- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Petrovs – a new dimension

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When I was in London working on a book that Nicholas Whitlam and I wrote on the Petrov Affair, I became friendly with Dr Michael Bialagouski. Bialagouski and I went out several times with our wives to places selected by Michael; a gambling club that had once been run by George Raft, a Chinese restaurant that had a reputation in intelligence circles, that sort of thing.

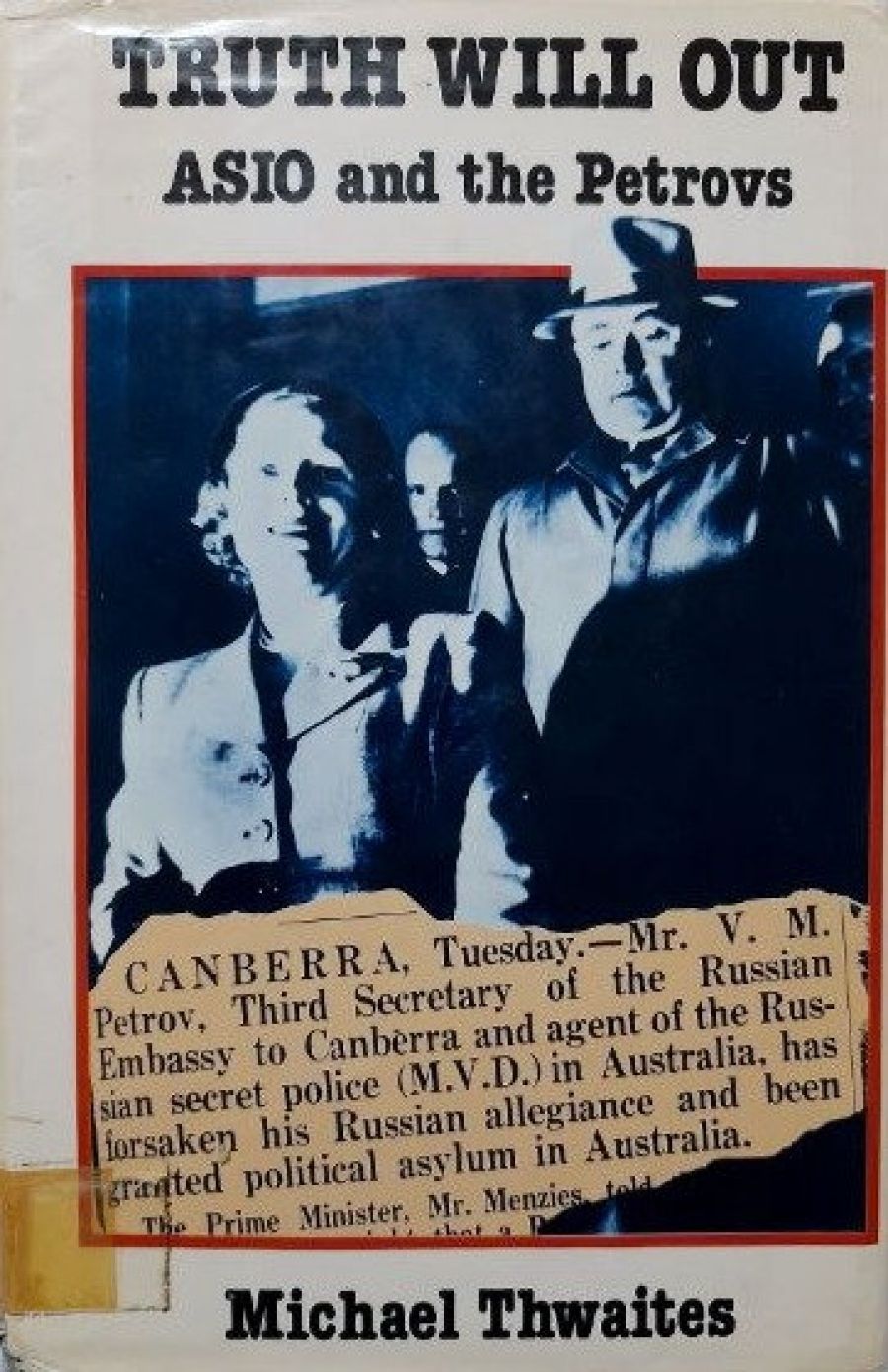

- Book 1 Title: Truth Will Out

- Book 1 Subtitle: ASIO and the Petrovs

- Book 1 Biblio: Collins, 214 pp, $14.95

Bialagouski had once been first violin in the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, his wife, still an extremely handsome woman, had been a well-known actress. He drives his Jaguar fast and well, he’s a perceptive, engaging character. One can understand his appeal to Petrov, whom he drew into the seductive ways of ‘freedom’, Kings Cross-style.

One night, when we were having a nightcap at our flat my wife asked Bialagouski two questions. which, I think are still relevant to a judgement of the Petrov matters, and of the Thwaites book – from its pompous title to its pejorative Cold War 2 postscript.

