- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In their earliest incarnations, fairy tales are gruesome stories riddled with murder, cannibalism, and mutilation. Written in early seventeenth-century Italy, Giambattista Basile’s Cinderella snaps her stepmother’s neck with the lid of a trunk. This motif reappears in the nineteenth-century German ‘The Juniper Tree’, but this time the stepmother wields the trunk lid, decapitating her husband’s young son. In seventeenth-century France, Charles Perrault’s Bluebeard kills his many wives because of their curiosity, while in his adaptation of ‘Sleeping Beauty’, the Queen’s appetite for eating children drives her to commit suicide out of shame. Jealous, Snow White’s stepmother (and in some versions her biological mother) wants to kill the girl and eat her innards, but is ultimately thwarted; her punishment is to dance herself to death wearing red-hot iron shoes.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

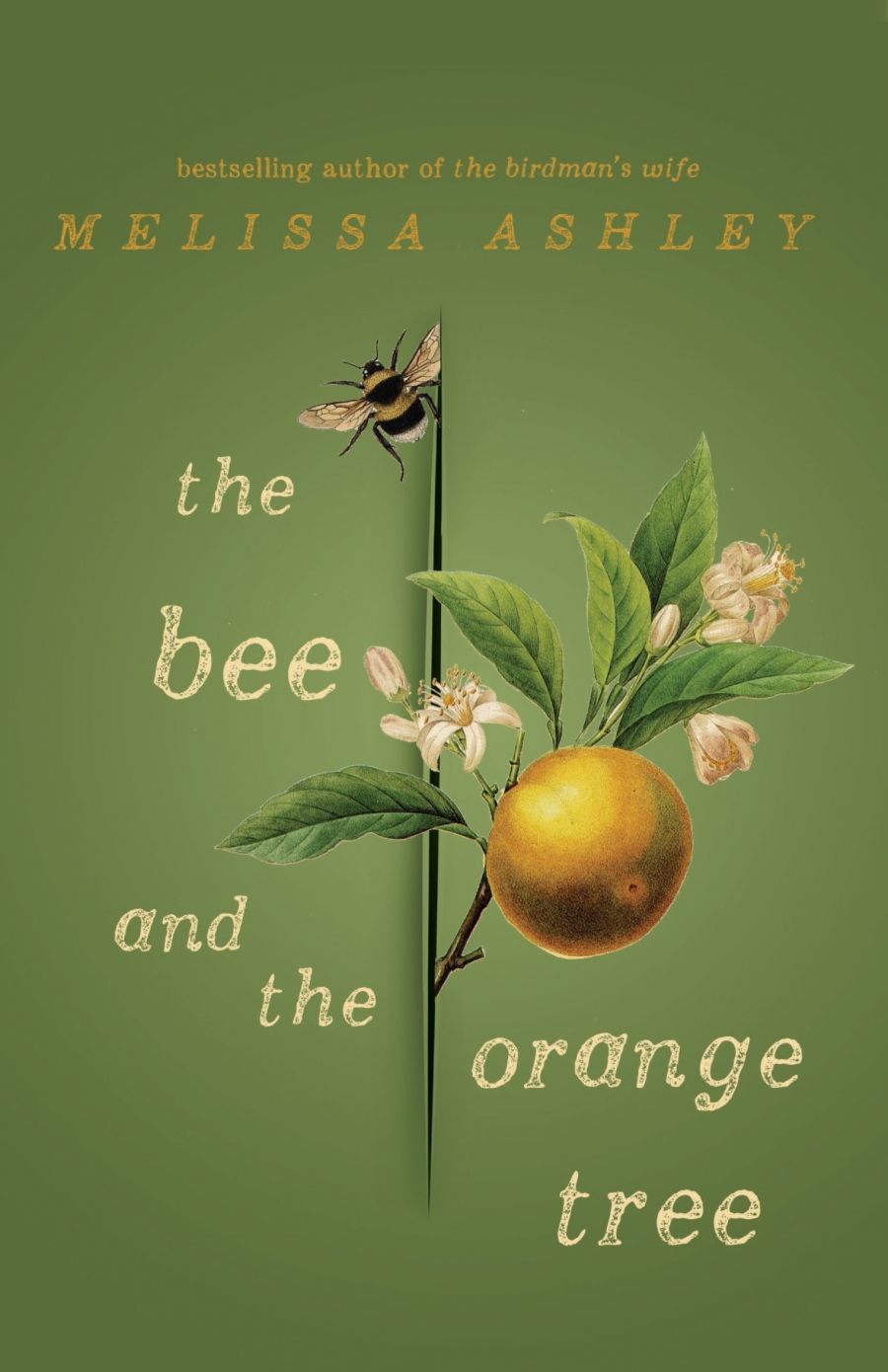

- Book 1 Title: The Bee and the Orange Tree

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press, $35 hb, 384 pp, 9781925712018

