- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The publisher did scant service to the author by putting a ‘blurb’ before the book, emphasising ideas that are neither implicit nor explicit in it. Betty Roland does not claim to be a prophet.

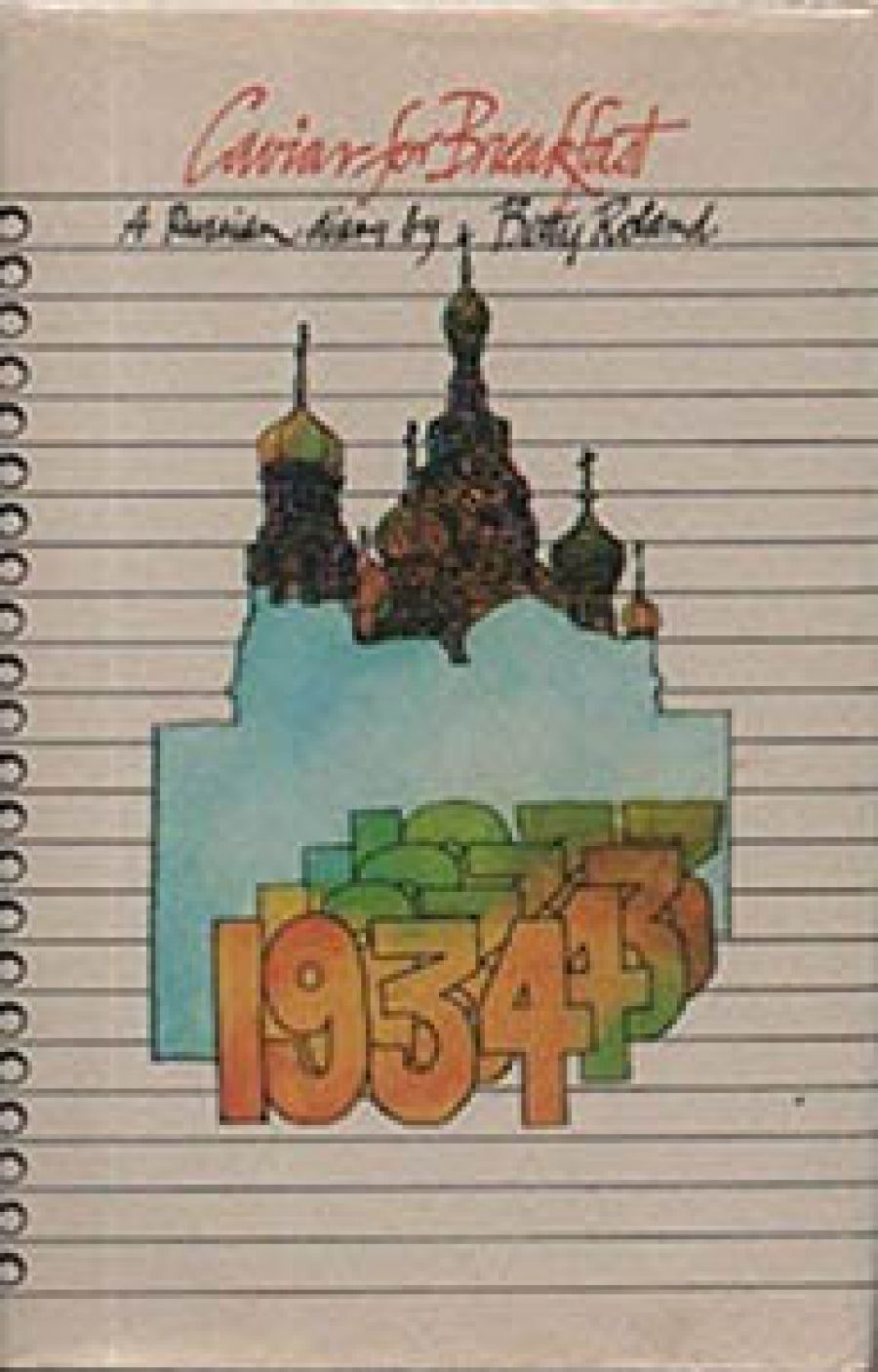

The old cliché ‘I couldn’t put it down’ was literally true when I read her Caviar for Breakfast, the account of her year in the Soviet Union in 1934.

We all do silly things when we are young!

