- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Leader with harm and aggression

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Success may not always have come easy to Robert James Lee Hawke, but it has come often. In 1969 he became President of the ACTU without ever having been a shop steward or a union organiser or secretary; he had never taken part in or led a strike. His experience at grass roots or branch level in the ALP had not been extensive when he was elected Federal President of the party in 1973. Now, untested in parliament and government, his jaw is firmly pointed towards achieving what has always been his ultimate ambition – the prime ministership.

- Book 1 Title: Bob Hawke

- Book 1 Subtitle: A portrait

- Book 1 Biblio: Methuen, index, illus., 224p., $12.95

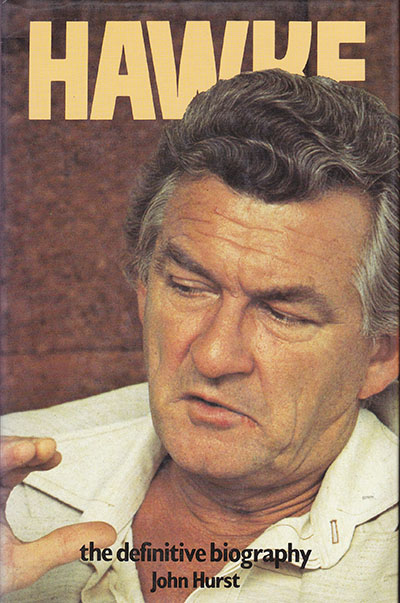

- Book 2 Title: Hawke

- Book 2 Subtitle: The definitive biography

- Book 2 Biblio: Angus & Robertson, illus., index, $12.95

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/Archive/Hawke Hurst.jpg

Both of these books span the fifty years of Hawke’s life from his birth on 9 December 1929 to that long-awaited, highly publicised, and somewhat anticlimactic press conference on 23 September 1979 when he announced that he would seek pre-selection for the Federal seat of Wills.

Both authors make the point that Hawke announced his candidature at a time when he had recently suffered some of the worst defeats of his career. At the ALP Conference in July 1979, to his intense chagrin, he had been outmanoeuvred by Bill Hayden on Labor’s policy to control prices and incomes. Not one to take defeat easily, he was later heard by journalists to refer to his leader as ‘a lying cunt with a limited future’, to certain delegates as being ‘bloody gutless’, and to the fact that as far as Bill Hayden and he were concerned, ‘it’s finished’.

In Melbourne a couple of months later, Hawke lost again at the ACU Congress. First the key candidates he supported for the executive were not elected. Then, despite Hawke’s vehement opposition, the Congress overwhelmingly reversed its former policy of limited support for uranium mining and processing. So keenly did Hawke feel this defeat that several of his colleagues felt he would be reluctant to run for parliament, knowing that he would be getting off the mark as a loser.

Yet only four days later Hawke (‘his voice trembling’, according to one observer) told sixty reporters at a special press conference that he would seek preselection for Wills. ‘I have done what I believe is best in all the circumstances.’ He would, he said, ‘match the thoughts and aspirations of the great majority of Australian men and women’. He would ‘weld Australians together’.

Here is Hawke the healer; the voice is that of reason and moderation; the policy is consensus. Are the words of the same man who, as ACTU advocate in the 1965 national wage case, referred to the ‘stupidity of former decisions of the Arbitration Commission’? Is the picture he paints of himself consistent with the one the nation saw on television in 1971 when, with ruthless ferocity, Hawke, then president of the ACTU and a director of Bourke’s, the ACTU store, destroyed the case for retail price maintenance presented by a spokesman for the Dunlop group of companies, and justified a union ban on the Dunlop group until they capitulated? Is this the Bob Hawke listeners to a PM program on ABC radio in July 1979 will remember shouting, ‘Don’t lie’, across the line to Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser?

How many faces does Bob Hawke have? The question is an odd one to ask about this man who has been a well-known public figures for two decades and who, in the past eleven years, has consistently received wider media coverage than any other political figure in Australia – than any other Australian, in fact. Hawke has been a honey-pot to the media bees, and not only because of the importance of the positions he has held. His predecessor as president of the ACTU, Albert Monk, never attracted the same attention as Hawke; nor did Neil Batt, his successor as ALP president.

It has been said of Fraser that the personality he chooses to project is leaden or wooden. In this way he can bore people, turn them off politics, in the belief they will then be content to retain the status quo, with himself as leader. In contrast, everything Hawke does turns people on; he forces people to respond. Because of his readily observable qualities of aggression, articulateness, dedication, determination, and charm, yes charm, he is seen by some as a Ron Barassi of Australian politics. John Hepworth recently used a similar metaphor, although he reversed it in Hawke’s favour: ‘Phar Lap had whatever it is that makes charisma ... he was sort of the Bob Hawke of horses in his time.

Public opinion polls throughout the 1970s consistently showed Hawke to be the most approved political figure in the country. Various studies indicated that people admired his frankness. His public displays of emotion probably endeared him to more people than they alienated. Even his confessions about his drinking habits seemed to work to his advantage. ‘Let’s face it, Hawke is a pisspot like us,’ one investigator was told, ‘(Fraser) wouldn’t know how to have a drink. Not like Bob Hawke.’ The Sydney Sun commented on a television interview by Hawke in 1975: ‘What an amazing interview with Mr. Bob Hawke last night. Mr Hawke’s account of his drinking ways must rank as the most self-revealing interview by a political figure in Australian history. The same kind of frankness – not just about drinking – would be welcome from many other political figures.’

