- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

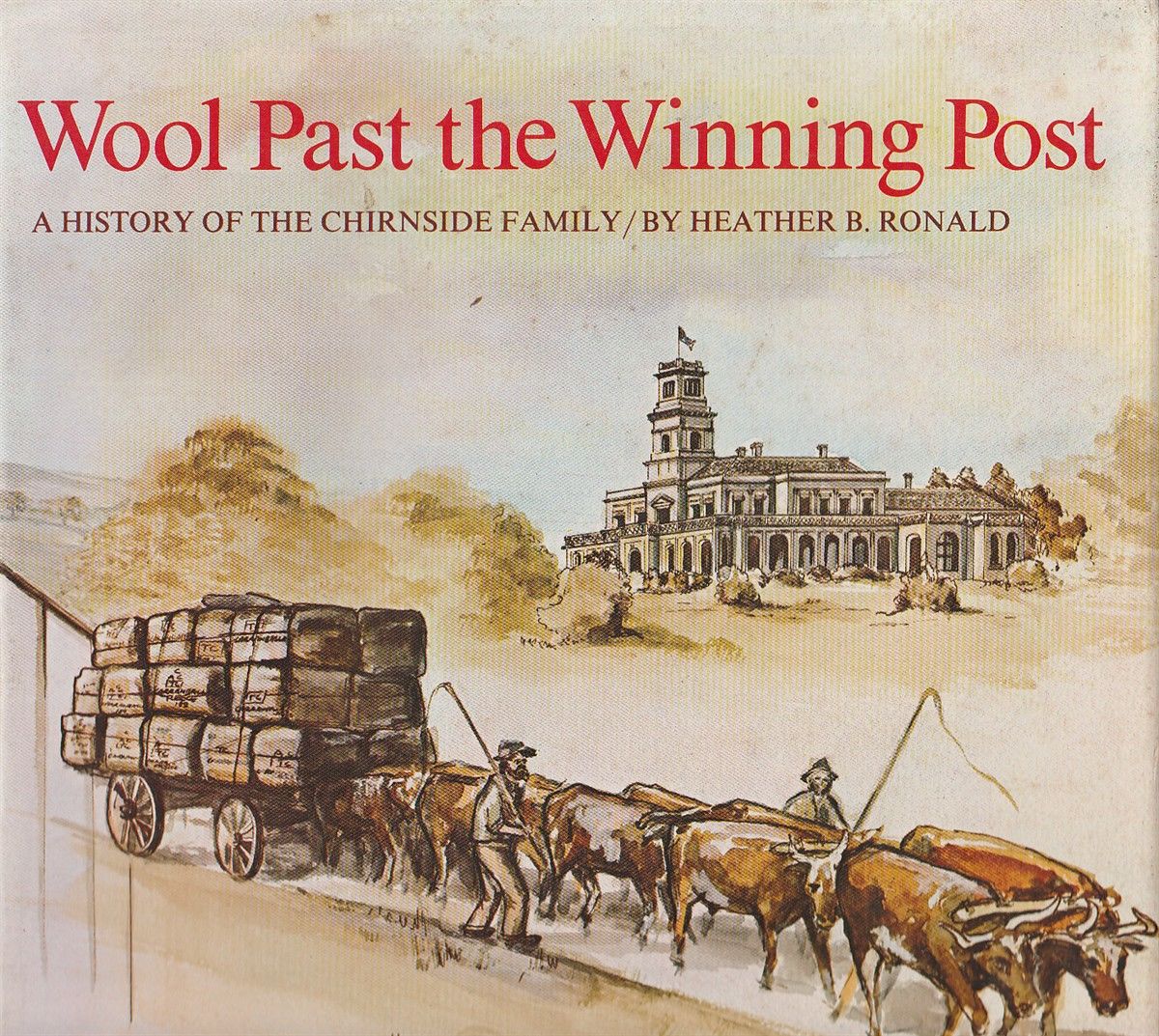

- Article Title: Wool Past the Winning Post

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For many Victorians their impressions of the squatting age have been formed by visits to Como or to Werribee Park. These mansions, of course, reflect the ultimate achievement of the squatters’ aspirations but tell us little of the struggles involved in realising those aspirations. These tangible proofs of squatter opulence, coupled with historical accounts of the squatter-selector battles, have inevitably cast the squatters in the role of the ‘bad guy.’ But to Heather Ronald her squatters, the Chirnsides, are the ‘good guys.’ ‘I dispute the oft-repeated statement,’ she says, ‘that squatters set themselves up as a class above everyone else … Many of the earliest successful squatters came from good families and were educated people; their attitudes were moulded by the way of life in rural Scotland, with its Squire and tenant system … Thomas and Andrew, in their estate management, were only following the example set by good landlords at home.’ But this was precisely why many Australians opposed them.

- Book 1 Title: Wool Past the Winning Post

- Book 1 Biblio: Landvale Enterprises, $16.95 hb, 203 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Heather Ronald is the great-granddaughter Andrew Chirnside so it is not surprising that she should see her forbears in a favourable light. Not that she is unaware of their shortcomings for she makes no attempt to play down the weaknesses of character or to conceal family quarrels. But her sympathies lie with the squatter rather than with selectors, shearers or land-taxers.

The story she tells is not quite a rags-to-riches one but close to it. Thomas and Andrew Chirnside, the youngest sons of a Scottish tenant farmer of 315 acres in Victoria, by the 1870s owned or leased half a million acres in Victoria, plus further extensive holdings in New South Wales and Queensland. They built substantial houses on their runs, culminating in the mansion Werribee Park. When they returned to Scotland temporarily in 1886, they were able to buy Skibo Castle and its 20,000 acres £125,000. When Thomas died in 1887, he left an estate valued at £150,000; Andrew died three years later leaving an estate of £302,095. In both cases the amounts would have been greater had not the brothers avoided death duties by dividing their properties among members of the family. For the brothers founded a dynasty in Victoria, bringing out brothers, cousins and nephews to manage their runs.

