- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

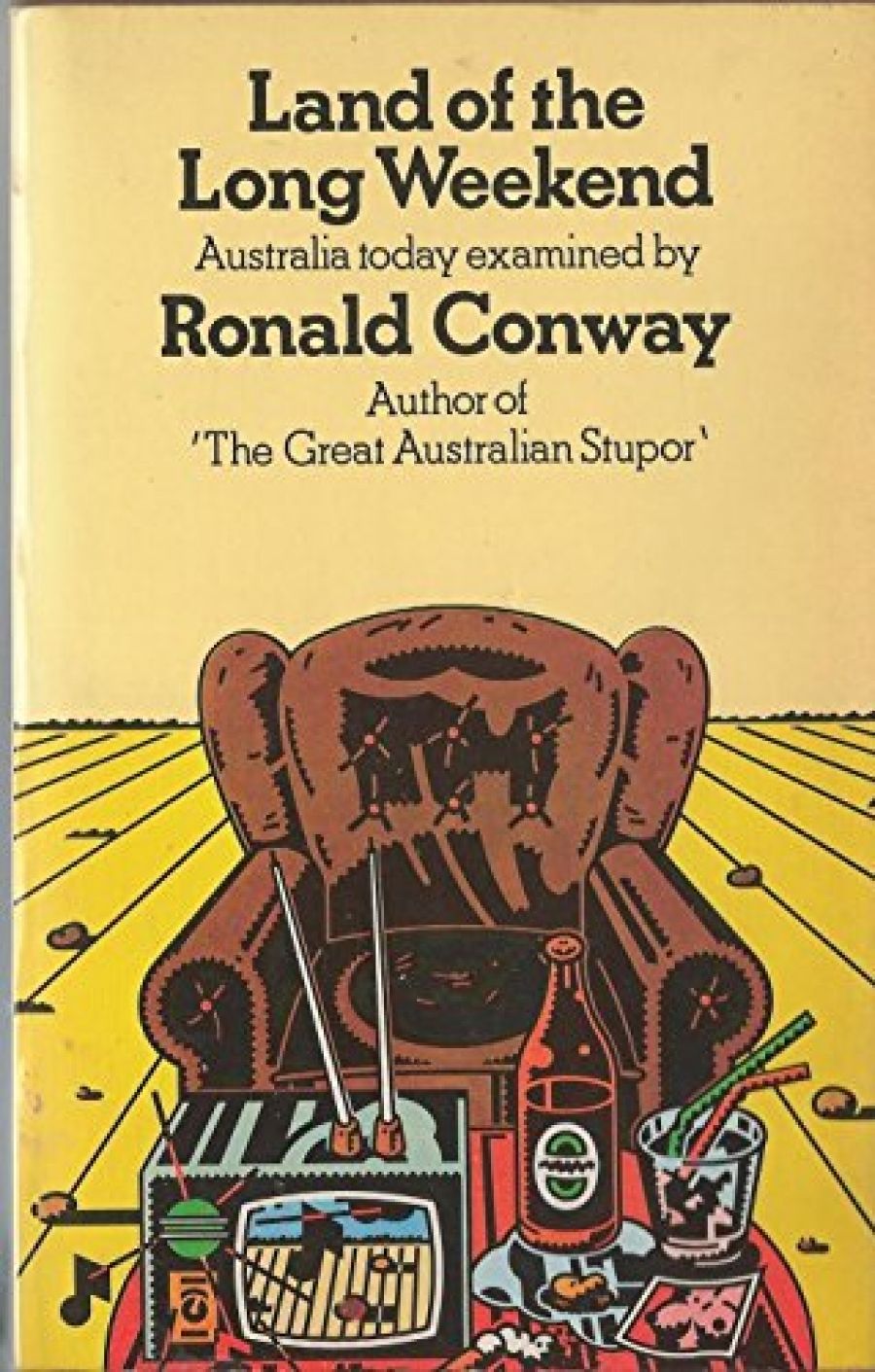

- Article Title: Land Of The Long Weekend

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Melbournians may be enchanted to learn that Conway regards Melbourne as the intellectual centre of Australia, even though he himself shows a nostalgia for the quieter backwaters of Hobart. More skilled at attack than defence, the writer shows the same capacity to come up with broadsides against the materialism and lack of general tenderness which he feels characterises the Australian character, and which also typified his earlier book, The Great Australian Stupor.

