- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Striking grievances

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One of the great merits of Phillip Deery’s presentation is the way in which he shows the immediacy of the coal strike: its great significance in changing the lives of the miners and in transforming the political situation in New South Wales. It was a time of great bitterness, in which those who expected the interests of the Labor movement and the Labor Party to converge, considered themselves betrayed. Nor did the swiftness of the Chifley government in moving to crush the miners’ strike garner them any favour in the public’s eyes. The public considered the hardships brought about by the coal strike to be merely the latest in a series of events that seem destined to threaten their comfort and standard of living. The communists were blamed for the strike, probably unjustly, for although there were communists among the miners, the vast majority were non-communists with legitimate grievances against the mining companies.

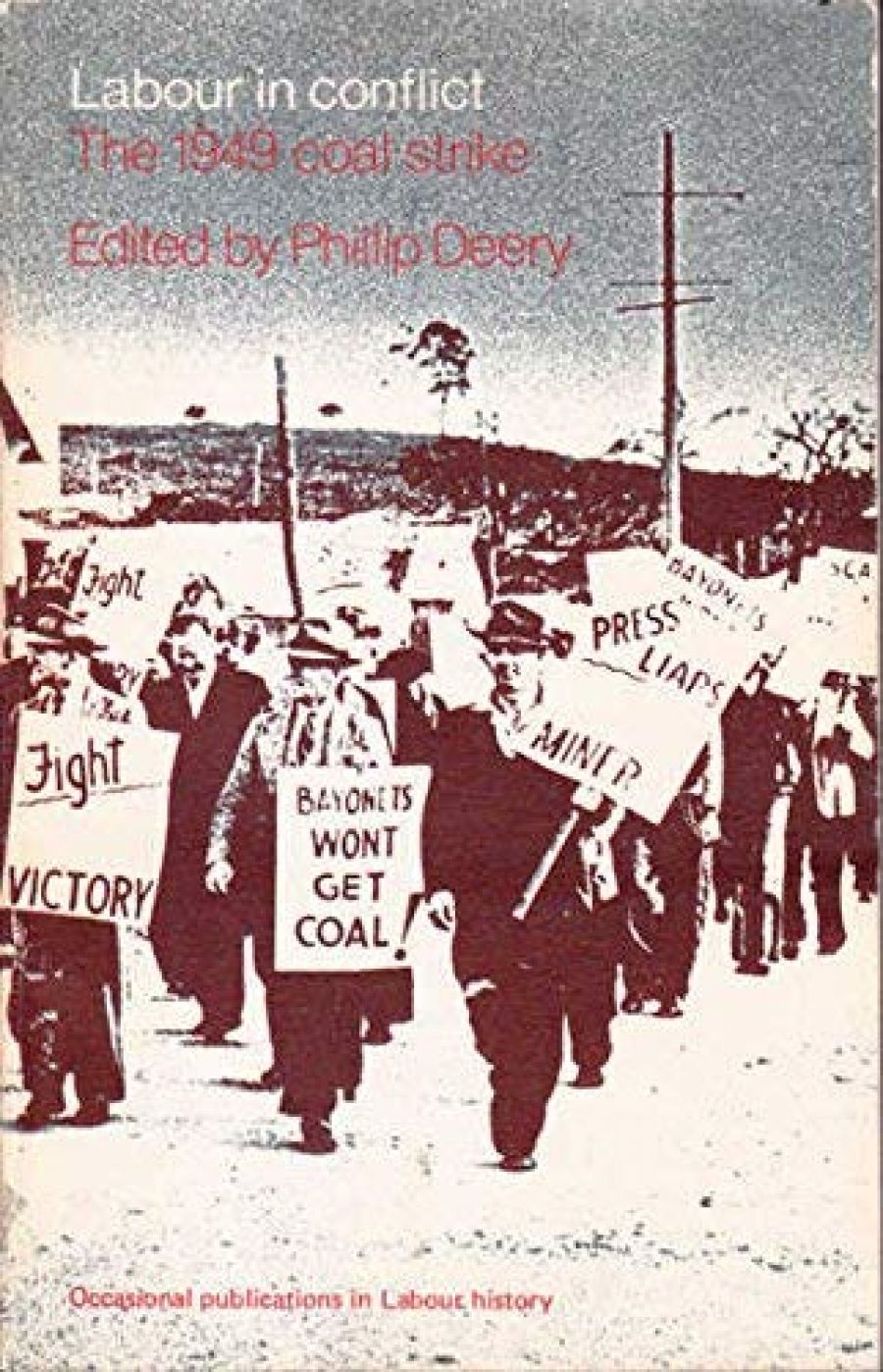

- Book 1 Title: Labour in Conflict

- Book 1 Subtitle: The 1949 coal strike

- Book 1 Biblio: Hale & Iremonger, $11.50, $5.50 pb, 106 pp

Deery’s chapter on ‘The miners’ heritage’ provides a series of primary source documents exposing the hazardous and unhealthy conditions of coal mining prior to 1949. Thirteen men died in the New South Wales pits in the final quarter of 1947, and many more endured a kind of living death from the effects of coal dust on the lungs. One wife of a miner bore witness to its effects:

‘I used to lie awake throughout the night listening to his wheezy labored breathing. When he came home from the pit he’d be coughing his lungs out. There was nothing I could do.’

Poor ventilation, dust, fumes, and high humidity were the rule rather than the exception. And what did they come home to? Shabby, slum-type houses, poorly lit and sewered, health hazards in themselves. As Phillip Decry suggests, this bred resentment, and a feeling that only those who lived under such conditions could understand what they were really like: ‘the miner … saw himself as a pariah in society: vilified and lampooned when on strike, neglected and forgotten when at work’.

The moment they chose to strike was inauspicious because it coincided with anti-communist drive like that of McCarthyism in the United States, and thus it was easy to blame industrial unrest on a ‘communist conspiracy’. Coal had a central part in the economy of New South Wales and when the strike broke industry ground to a halt, unemployment almost reached a million, and the government moved to crush the strike. It cut off funds to the miners, imprisoned union officials, and called in troops to move the coal.

The Chifley Government intended to apply ‘boots and all’ and they succeeded in ending the strike, but the government were to feel the kick of ‘boots and all’ when the electors voted them out of office. As A.A. Drummond predicted: ‘I think the Chifley Government had dug its own grave … when the workers lose their jobs, their resentment is going to be turned against the Chifley government, whose legislation is anti-working class’ (Document 52).

Ben Chifley’s legacy was a legacy of bitterness from those in the working class who felt that their own political brethren had turned against them. The documents, expertly assembled and commented upon by an expert Labor historian, tell their own story better than any massive historical tomes.

Comments powered by CComment