Traditionally, these and countless other classic fairy stories have been read as cautionary tales. Ostensibly aimed at keeping children in line, their morals more pointedly reflect the cultural norms and anxieties of the times in which they were recorded – fears often made manifest in the restriction of women’s social and sexual lives. That so many of these narratives depict maids locked in towers, duplicitous brides, sinister crones, and ‘difficult’ women (to name but a few recurring images) has been the subject of much revisionist feminist scholarship in recent decades. Numerous fictional retellings, perhaps most famously Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber (1979), have reinvented, challenged, and subverted these tropes.

Melissa Ashley (photograph by David Merrylees)

Melissa Ashley (photograph by David Merrylees)

A follow-up to her award-winning first novel, The Birdman’s Wife (2016), Melissa Ashley’s The Bee and the Orange Tree continues the important trend of interrogating fairy tales, their motifs and many authors, and the social and intellectual worlds that shaped them. Promoted as the ‘untold story of the woman who invented fairy tales’, Baroness Madame Marie Catherine d’Aulnoy, this work of historical fiction is much more complex than its somewhat misleading tagline indicates. Splitting its focus between three female characters – the celebrated conteuse, Marie Catherine; her daughter Angelina, a once-cloistered young woman, now an emerging writer in her own right; and Nicola Tiquet, an extremely wealthy but oppressed socialite whose future is uncertain – this novel uses fairy tales to delve into ideas about writers, the writing process, and the horrific realities of women’s lives in the stifling patriarchy of seventeenth-century France.

For much of the book, Marie Catherine, a once-prolific storyteller, suffers from writer’s block. Her inability to create new tales at a moment when contes des fées are in literary vogue is not only poignantly portrayed, but it also underscores the scant opportunities women have to improve their situations or to escape the status quo. Though hardly a pauper, Marie Catherine, without the income her writing brings, is effectively rendered mute in a world that speaks the language of money. Clear parallels are drawn between the female characters in her fairy tales (snippets of which are woven in the novel) and those in Marie Catherine’s immediate circle of friends and family. ‘I was those women,’ Angelina observes, recalling the many years she spent isolated in a convent, ‘I felt what they felt, every word of it.’ Tiquet’s imprisonment for an alleged attack on her husband dramatises many of the grotesque ways in which women are treated in fairy tales and in this historical period. ‘Her attempt to improve her circumstances had come to naught … She could not tell if the harshest beatings had already been carried out or if they lay in wait.’

Literary salons situate Marie Catherine as the once and future queen of fairy-tale authors in The Bee and the Orange Tree, offering lively vignettes of Parisian literati in the late 1600s that feature several notable authors, such as Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de La Force (whose life and Rapunzel tale are reimagined in Kate Forsyth’s Bitter Greens, 2013), Henriette-Julie de Murat, Perrault, and Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier de Villandon, all mingling with established and aspiring raconteurs. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are frequent discussions in this book about the nuances of craft and the joys and difficulties of writing; they are delightfully timeless. Likewise, Marie Catherine’s often frustrating interactions with her Dutch publisher will be achingly familiar to creative artists negotiating today’s market-driven industry.

[H]e had heard the fairy tales of Charles Perrault were most edifying for young ladies … maybe she could imitate Perrault’s style of closing each story with a morality poem, six lines of verse in which the theme of the story was distilled, along with a warning to the reader on how to avoid a similar plight? What did she think of that idea? There was perhaps a market opening for children’s tales across the Channel … Had she heard of Mother Goose?

These scenes underscore one of the novel’s strongest themes: the subversive power of women’s writing. ‘An author must be brave,’ said Marie Catherine. ‘You can say whatever you like in your writing. It’s your opportunity to reimagine the world as you would have it in turn.’ The Bee and the Orange Tree does just that. Without anachronism, it offers women writers as much power as is credible in their historical context, giving their revolutionary ideas a voice and an audience. In the end, Marie Catherine reflects, ‘[p]erhaps the visions in her fairy worlds did not match the lives of the women around her, but at least, with her pen, she could have her say’, and in so doing, inspire change.

Comments powered by CComment