- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter Collections

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A journal of a life

- Article Subtitle: Audrey Tennyson's illuminating letters

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Audrey Tennyson, in a letter to her mother in January 1903, wrote: ‘About my letters … would you ask somebody to buy at Harrods a japanned tin box for holding them … the great thing is to keep them together as if they are in several places they are likely to get put away and forgotten. I am afraid they won’t be worth publishing but they may be of great interest to the boys some day – and Hallam might perhaps make use of them for a book on Australia.

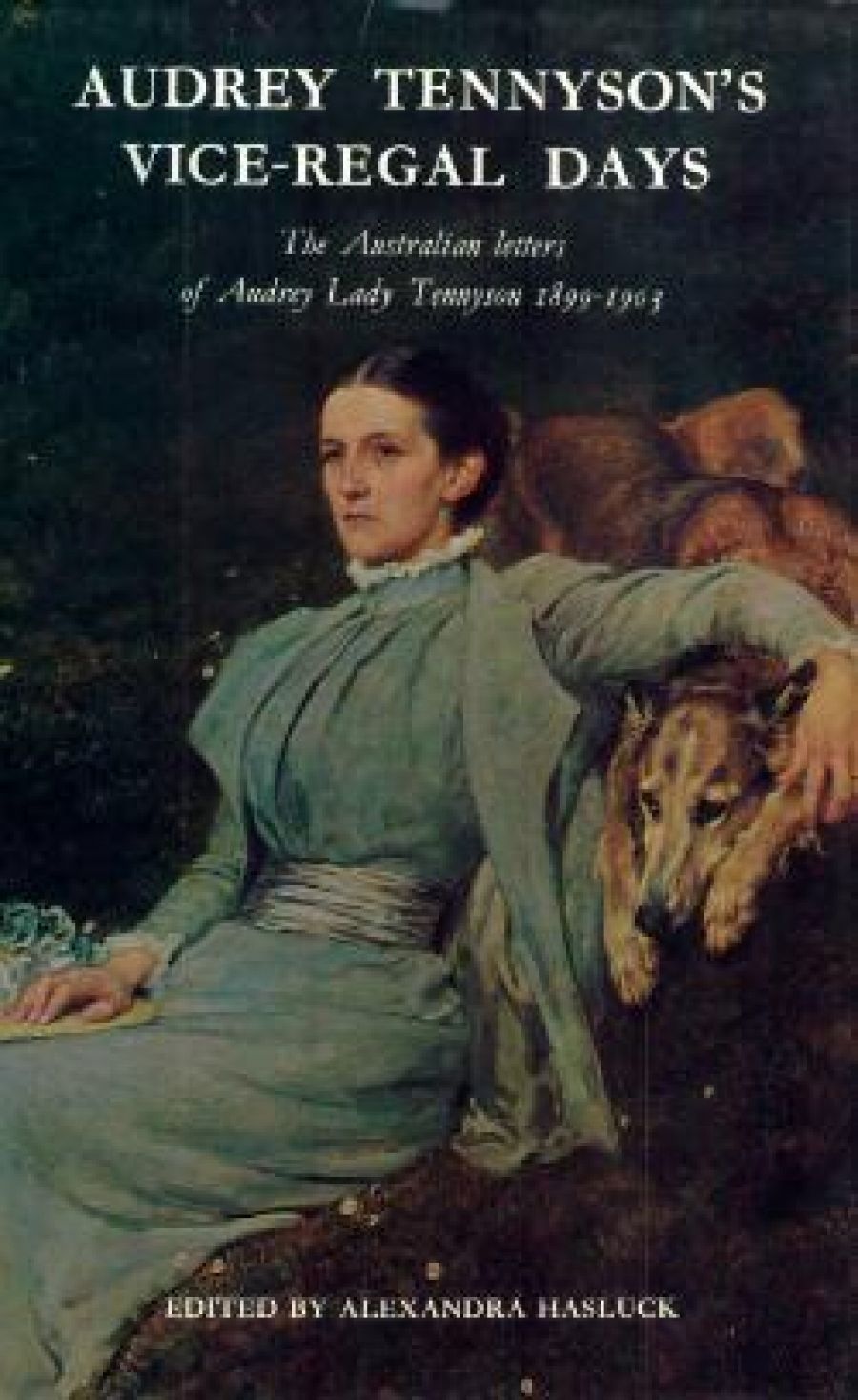

- Book 1 Title: Audrey Tennyson's Vice-Regal Days

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $18.50 hb, 361 pp

Lady Tennyson was not only, as it turns out, a prolific correspondent (she wrote all told 262 letters to her mother, some running to 60 or more foolscap sheets in length); she has left behind her a most important document of Australian history, and especially, a very human story – a classic picture of a cultured and sensitive Englishwoman ‘reacting to a colonial people and its society’. And I find this most fascinating of all.