The Chirnside story is typical of the squatting experience: the buying of freehold land in the 1850s, exploiting the selection acts in the 1860s, expanding into New South Wales and Queensland in the 1870s. Shearing a million sheep, they were able to finance these activities, entertain lavishly and donate money to worthy causes generously. The re-creation of the life they had left in Scotland was complete when they leased parts of their property to tenant farmers. They turned the clock back even further to the feudal system when they financed and trained the Werribee Detachment of the Horse Artillery. But, from the evidence presented, they do seem to have been well-intentioned landlords anxious to see their land put to good use and to be respected by their tenants.

But success was not unalloyed. Thomas died by his own hand, a somewhat pathetic figure. The next generation did not possess the same qualities as the pioneer brothers. The two sons feuded over the division of Werribee Park.

How was their success achieved? Partly by serendipity, largely by the personal qualities of the two brothers. Heather Ronald attributes success to strong family ties and Calvinistic upbringing: ‘Brought up never to be idle, to work-with all his might, to keep the Sabbath day Holy, he (Thomas) believed that virtue would be rewarded by riches.’ Thomas, who arrived in Sydney in 1839, seems to have been the driving force, the decision maker who rarely decided wrongly. Except perhaps in affairs·of the heart.

He had unsuccessfully wooed Mary Begbie, his cousin, on a visit home in 1847. When Andrew returned to Scotland shortly after, Thomas told him to bring Mary back, either to marry him or as his wife. Mary chose Andrew, but Thomas seems to have retained his affection for her, building Werribee Park from a desire ‘to place Mary in a setting unequalled outside Government House.’

Heather Ronald has obviously researched her topic thoroughly, as the bibliography indicates, but there are times when one wishes she had footnoted her sources. Her book covers not only the pioneer brothers but their descendants and relatives, tracing their story down to the present. Sometimes the detail of family relationships becomes tedious and confusing but there is a complete family tree to help sort this out. The book is well illustrated and overall presents an intriguing view of a way of life that has vanished.

Comments powered by CComment