties, much like Houellebecq himself. Labrouste inhabits a dated binary world where men are from Mars and women from Venus and alternate sexualities are dismissed as ‘faggot’ and ‘queer’.

So just who is Houellebecq writing for? I am reminded of Gertrude Stein’s answer: ‘for myself and strangers’, presumably in this order. Yet he is read, largely because his reputation precedes him. Like all Houellebecq novels following Atomised (1998), Serotonin was an instant bestseller. Sure, one gets it: these are not the views of the author, it is a satirical portrait of men like Labrouste whom Houellebecq supposes to be typical. Towards the end of the book, however, I experienced something I haven’t experienced before with a Houellebecq novel: the desire to skip pages; not so much to find out what happens, but because I simply lost interest in Florent-Claude Labrouste, his troubles, his reveries, his observations. The paradox Serotonin presents is that we are just not that interested in other peoples’ problems; we have enough of our own. The irony is that Labrouste – and indeed Houellebecq – would probably agree.

Comments powered by CComment