- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A chronicle of colonial powerlessness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The dilemma faced by the Australian film industry after a decade – and about fifty feature films – of revival is neatly put by the Foreword and the Introduction to The New Australian Cinema. One kind of pioneer, Phillip Adams, to whom some credit for the early impetus is due, has one kind of warning. ‘Our politicians, film corporations and investors are insisting on the need for commercial success in the U.S.’, he says, and reminds us of the reasons some of us thought an Australian film industry was important: ‘We needed to hear our own accent. We wanted our voice to be heard in the world.’ Another and earlier kind of pioneer, Ken G. Hall, speaking from the bitter experience of the immediate post-war years (when, as he says, ‘I made newsreels’) has the opposite warning; ‘There will be no enduring film industry in this country unless it is based on commercially successful films.’

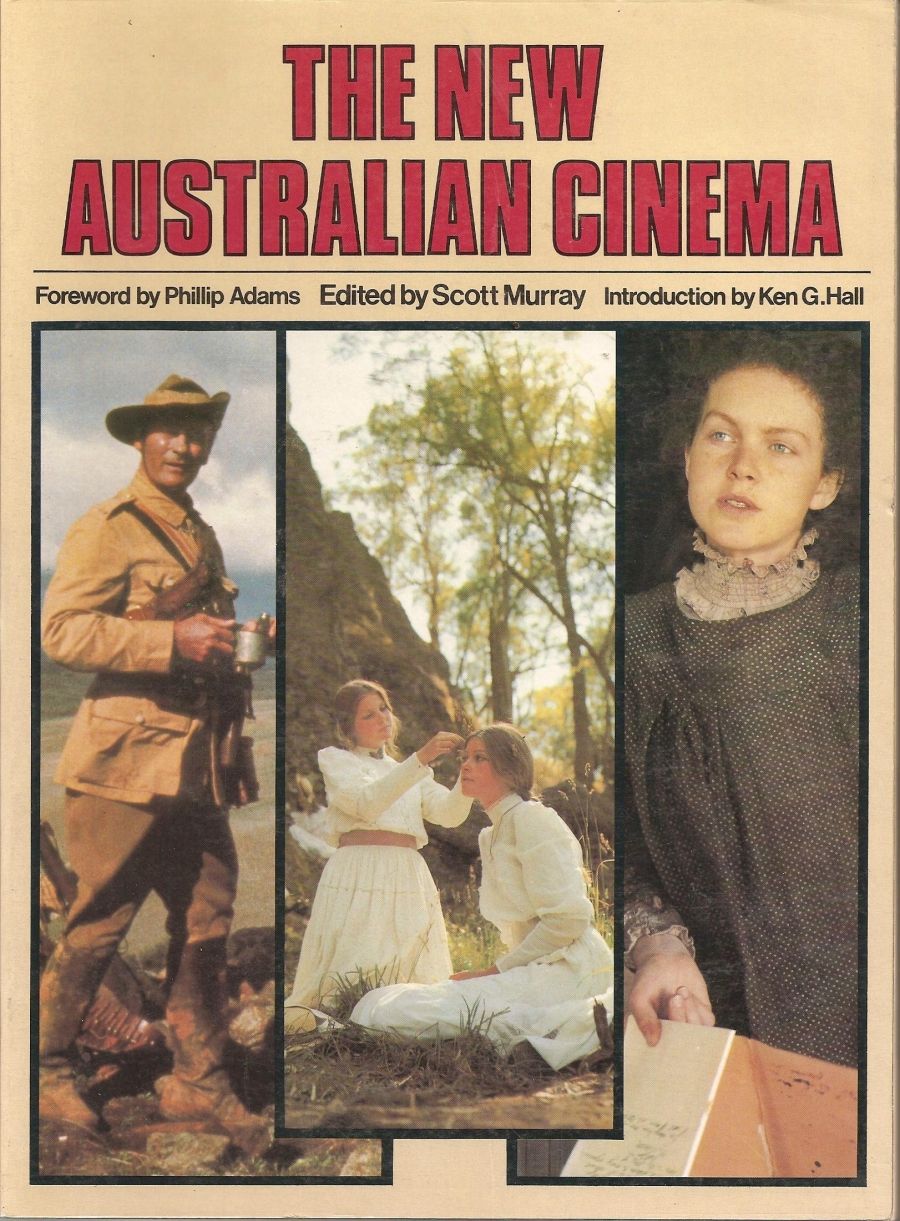

- Book 1 Title: The New Australian Cinema

- Book 1 Biblio: Nelson, 207 pp, $14.95 pb

The current arguments about the future of Australian films all hinge around the issue Hall and Adams polarise – such questions as the number of foreign actors to be allowed by Equity, the dubbing of voices for foreign markets, whether films should be designed for the local or the international market, whether the Australian Film Commission should take commercial or artistic promise as its criterion for funding. The polarisation reflects in part the position of the book’s source. Cinema Papers is a magazine which has, in the course of becoming an established and very valuable publication, sometimes appeared to be uncertain of its role. It is both a trade paper, concerned with nuts-and-bolts issues and filled with interviews with filmmakers, actors, cinematographers, even distributors, and at the same time a critical journal attempting objective evaluation of the trade’s efforts and making intermittent attempts to keep in touch with the larger film world of overseas production, critical developments, and scholarship.

That it has managed to bring off, more or less successfully, such a balancing act is a tribute to the skills of its editors, Scott Murray and Peter Beilby, over the seven years of its existence.

The contents of the book, after these introductory allies, come down firmly on the Adams, or local culture, side of the argument. In a series of chapter categories uneasily divided between genre and broad thematic groupings, a number of writers survey the decade. While the thematic groupings (loneliness and alienation, human relationships, and sexuality) are more obviously concerned with the ways in which a decade of films represent Australian life, the other categories (comedy, social realism, action and adventure, fantasy) clearly share the same interests: all of them though (and this is a problem with the book) waver between considerations of this sort and a kind of critical history. There is a continual shifting between the what that is said, sown or reflected, and the how of its doing, and so understandably and almost inevitably, two questions become confused. The issue of how well and in what depth Australian films represent Australian life, attitudes, themes, and values gets mixed up with the more popular question, ‘how good are Australian films?’, a question given more urgency by the cultural cringe mentality.

