- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The mastery of words

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his introduction to The New Australian Poetry, reviewed elsewhere in this issue by Thomas Shapcott, John Tranter declares that this poetry has no allegiance except to itself. Some characteristics of works regarded as modernist are: ‘self-signature’ – the work validates its own technical innovations – and self-reference, where the ‘method’ is reflected consciously in the ‘medium’. He contrasts this modernism with such work as Vincent Buckley’s ‘Golden Builders’, which elicits a response of ‘quasi-religious rhetoric . . . a natural outgrowth of Australian university English departments’, and one sufficient to explain the ‘anti-academic bias’ evident in much of the work of the new poets.

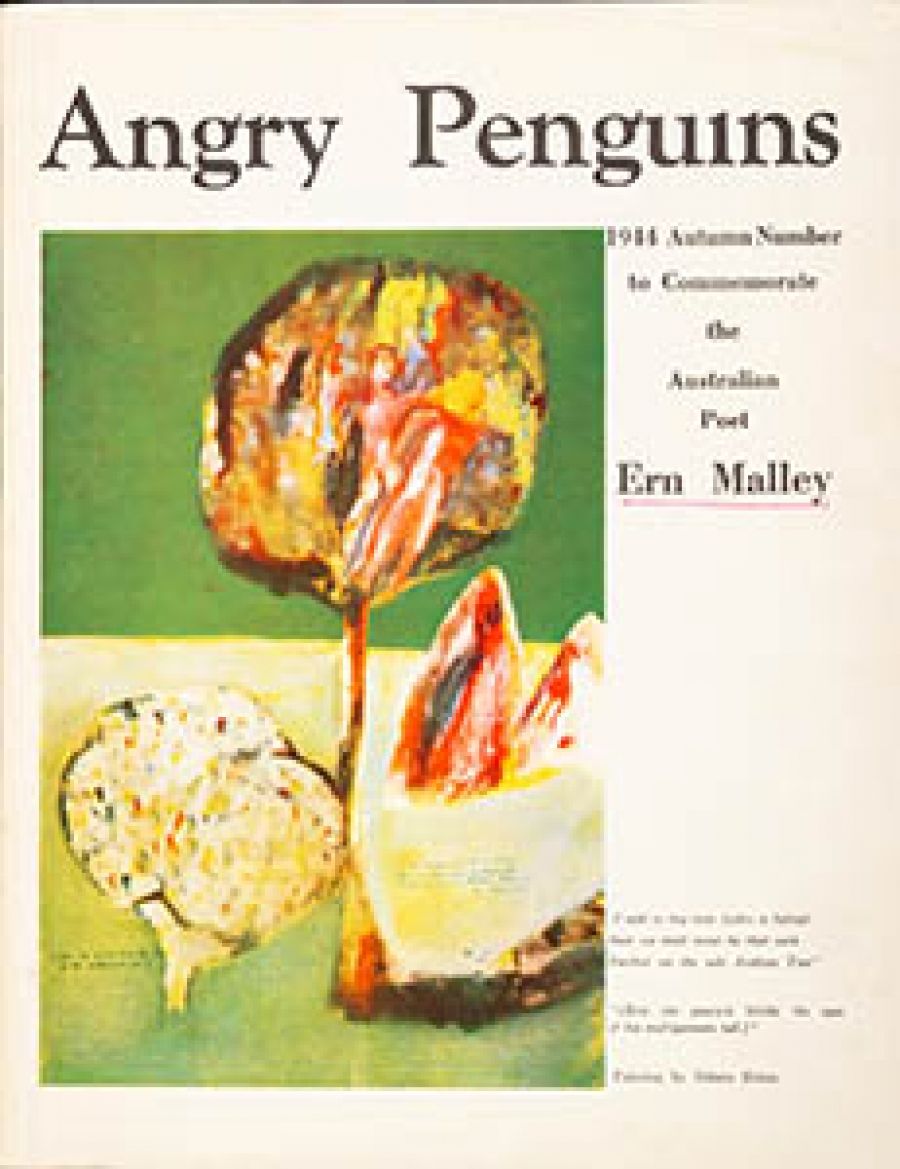

- Book 1 Title: Angry Penguins

- Book 1 Subtitle: 1944 Autumn Number to Commemorate the Australian Poet Ern Malley