- Book 1 Title: Land Of The Long Weekend

- Book 1 Biblio: Sun Books, 372 pp., S4.50, ISBN 0 7251 0280 2 pb.

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Conway sees the family as the central unit of society, and it is a matter of concern to him that this prop to Australian society is being white-anted by materialism, a surfeit of luxuries, and a paucity of moral, ethical and spiritual values. At the heart of much of his analysis is a battle between ‘matrist’ and ‘patrist’ values. Conway defines these terms as follows: ‘values coming from a strong, concerned, but affectionate father who exemplified virtues of self-reliance and civic consciousness might be termed patrist. Those deriving from a contrasting emphasis upon the nurturing personality of the mother – stressing the values of sensate comfort, unconditional communal support and satisfaction and a responsiveness to personal (as against social) commitments – could be called matrist.’

However, largely because the family is not doing its job of providing the aid and the warm, personal relationships required, Conway sees a third strain enter the picture: the peer group, with its values of mateship, sardonic humour and cynicism. This he dubs ‘fraternalist-anarchic’. Conway, with his customary ability to splash the adjectives around, describes the nature of the fraternalist-anarchic style, with its heyday in the period before the 1950s as ‘gutsy, game, loyal, materially generous, bibulously quarrelsome, woman-deserting, incapable of self-analysis or introspection, raucously mendacious and chronically resentful of authority.’ Overall, he doesn’t have much time for this style. He prefers the ‘maturity’ of the patrist-conservative style. He tells us that it is mostly to be found among Australian women, but presumably a few males, such as Mr Conway himself, also have it. The ‘patrist-conservative’ lifestyle is defined as follows: ‘true conservatives usually think for themselves. They can operate as good “party men” only as a wise leaven. They allow for wealth but are contemptuous of greed and the debasement of leisure. The bewildering hypocrisies, the news-speak and double-talk which are so much part of the pseudo-egalitarian trendy social scene are not for them.’

‘Knowing who they are and whence they have come’, he adds, ‘they find it hard to go in for either self-delusion or to be more than politely tolerant of the costly self-deceptions of others. Solicitous for individuals they have no great respect for mobs. They are the “fathers” Australia desperately needs.’

Conway is a man who seems out of step with many of the values (or as he may see it) lack of proper values in contemporary society. In opposition to the levelling forces in society that seek rather to prevent a man or woman from rising above his present level, he is unashamedly elitist, pushing a view of education which favours confining university education to an aristocratic elite, rather than reducing ‘standards’ to satisfy the ‘masses’. It is a familiar problem facing tertiary institutions, whether to promote ‘excellence’ or ‘equality’, i.e., go for high levels of attainment that only a privileged few will meet, or reduce standards so that a better level of overall education will leaven society. Conway goes for ‘excellence’, not only at tertiary level, but also at the schools’ level, where he takes the conservative line that traditionalist education and the ‘Back to Basics’ movement are needed to drill the unintellectual majority into such attainment of literacy and numeracy as they can master.

The contempt for his fellow-Australians is seen in Conway’s description of many workers as turning away from the Protestant work ethic to the ‘shirk’ ethic. An excess of holidays and a dearth of work turn employees into bludgers, a blot on the face of the welfare state. His sympathy is reserved for a few groups, such as some parts of Women’s Liberation, with its more flexible sex-role expectations, and homosexuals, unjustly persecuted in our society. He also feels some sympathy for isolated individuals, while despising Australian society in the mass.

An intellectual gadfly, his book will provide the necessary stimulus to evoke a thoughtful response from the reader. He won’t please everybody, but he doesn’t expect that. As he ends the Land of the Long Weekend, he leaves the thought that ‘if the Ten Commandments or even the Analects of Confucius had waited for consensus, mankind would still be wielding clubs in caves.’

Comments powered by CComment