The form of the book presents a further problem, equally inescapable, and that is the inevitable overlap between chapters or categories; a film like Newsfront, for example, can be given detailed consideration in four chapters and referred to in several others. Although in general there is consensus in the judgements made, there are exceptions, and these at least serve the purpose of isolating those films where critical disagreement has been strongest. In Search of Anna, one of the more interesting failures of the last few years, provokes opposite opinions from Brian McFarlane (‘ … fouled-up narrative habits … flashy technique … pretentious in its thematic interests …’) and Susan Dermody (‘ … a complex exercise in ordering the narrative out of time and space, sequence and logic, so that the theme of mental disorganization and conflict is enacted on the level of narrative structure’). My sympathy in this difference goes towards Dermody, not only because of the very real merits of the film, but because the narrative structure on which the two writers differ represents one of the few attempts in the decade’s Australian films to rise above a dreary linearity and an equally deadly literalness of style.

The different contributions vary in quality depending on the talents of the individual writers and the manageability of the individual categories. Some, especially Meaghan Morris’ on ‘Personal Relationships and Sexuality’, and ‘Loneliness and Alienation’ by Rod Bishop and Fiona Mackie, engage urgently with some of the larger questions about Australian society, and in both a perceptiveness about these questions is matched by a real understanding of how films work. Morris points out that ‘… one of the most interesting and ambiguous aspects of Australian feature films is that they have rarely, if ever, treated sexual relationships in isolation, or exclusively for their own sake’ and, later, that, ‘At the centre of the representation of sexual relationships in Australian cinema is the mark of an impossibility of some kind: in the study of the ways of one tribe, personal difference and individual emotion have very little place.’ What is interesting about the Bishop-Mackie article is the way it centres unerringly on the films that are important, and subjects them to economical and illuminating analysis. In particular, connections are drawn between two films from the beginning and end of the decade. Burstall’s 2000 Weeks (1969) and Noyce’s Newsfront (1978), a comparison which goes some way (but not far enough) towards justifying some alarming generalisations about Australian life in the opening paragraphs.