Her letters display not only her devotion to her husband and her pride in his achievements (in the Governor-Generalship, she wrote, he held ‘one of the greatest positions England had to offer’, and she recalled with pride how the proprietor of the Melbourne Argus had said that ‘Hallam had done more than anybody else in making peace between the States and the Commonwealth’), but the eager and observant eye she cast on her new environment and the literate and intelligent manner in which she recorded her impressions. It is not surprising I suppose, since earlier in her marriage she had acted as secretary and scribe, as it were, to her illustrious father-in-law, the Poet Laureate.

She saw Australian society and its mores objectively and dispassionately. She noted the social climbing of the ‘upper ten’ in Adelaide; the obsession with full titles, ‘the Honble, the Right Honble etc.’ One gentleman, indeed, would not advance in, the reception line until he was addressed as ‘Mr So-and-So, the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages.’ Girls, she observed, looked pretty at a distance, but when they came near ‘they invariably have shocking complexions, bad teeth and dreadful voices, with more or less Australian twangs.’ Australians ‘are a most greedy people and spend most of their income on food.’ They ‘eat like ogres’, she recorded elsewhere, and noted that at vice-regal receptions they regularly ‘fought for and feasted on strawberries and cream.’ Australians did not save money, their chief idea was pleasure and ‘they have no sense of duty, or very little.’ She remarked that ‘the want of religion out in these colonies is very terrible’, and, true to the creed of per class, considered the Labor Party ‘the curse of the country’. She noted the average Australian’s obsession with horse-racing; she herself writes of attending Melbourne Cup meetings and does not mention the name of the winner; she wrote feelingly. ‘… there is one thing I shall be glad of when I get home, I need never go to another race!’

Yet in her public life she was unfailingly kind and courteous, and though a martyr to migraine headaches, willingly and enthusiastically accompanied her husband in the course of his duties all over Australia from Oodnadatta to Brisbane and from Port Lincoln to Hobart, at a time when travelling was arduous and uncomfortable. She wrote feelingly of the plight of the Aborigines; on sweated labor in the cities (she begged the then Premier of S.A., Charles Kingston, to remedy this by legislative action); she was utterly opposed to flogging; and, a conservationist ahead of her time, she would not accept a platypus rug ‘because the poor little creatures have been so killed they will soon become extinct ... I am working now at Premiers and Governors to get them to arrange a universal closed season all over Australia for these native animals, opossums, wallabies, platypus, kangaroos, which otherwise will soon be extinct.’ She worked enthusiastically for the cause of women, willingly acting as patron of their societies, and she founded the Queen’s Home (maternity hospital) in Adelaide, requesting unselfishly that it be so named (after the death of Queen Victoria) rather than the Audrey Tennyson Maternity Home as was originally intended.

She enjoyed meeting and entertaining musicians and artists of all kinds – these include Amy Castles, Elsie Hall, Nellie Steward, Ada Crosley (‘ ... she has brought out a wonderful young pianist, Percy Grainger’) and of course Melba. But, though she recognised Melba’s artistry, she did not like her – ‘as a private individual Hallam and I are not attracted to her.’ She, wrote of Melba’s ‘greed for money, temper and vulgarity’ which ‘made her much disliked in Australia.’

She loved the literature of the new country; she read, and urged her friends to read among others, Rolf Boldrewood and Ethel Turner (‘Seven Little Australians and The House of Misrule … a wonderfully true account of Australian life. Hallam and I delight in them.’) She recorded her impressions of the sights and sounds of Australia with genuine enthusiasm, whether it was the Blue Mountains of N.S.W. (‘I have never seen anything to compare to it at all, the wonderfully brilliant blue of the distant hills, the most gorgeous real sapphire blue, really transparent blue – it is impossible to give any idea of it.’) or of the surroundings of the beautiful summer vice-regal home, Marble Hill, in the Mount Lofty Ranges of S.A. where she and her family spent so many happy times (‘The autumn colouring is so wonderfully rich, not from tints as at home because there are very few tints here, the only ones from the ‘fruit orchards, cherries, pears I and walnuts, but the distant and near hills are the most wonderful blues, quite unlike anything home, and just now the people are burning at off a good deal and the color of the smoke is such a wonderful blue and one watches the great rolling shadows over the hills and gullies.’).

It is not surprising that when Lady Tennyson left Australia, the Lady Mayoress of Melbourne said, ‘There goes the nicest woman we have ever had here’. It seems to me most appropriate that we have these absorbing letters of one of the most gracious of vice-regal ladies edited by another. And one must say that the editing of these letters is superlatively done; the annotations are exactly right, and to cap it all, Lady Hasluck, as well as writing a stylish introduction, adds the splendid touch of a type of epilogue, ‘The Years After’, where she tells what became of Audrey Tennyson in later life until her death. I have not seen this done before in a book this have type and it is a superbly satisfying conclusion.

And finally, full marks to the National Library of Australia for such a splendid piece of book production, a worthy companion piece to the recently published letters of Vance and Nettie Palmer. If it is true, as Thomas Jefferson once said, that letters form the only full and genuine journal of a man’s life, then, in this volume, Audrey, Lady Tennyson, could have no better memorial.

Comments powered by CComment