- Book 1 Title: Caviar for Breakfast

- Book 1 Biblio: Quartet, 196 pp, illus, index, $11.95

Melbourne’s ‘bourgeois intellectuals’ must have been shocked and no doubt a little horrified when, in that year, pretty Betty left her much older, ‘middle-class’ husband and eloped with Guido Baracchi, an almost legendary figure in the Left movement, with a string of wives behind him and the reputation of being ‘a first-class Marxist’ which made him synonymous to many with Satan! Their shock turned to horror when it was realised that the couple were bound for Moscow (otherwise Hell) via London where Guido’s third wife, Neura, waited to accompany him to the Soviet Union, a trip long-planned by them both.

The adventures when the trio met are worthy of a Mills & Boon novel. Neura comes out of it best emotionally and, apparently, materially. I remember Betty telling us one evening at the Blue Mountains of the enormous sum of money (for those days) he gave her. We – living on the smell of an oil-rag – were aghast.

Skipping the romantic vicissitudes, I was mainly interested in the contrast of the life in Moscow when I first visited it over a score of years later.

The ordeal of the couple waiting for visas is typical of many stories of that time. Eventually they got to Moscow. Betty was to experience there the trials of a country emerging from semiFeudalism and eighty per cent illiteracy; shattered by four years of World War I, rent by Revolution and Civil War; torn by the intervention of most of the armies of the West for another five or six years; suffering from near-famine owing to the bad season of 1932 and the refusal of the Kulaks (rich peasants) to co-operate with the new agricultural policy – collectivisation.

Betty, true to her class, her upbringing, and her romantic temperament, was horrified. By nature she was apolitical. By education she was the typical outcome of a ‘Ladies’ College’, that is, ignorant historically and socially. Guido, starry-eyed communist that he was (theoretically), was only slightly less horrified than Betty. They were shocked at the number of beggars about. Remember it was after the hunger marches in Britain, the dole marches in Australia, but they had never seen or read about them!! They were disgusted when they found bugs in their bed. Comfortable middle-class, they had obviously never seen a bug.

They were disappointed (to put it mildly) in the food. Outside, people starved! Unfortunately, they never met Isadora Duncan who – romantic that she was in everything else – recorded something to the effect that ‘birth, whether of a person or nation, is inevitably accompanied by blood, pain and sweat’.

Their sufferings in housing, work, and everything else related to living, are told with vividness and that capacity to describe a scene that is Betty’s great talent; she remains throughout incurably bourgeoise, neither understanding nor excusing what she had to suffer. Guido tried to do so, but it beat him. He was thoroughly disillusioned. The only people she really liked were the ex-aristocrats. Their visit to a famous ex-countess is a gem. I remember meeting such a one in Paris, who weighed the egg before buying it! Inflation, or deflation, had ruined the tidy annuity the count left her. I met old ladies in South Kensington existing on similarly reduced allowances.

I wonder if I – an incurable romantic but never a communist – would have reacted as they did if I had gone to the USSR in 1934? I had my first glimpse of Moscow in 1956 and was astonished that not only had they cleared up the things that offended Betty, but they apparently had recovered from the appalling suffering of World War II.

I was twenty-two years older than Betty was in 1934. I have been seven times over twenty years and each time my wonderment grew. Was this the slum-city Betty described in 1934, with its superb Kremlin (she liked that too), its wide streets, its good restaurants, its lovely parks, where children played, summer and winter, and old people (on good pensions) drowsed in the sun?

My husband and I have travelled 82,000 miles throughout the vast country and have never seen a beggar or a bug. We have been well-fed, over-fed, everywhere we went and from the look of the people, so were they.

We found the cultural level very high, collective farmers in far Kazakhstan were preparing an outdoor stage for Moscow ballet dancers.

As for the sanitation that horrified them! Have they never been in China or Jakarta today? I remember my horror when we walked along the quays of the Tiber in Rome in 1955, or the lanes of Menton a little earlier. Open-air lavatories! And the pit-toilet next to the well in Romsey (Mountbatten’s country home). Or was Betty never subject to the ordinary countryside dunny at home? I long ago learnt that the standards of the city don’t apply to the country – and I didn’t like it either.

I wonder if Betty’s reactions were conditioned by the fact that Guido still corresponded lovingly with ex-wife number three? (So Betty says on page 272.) Or that she foresaw that the day would come when he would ditch her too? – which he did. Poor loving, courageous, romantic, ignorant Betty! My heart bled for her, particularly in the awful cold. Moscow – with heating – I can’t bear after November, but the natives say winter is the best time. Great fun! I agree with her, ‘lovely people, these Russians, kindly and warm-hearted’.

If this was intended as a guide-book for the Olympics, it is going to be a terrible disappointment to the Russophobes when they get there.

Caviar for Breakfast is a trivial title for a tragic book.

Comments powered by CComment