The questions were, simply, ‘Was Petrov really as dreadful as you have described him?’ and, ‘If he was, if there was nothing likeable about him, how could you pretend to be his best friend for so long? It just doesn’t seem like you.’

Bialagouski had described Petrov as a drunken incompetent bully who bought and abused women, who lay in a stupor while Bialagouski rifled and copied the contents of his pockets, a man who was more concerned when he defected about what would happen to his Alsatian dog, Jack, than about the fate of his wife.

The answers were simple. ‘Petrov was a pig, Bialogouski said, and then went on to tell some more horror stories about Petrov’s behaviour.

And how could he centre his whole life for so long about a man like that?

The answer took the whole room back to the atmosphere and intensity of that period.

Many people are now concerned about the ‘War. Be in it’ crusade that is engaging some sections of our media and society. It pales beside the extremes, passion and injustice of our McCarthy period.

‘It was war, and no sacrifice was too great, Bialagouski said.

Now we have this very reasonable man, Michael Thwaites, to tell us what really happened. A very different picture of the Petrovs is presented.

An extreme view of him is that he was an alcoholic, incompetent, Beria supporter who had stuffed up his job and saw the prospects of making a quid and didn’t mind who suffered. In Thwaites’s account he emerges as a precursor of Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov. At the core of Thwaites’s book, and its title, is his denial of claims that it was all a put-up job to save the Menzies Government.

He has phrased the central question to suit his own purpose, in the most simplistic terms, along these lines: ‘Was the Petrov Affair simply a bit of Australian domestic political drama brilliantly stage-managed by Menzies?’ or, ‘Was it a triumph for the unquenchable human spirit, the unyielding realisation of justice, freedom, free enterprise and ASIO?’

The answer, I believe, is that it was a bit of both, with a fair amount of emphasis on the domestic. Thwaites maintains it was exclusively the latter.

The central question in the argument between these two schools of thought is ‘When did Menzies know?’

On this depended the timing of the defection; the Royal Commission and the election. Apart from a bland assertion based on Spry’s already published claims, Thwaites adds nothing new to this debate.

For the Menzies-ASIO-Petrov-anti-Labor conspiracy theorists the relevant dates are:

* January 28, 1953 – News Week 01, published by Santamaria ‘s Catholic Social Studies Movement, says ‘startling repercussions are expected to follow disclosures soon to be made on activities of certain members of the Russian diplomatic staff in Australia ... take the case of the Third Secretary (Petrov) .. .’* September 2, 1973 – Bialagouski says he told Menzies’ secretary Yeend (now, as Sir Geoffrey head of the Prime Minister’s Department) at the Prime Minister’s office in Parliament House, Canberra, about Petrov.

* February 10, 1954 – Menzies ‘first hears Petrov’s name from Spry’ – according to Thwaites. Evan Whitton, now editor of the National Times, was told this date by Spry in I 973. Thwaites at no stage claims he was ever witness to any discussions between Spry and Menzies on the Petrovs before the defection.

* April 3, 1954 – On the second last day or the Parliament, in Evatt’s absence. Menzies announces Petrov’s defection and the decision to establish a Royal Commission.

* May 29 – 1954 Menzies wins election.

* August 12, 1954 – Menzies in Parliament: ‘I say to the House and to the country that the name of Petrov became known to me for the first time on Sunday night, April 11.’

In the end it comes back. I believe to one’s personal judgement of the credibility of those involved.

I had a number of meetings early in 1974 with Dr John Burton, a man different in character to Bialagouski, but no less affected by the extremes of the last Cold War. One meeting was over lunch in a students’ canteen where we were joined by Nicholas Whitlam shortly after Gough had appointed Sir John Kerr as governor-general. Burton was coldly furious, and recounted Kerr’s involvement in and fascination with the shadowy power play of the security services (particularly his involvement with Dr Alf Conlon in the Directorate of Research and Civil Affairs during World War II). Reading Thwaites’ disclaimers of domestic political consideration or manipulation I recalled a story he told then in 1974, that now seems to have more bite than it did six years ago.

In 1954, Burton, then living on a farm outside Canberra, rang Evatt and said he wanted to give him some information which related to some of the claims ASIO had been making at the Royal Commission. The call went through a one-person exchange Burton knew was often monitored. Evatt, fairly typically, arranged for Burton to meet him at his office in Martin Place, Sydney, at 6.30 am on the following Sunday morning. When Burton arrived, he happened to notice Kerr, sitting on a bench with his snowy hair and rubicund features partly obscured by a Herald Sun and a tree. He was one of the few people in Sydney who could positively identify Burton by sight. Kerr, not famous for reading his Sunday papers at dawn in Martin Place, scuttled off. His place was later taken by a man Evatt believed worked for ASIO.

Perhaps Burton told the wrong Whitlam story, a little too late.

Someone, rather back-handedly, once said to me that it was impossible to write a dull book about the Petrov affair.

Thwaites writes well. He’s idealistic, in a nice way – he wants the goodies to win – but, to me, he is either a little naïve or disingenuous. For amateurs of the spy business, I would warn that the book is short on the inner workings of our wonderful ASIO.

Comments powered by CComment