Both of these chapters are important in that they attempt some sort of overview of what Australian films have shown us; they help us understand how the films have contributed to our understanding. Adrian Martin’s chapter on ‘Fantasy’ is sharp and perceptive in its analyses of a number of key films without ever exploring the intriguing questions concerning their particularly local contexts. Patrick could be set anywhere but Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Long Weekend seem, in their different ways, utterly indigenous; it is a pity this otherwise excellent chapter did not examine why.

In two chapters, the writers win our sympathy at once. ‘Horror and suspense have not been major elements in the Australian film renaissance of the 1970s’ says Brian McFarlane in his chapter on ‘Horror and Suspense’, and it is easy to agree with him. It is less easy to agree with some of his critical judgements, as he consigns not only the aforementioned In Search of Anna, but an equally imaginative work, the Patrick White/Jim Sherman The Night the Prowler to the critical scrapheap. Geoff Mayer may have been justified in a similar comment in his chapter on comedy, for there has been precious little of it throughout the decade. He has chosen the strategy of looking at humour in Australian films – and thus Sunday Too Far Away, hardly ‘comedy’ in a traditional sense, merits two pages with extensive quotes – rather than developing his preliminary examination of Australian humour into an exploration of the difficulties of creating comic forms in Australia. It is surprising, too, that The True Story of Eskimo Nell is treated briefly and dismissively, and Eliza Fraser and The Great McCarthy are not mentioned.

There is a thoughtful, and useful, chapter on children’s films from Virginia Duigan, a thought-provoking and splendidly succinct chapter on the history of Australian film by Andrew Pike, and a workmanlike chapter on ‘Social Realism’ by that most perceptive and readable critic reviewer, Keith Connolly. Sam Rohdie’s chapter on the avant-garde is a valuable and lucid contribution. Overvalued in some film cultures, the film avant-garde has been undervalued in Australia, and some of the outraged or bewildered reviewers’ reactions to this chapter point to the apathy and intellectual sloth that may be at the root of such a response.

The one chapter that worried me was Ton Ryan’s on ‘Historical Films’, for two reasons. In two and a half pages of ground clearing, the author attempts to establish a critical position which rejects genre and auteur theory, has a lot to say about the way (via Metz) narrative realism tends to conceal its status as a language, and culminates in the unremarkable statement that history is not objective or impartial and that therefore (presumably) what we see in a historical film is not to be confused with ‘some simplistic notion of historical accuracy’. Both the stated and the implied proposition we could well have concurred with, without the didacticism of the process by which they are arrived at.

The second worrying thing about the chapter is that it sets out on a justification of, to put it mildly, one of the more problematic Australian films, Eliza Fraser. Seeing it as a parody, Ryan berates critics for being literal-minded, for failing to go beneath the ‘surface rumbustiousness and the apparent disconnectedness of its picaresque narrative’. It was all the critics’ fault (and, one assumes, the audiences’ too) because

a determination to see the film as simply belonging to the tradition of Stork … and Alvin Purple … seems to have encouraged a superficial response to the place which the film’s treatment of sexuality occupies within its broader thrust.

A film which needs that kind of sentence is in trouble already. In fact, Ryan’s often ingenious and persuasively argued case fails to convince this reader that his initial response to the film was in any way off-target. Eliza Fraser was an unholy, unlovely, and unfunny mess. It was not preconceptions or the literalmindedness of the critics or audiences, but the ineptness of the film, that destroyed it. Despite this, Ryan’s article has some fine and perceptive points to make, particularly those emerging from a comparison with the treatment of history in American films – the powerlessness of the Australian character, the recurrence of the defeated battler image, the individual as ‘consumer of history rather than participant in its course’. (Much of this is so well done that one wonders why the long critical wind-up was necessary.) It is in this sort of revelation that the book justifies Australian cinema, and Australian cinema justifies itself.

Comments powered by CComment