- Book 1 Biblio: Limited facsimile edition, $5.95

- Book 2 Title: Poetic Gems

- Book 2 Biblio: Mary Martin Books, 50pp, $4.95

A similar attitude appears in the Preface to Max Harris’ latest collection, where he writes:

The jongleur thinks of poetry as a special language. But there’s nothing special about the words. The colloquialism, the lofty word, the cliche, the abstract word – they can all be made to serve the same master; poetic language.

Besides, if we remove the linguistic mystique from poetry then the literary academics will have to become honest dole-bludgers, which is a desirable state of affairs.

In the pursuit of this autonomy, this imperviousness to reason, Harris adds that, in his poetry, he has ‘tried to eliminate the personal signature’. In this aim he has failed. His verses, with their abrupt changes of tone, their vulgarisms, their appeal to popular prejudices, and their literary name-dropping, are as personal, as idiosyncratic, and as profound as his Saturday newspaper columns.

Such an outcome is an inevitable result of the poetic theory enunciated in his preface. If, as he says, poetry should be about the world, then there can be no poetic language – only words used to make poetry. But these words must be given a meaning, they must enable us to see the world afresh, and they must therefore offer us statements which can be discussed. Fortunately, Tranter’s poets, despite his theories, and a complexity of language which often requires careful unravelling, do this. Harris, for all the ostensible simplicity of his words, does not.

Or at least not often. The first poem in the book, ‘Bud in Perspex’, is one of the few which shows a true poet trying to escape from the postures.

The rose in perspex by my bed.

Watches each move of my head.

It will bloom when I am dead.

The romanticism and the concern about death are the key to this collection, which elsewhere mainly avoids facing these facts. Yet the same romanticism is also the clue to Harris’s part in the Ern Malley affair, now usefully recalled by the publication of a facsimile edition of the 1944 issue of Angry Penguins in which the hoax was perpetrated. Reading the issue at this distance in time, it seems that the offence was not so much the poems themselves as Harris’ awestruck introduction to them.

As has been said before, the poems, whatever the intention of their authors, contain genuine poetry better, in fact, than some of the orthonymous work of the poets who concocted it. Had the supposed author, ‘Ern Malley’, not been said to be dead, it is probable that the editors would not have published the whole collection as it stood, but in the circumstances they understood to be true, they were certainly right in making them available to their readers.

It should also be pointed out that this issue of Angry Penguins contains a wealth of poetry, art criticism, fiction, and cultural commentary, much by writers who have gone on to eminence in these or other fields, which justify its re-issue quite apart from its relevance to the cause celebre.

Yet this context makes it clearer that too many of the Ern Malley poems are merely gestures towards meaning offering themselves for the reader to complete. In this way, they reinforce the reader’s self-esteem rather than correcting his view of the world. There is a suspicion that the denser poems in the Tranter collection may do no more, and that they in fact operate at no deeper level than such a Harris verse as:

I’m shagging in the wagon

Just shagging in the wagon

What a glorious feeling

To be shagging in the wagon

Such trivialising of language is also a trivialising of feeling, and indicates that the poet, rather than commanding his words, has joined his age in being commanded by them. It is the same language of commercialism and propaganda which enables world leaders to justify naked aggression in terms of helping their allies, or to condemn the aggression in terms of international standards they have never observed themselves. When language can no longer tell the truth we become its victims. The poetry which will command our attention will be the poetry that restores this truth to us.

To deny, as both Tranter and Harris appear to do, that poetry can serve this function, and that the poet has a moral function in society, is not to assert artistic independence but to rob art of its value, and thus to surrender humanity to barbarism.

Comments powered by CComment