- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The recent death of Les Murray can be likened in its significance to the passing of Victor Hugo, after which, as Stéphane Mallarmé famously wrote, poetry ‘could fly off, freely scattering its numberless and irreducible elements’. Murray’s subsumption of the Australian nationalist tradition in poetry, including The Bulletin schools of both the 1890s (A.G. Stephens) and 1940s (Douglas Stewart), has delineated an influential pathway in our literature for more than fifty years. Yet the death in 2017 of the American poet John Ashbery might be viewed as equivalent in its effect, given the impact of his work on several generations of local poets, which has in many respects constituted a counter-stream to Murray’s often narrowly defined nationalism. Ashbery’s voice has been infectiously dominant in English-language poetries over several decades, in a manner similar to T.S. Eliot’s impression on poets of the earlier twentieth century. Critic Susan Schultz, the publisher of this volume, has charted the dynamics of its transcultural influence in her aptly titled collection, The Tribe of John (1995)

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

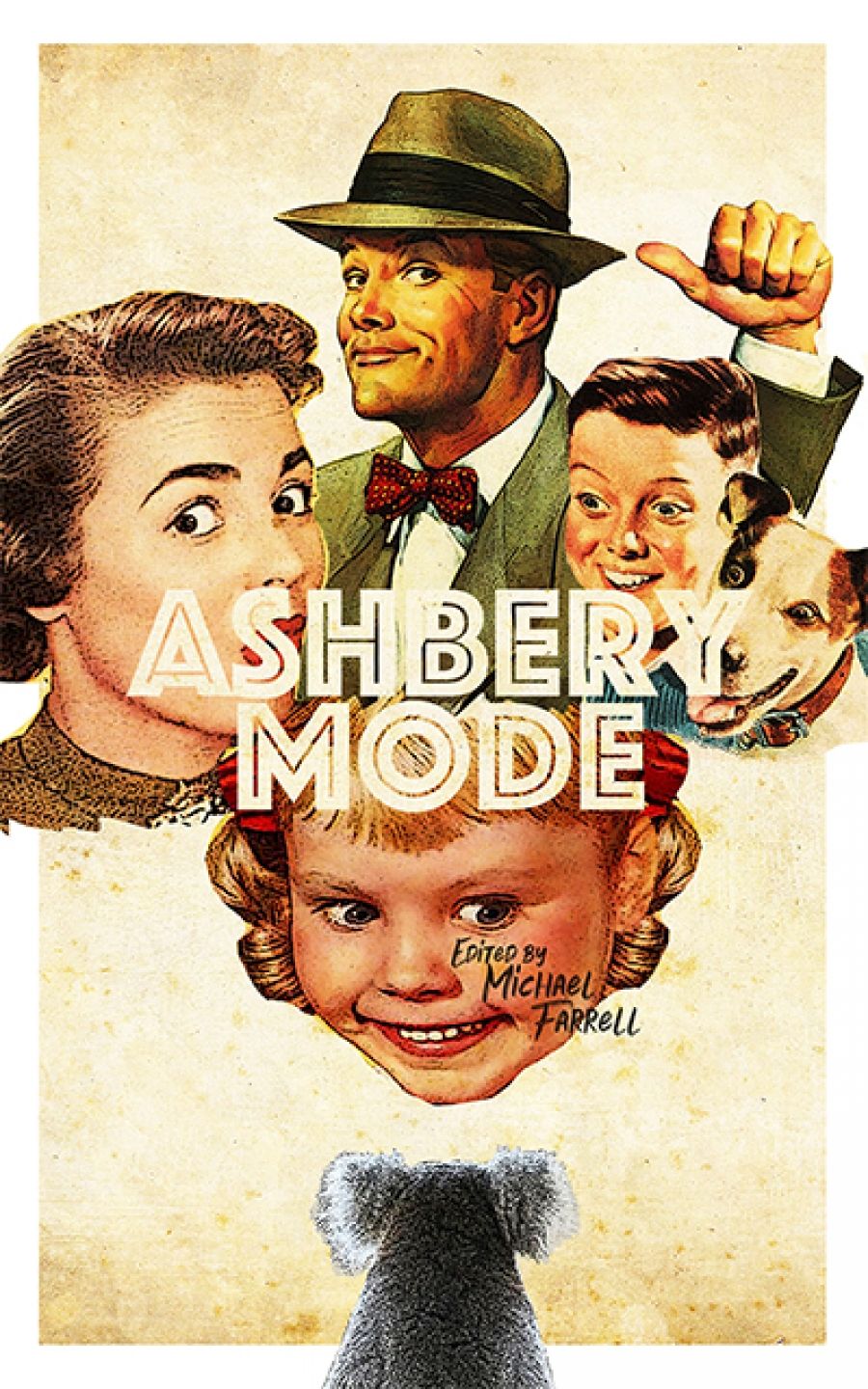

- Book 1 Title: Ashbery Mode

- Book 1 Biblio: Tinfish Press, US$20 pb, 126 pp, 9781732928602

But Ashbery’s connections to Australian poetry, especially in its reception of modernist stylistic approaches, are more particular. It is an association that commences with his purchase of The Darkening Ecliptic by notorious hoax-poet ‘Ern Malley’ in a Gotham bookshop in the 1940s, after which Malley apparently became one of his favourite poets. The Malley poems were then included by Ashbery in a special ‘Collaborations’ issue of the journal Locus Solus in 1961, alongside seminal avant-garde texts by Breton, Soupault, Marinetti, and William S. Burroughs. If Ashbery’s style is characterised by its incorporation of French modernist sources – cubist juxtapositions and surrealist conjunctions, as well as a tendency to humour – then ‘Ern Malley’ is the local poet who fits the bill.

Australian poetry during the postwar period precisely defined itself by its rejection of the Malley example. Unremittingly serious and determinedly anti-modernist, poets like Judith Wright set themselves the task of finding symbolic correlatives for white Australian experience in a traditional mode. The fulcrum for a renewed reception of modernist poetics was Donald M. Allen’s The New American Poetry, published in 1960 though banned here for several years. It was through this American model that Australians approached the (mainly untranslated) techniques of avant-garde modernist practice. While Allen’s anthology offered a wide survey of ‘postmodern’ examples, Ashbery and related New York School poets were particularly valuable in connecting local practitioners with prior European experiments in collage, proceduralism, and surrealist imagery.

American poet John Ashbery, 1975 (photograph by Michael Teague/Wikimedia Commons)

American poet John Ashbery, 1975 (photograph by Michael Teague/Wikimedia Commons)

