- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At first glance, the premise of this book seems dubious. Katharine Smyth, an American woman in her mid-twenties, turns to the life and work of Virginia Woolf for solace after the death of her father. There is no doubt that Woolf writes brilliantly about death, particularly in the novel Smyth focuses on, To the Lighthouse (1927), which fictionalises the death of Woolf’s mother, Julia Stephen. But what comfort could Smyth hope to find in the work of a writer who herself refuses any of the usual consolations? After losing her mother and her elder half-sister, Stella, in her early teens, and then her father, Leslie, and her elder brother, Thoby, in her twenties, Woolf knew that there was no solace to be found. Her only comfort was that at least ‘the gods (as I used to phrase it) were taking one seriously’.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

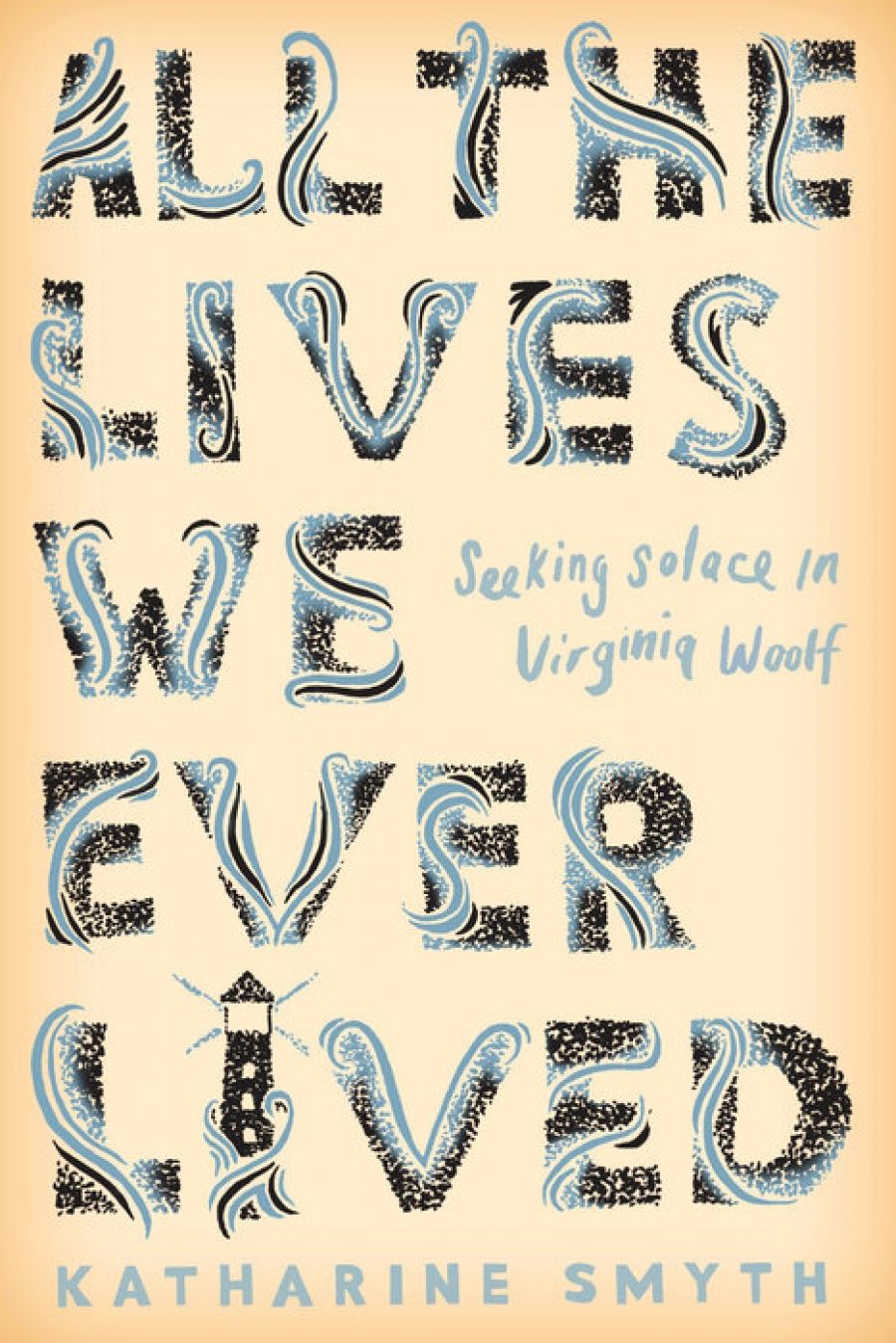

- Book 1 Title: All the Lives We Ever Lived

- Book 1 Subtitle: Seeking solace in Virginia Woolf

- Book 1 Biblio: Atlantic Books, $32.99 hb, 320 pp, 9781786492852

Smyth, to her credit, is not seeking to turn Woolf into some kind of self-help grief guru. The novelist’s cool and unflinching acknowledgment of death’s dominion is what attracts Smyth. She explains that when she first read To the Lighthouse, she was appalled by Mrs Ramsay’s sudden death in Part II. Mrs Ramsay had seemed to be the central character, the woman at the heart of the richly realised, late-Victorian family that, in Part I, is holidaying on the Isle of Skye. How could she be dispensed with so simply? Smyth was horrified not just by the fact of Mrs Ramsay’s death but by the way it was portrayed – in ‘detached and oddly graceless language, trapped between the bars of a parenthetical aside’. Yet even as a twenty-year-old, she was aware that ‘it was life’s cruel trick and not Woolf’s own’. Rather than being repelled by this supremely reader-unfriendly section of Woolf’s novel, she was drawn in more deeply.

Photograph of Virginia Woolf, 1927 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Photograph of Virginia Woolf, 1927 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Smyth’s world is almost entirely unlike that of Woolf and To the Lighthouse. She grew up in Boston, the only child of architect parents, one English, one Australian. She was not yet in her teens when her father was first diagnosed with cancer, and his long dying cast a shadow over her youth and young womanhood. She adored him, but she is unsparing in her analysis of his life and character. He was full of a potential he was never able to realise; his alcoholism was part of a larger surrender to fate, a refusal to fight, a refusal to care. Yet he was, for Smyth, the magical parent, her own Mrs Ramsay, enchanting the space of childhood, showing a ‘deference’ to his daughter’s ‘vision’ that helped bring her into the world.