Yet, despite Hawke’s willingness to talk about himself, and the equal readiness of most people who have known him to have their say too, and despite years of intense media coverage, Hawke remains a mystery to many. The Financial Review commented in 1976 that ‘Hawke’s personal philosophy is not widely known’. In 1979 The Australian wrote: ‘We simply don’t know what he is. We’ve no idea what he stands for really, and that is interesting in itself ... Would he be for smaller Government? Where would he be on taxes? We don’t really know. He’s very much an unknown quantity.’

In his Foreword to Hawke, John Hurst writes: ‘There have been times when I have said to myself and have felt like saying to him: ‘For God’s sake take off the grease paint and forget the roar of the crowd. Will the real Bob Hawke please stand up!’ Since the mid-1960s, when he was industrial affairs writer for The Australian, Hurst has been a close observer of Hawke’s career. It is clear throughout his book that Hurst has become very close to Hawke. He gives enough hints to show that he knows more about his subject than he has written, particularly those few areas of his private life which Hawke himself has not made public. But Hurst is not interested in gossip and, apart from a brief excursion into Hawke’s school days, he managed to avoid trivia. He knows Hawke well; yet even he has not penetrated the grease paint. That might be a little disturbing for those millions of Australians who one day expect to see Hawke as their prime minister. Is it possible they don’t really know what is behind the craggy face that has been thrusting itself at them for so many years? One doesn’t expect ever to penetrate the Fraser image, or even the Hayden one, but Hawke surely is different.

Hurst’s book makes us wonder whether Hawke is so different. So does Pullan’s. Robert Pullan says he has ‘tried to give an account of the sort of person Hawke is’. He has known Hawke neither as long nor as intimately as has Pullan, and was far removed from Hawke’s stage for half of the seventies. The main sources for his book are his own interviews. Probably he interviewed fewer people than Hurst, but he quotes them at greater length. Sometimes Pullan makes it clear that he endorses the opinions he is quoting; at other times the reader is not so sure. Certainly Pullan is much more judgemental of Hawke than is Hurst. Clearly both men admire him, but both admit to not fully understanding him.

Pullan alludes to faults which might only be implied, if mentioned at all, by Hurst. On several occasions he refers to Hawke’s enormous ego and driving personal ambition, but concedes that these are not necessarily faults in a leader. What worries him more is his view of Hawke as ‘a campaigner whose radicalism (is) a posture’. He devotes his final chapter to Hawke’s press conference on 23 September 1979. Clearly Pullan is disappointed with Hawke’s performance, especially with what he sees as the shallowness of Hawke’s claim that he was ‘concerned about the condition of the country’. Pullan was disappointed with what Hawke did not say on that occasion, or indeed on other occasions. ‘He did not tear into those who were creating and perpetuating injustice and cruelty. He did not voice a passion for a new Australia in which the poor, the weak and the dispossessed would inherit the land while the rich would be sent away empty. He did not say how his hand would mould his country’s future ... anybody could vote for him’.

Pullan wants a visionary and a reformer and is disappointed that he does not find one in Hawke. The limited nature of his research also prevents him from finding other qualities in Hawke. But then Pullan admits to these limitations when he says his book is not a biography, is not a political and industrial history, but is a portrait. It’s a portrait painted by many hands, though; and, while the dozens of personal anecdotes, memories, and reflections provide an interesting picture of Hawke, one cannot but feel that it’s a fairly superficial one.

Hurst’s book, on the other hand, is a work of scholarship. He has been much more selective than Pullan in his use of comments by the many people he interviewed, including Hawke himself. But the real strength of the book lies in the success of Hurst’s stated objective ‘to delineate a multifaceted character by setting him centrally in the political and industrial events in which he has been involved’. To do this Hurst’s research took him to transcripts of national wage cases, records of ACTU congresses and executive meetings, minutes of ALP meetings, and union records. The result is a most impressive account of the major industrial and political events of the last two decades. At the centre of many of these has been Bob Hawke, a towering figure indeed.

Hurst shows the reader aspects of Hawke that are outside the scope of Pullan’s book: his incredible capacity for work, his incisiveness as an advocate, his ability to reconcile hostile factions, his astute political sense, and even what Hurst called his ‘penchant for Messianic missions’. In case you are wondering how Hurst manages to do all this in a book only thirty-eight pages longer than Pullan’s, the answer lies in the size of the print and the number of pictures. In fact Hurst’s book contains almost twice as many words as Pullan’s. Hurst, by the way, denies that this is an official, authorised biography; the silliness of the subtitle of his book – ‘the definitive biography’ – must then be attributed to the publisher.

Both books are welcome, for they attempt to do different things with their subject. Both are written by journalists who are aware of the cynicism attributed to many in their profession, but who display none of it themselves. They care about their subject and, more important, they care about this country which Hawke may yet come to lead. That is why they both wish they had come to know the man better. I’m sure they will, as will the rest of us; but I would not like to predict what the future has yet to reveal about this remarkable man.

Comments powered by CComment