Ashbery’s early volumes were being circulated among Melbourne poets like Ken Taylor by the late 1960s; however, the principal conduit for his influence was Sydney poet John E. Tranter (the ‘E’ stands for ‘Ernest’, as in Malley, of whom he was also an enthusiast). Tranter’s looping, discursive style of the 1970s, marked by collage-like disjunctions, directly adapts the Ashbery mode to urban Australian experience. It was Tranter who acted as celebrant for Ashbery’s highly successful 1992 reading tour (recollected here in a poem by David Prater), where the American performed to packed halls in Sydney and Melbourne. And Tranter’s online journal, Jacket, launched in 1997, established itself as an essential resource for a globalising poetics in the digital era, with a markedly New York School emphasis: this deliberate internationalism repudiates the nationalist concerns inherited by Murray.

Michael Farrell’s commemorative anthology of recent homages to Ashbery, mostly collected from the past decade, demonstrates how this influence now spans several generations. It is notable that some of the liveliest poems in the volume are from its youngest contributors, Andrew Mahony and Oscar Schwartz, written while both were in their early twenties. The collection also demonstrates how the range of Ashbery’s writing, as it moves through distinct periods – from the lyricism of Some Trees (1956), through the expansive meditations of his celebrated middle period, to his quirkily Rimbaudian later style – cannot be restricted to a singular approach.

Tranter, for example, is represented here not by his most explicit tribute poem, ‘The Anaglyph’, a composition which utilises the terminal words of Ashbery’s ‘Clepsydra’ to create its own commentary on anxieties of influence. Instead, we have the challenging ‘Electrical Disturbance’, which draws on Ashbery’s experiments with procedural techniques in The Tennis Court Oath (1962): in this case, the poem transmutes an interview Tranter conducted with Ashbery through speech-to-text computer manipulations, with startling if rarified results.

This experimental approach has been incorporated within the longstanding practice of many poets here, including veteran figures such as Javant Biarujia, Chris Edwards, Hazel Smith, and Ruark Lewis. They have been joined more recently by a younger generation. For post-Jacket poets of the internet age, such as Tamryn Bennett, A.J. Carruthers, Bella Li, and Toby Fitch, these procedural techniques can now be taken for granted. Their work stands alongside established poets, such as Gig Ryan and Peter Rose, for whom the Ashbery mode has been thoroughly incorporated within a distinctive and fully developed personal voice. The modernist aesthetic of collage and disjunction, which had so incensed the perpetrators of the ‘Ern Malley’ hoax that they provided excellent examples of their own, is now accepted and absorbed within the practice of contemporary Australian poetry: this specialised anthology is a handy representation of its currency and scope.

Comments powered by CComment