Structurally, this would make Smyth’s mother, Minty, the equivalent of Mr Ramsay, but Smyth is quick to assert that Minty is nothing like Mrs Ramsay’s needful and difficult husband. Minty is a troubling presence in this book, a character with virtually no emotional weight. Given Woolf’s preoccupation with mothers both literal and metaphorical, it seems odd that a book inspired by her should be so in thrall to the paternal. What matters to Smyth, as she interweaves the story of her father’s life and death with that of her own encounters with Woolf’s life and work, is not the correspondence between her life and Woolf’s but the way Woolf deals with grief. Woolf does not seek to either mitigate or exaggerate it, to pretend it is not there or to pretend it is everything. ‘To want and not to have,’ muses Lily Briscoe in Part III of To the Lighthouse. ‘And then to want and not to have – to want and want – how that wrung the heart, and wrung it again and again! Oh, Mrs Ramsay!’ The cry is wrenched from her in a moment of utter anguish. Sheer unassuageable need brings her to her knees. ‘To want and want and not to have – my god, the primal, powerful injustice of that phrase!’ Smyth comments. ‘And the terrible simplicity of the problem, insoluble, that death presents us with.’

For Smyth, there is solace – of a grim kind, certainly – in the confirmation that solace is impossible. She takes a perverse comfort in Woolf’s affirmation of the intractability of loss. In To the Lighthouse, Woolf proposes that through art we may learn to live with this knowledge. In the third part of the novel, her artist–figure, Lily, works on a picture of Mrs Ramsay as she stands on the lawn of the Ramsays’ summer house. The rhythm of her brush strokes becomes the rhythm of the waves, the rhythm of her thoughts and murmured words, the rhythm of the lighthouse beam across the bay. As the painting finds its form, Mrs Ramsay’s intolerable absence becomes fleeting presence.

Smyth herself writes with the idea of creating a ‘perfect portrait’ of her father, one that will magically ‘raise him from the dead’. Unlike Mrs Ramsay, Smyth’s father does not appear. Even Smyth remains a shadowy figure. Does she have a job? Does she have friends, lovers, children? Where does she live, and on what? She never tells us. She exists solely as a grieving daughter – and as a reader of Virginia Woolf. In this latter capacity, she is at her best. In her hands, To the Lighthouse unfolds and unfolds; the distance between Woolf’s world and our own comes to seem no more than a step.

Comments powered by CComment