- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: From bushmen to businessmen

- Article Subtitle: Centrepage

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Bulletin, The Bulletin,

The journalistic Javelin,

The paper all the humor’s in

The paper every rumor’s in

The paper to inspire a grin

The Bulletin. The Bulletin.

(The Bulletin, 28 May 1887)

Though I’d been looking forward to this book I had doubts about reviewing it. By definition it must touch on personal loyalties and friendships, and then, too, I had preconceptions about Bulletin history.

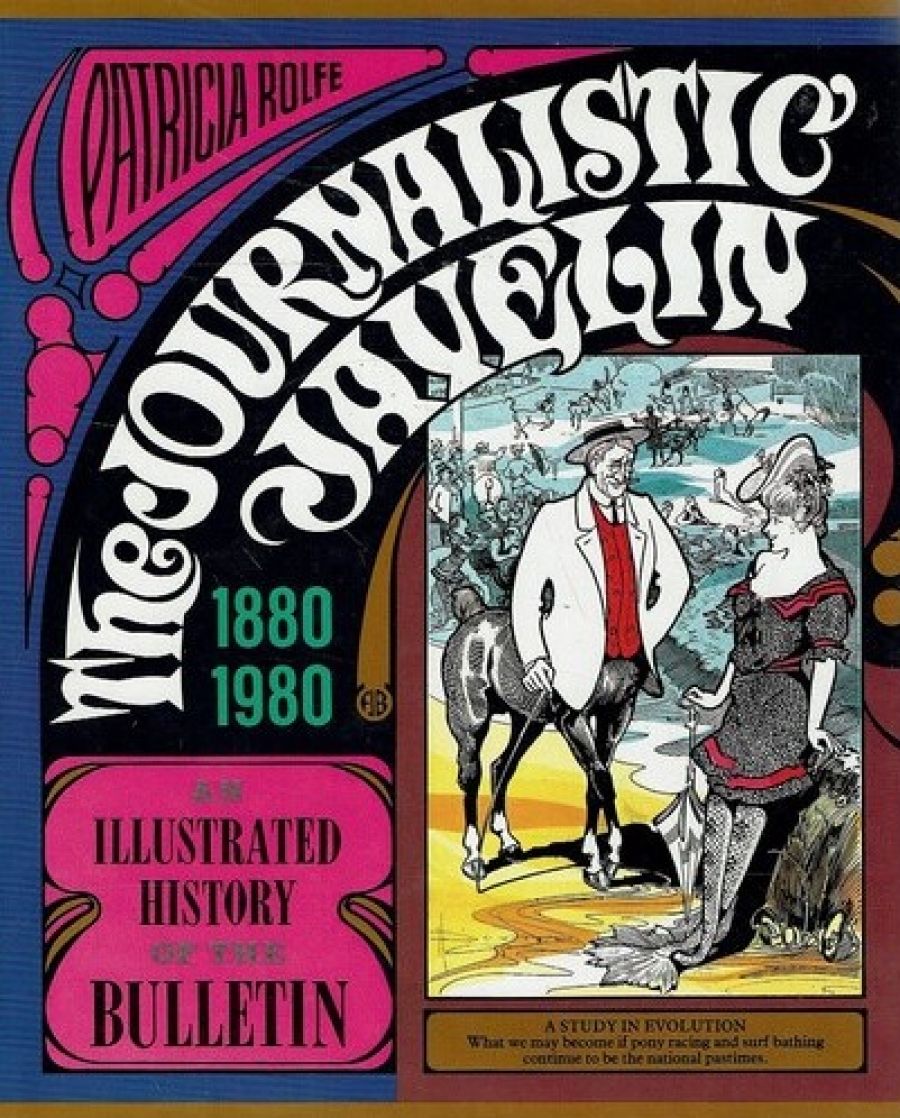

- Book 1 Title: The Journalistic Javelin

- Book 1 Subtitle: an illustrated history of the Bulletin

- Book 1 Biblio: Wildcat Press, $23.95, 315 pp

Some thirty years ago, dear Bill FitzHenry, to whose historical articles and research Patricia Rolfe generously acknowledges her debt, engineered my first real freelance ‘break’. Bill ought to have written a full-length history of the early Bulletin, and could have done so but, for various reasons, never did. Instead he suggested I might undertake the task with himself as mentor. So help me, in the utter ignorance, ambition, and confidence of youth I agreed.

I began systematic research, made, and still possess, copious notes and references, and established a fair idea of what I wanted to do. Fortunately Douglas Stewart accidentally foiled the scheme by suggesting I should also look out for bush ballads and songs for a collection. Balladry took over. The history was shelved. Mine would have been a very different book from this one, and much less good.

That is not false modesty. Patricia Rolfe has many necessary qualities I lacked: length and breadth of experience in journalism and newspaper management and, for the greater part of her history, no hampering personal involvement with the people she writes about either by direct acquaintance or at second hand. Only when she reaches the last thirty years or so years (and a history timed to appear during a centenary must come wholly up to date) is she constrained by necessary tact and all the difficulties of being too close to people and events. I therefore intend to ignore most of the last three of her twenty-four chapters which are worthy but not quite fair, and to concentrate on the twenty-one rich and rewarding sections.

Before that, though, I attempt to give some idea of the book as a whole, and must praise Frank Broadhurst’s splendid design. There are generous and appropriate illustrations to every page of text and then, dividing nearly every chapter from its successor, is a double page of cartoons and joke-blocks selected about a theme. Some of these spreads show examples from the earliest days to recent times. Others, like ‘Bush Missionary’ or ‘New Chum’ jests are social history capsules.

To avoid effects of starkness or monotony, many of the cartoons and joke-blocks have a sepia wash added to the original black line, sometimes to a whole of the drawing, sometimes to a part. Occasionally a grey wash unifies a page. The effect is magnificent and never more so than in the many examples of David Souter’s outstanding work. Broadhurst has also restored some drawings from the blemishes of age and crumbling paper – literally for certain of the earlier years powdering to dust. He tells me he wanted to present ‘not just a history, but to give present-day people an idea of the high standard of art produced in Australia at a time when, with the possible exception of Germany, this country produced the best drawings in black and white in the world’.

Patricia Rolfe ‘sees this as a book by a journalist about journalists – writers or artists – and, as such a labor of love’. It was not commissioned by Consolidated Press but researched and written in her own time and at her own expense.

Fittingly in a labour of love her towering and overwhelming love affair is with J. F. Archibald, a Bulletin founder and its longest serving editor, to whom Sydney owes a glorious fountain and the nation a major art prize. ‘No one has yet got Archibald down on paper in a substantial way’, she comments. Well, not until now, but the total of her words on him is substantial enough, and he comes to life in these pages in every important way.

R.D. FitzGerald once pointed out that many people do not really have a biography. He said ‘to be born, go to school, work for your living, marry, beget children, enjoy the common lot of man and eventually die, does not make biography. Archibald had a great deal more to his biography than that, and much that was tragic; but what affected his editorship, his general career, and other people who matter, is given here. The rest may be interesting, and some of it sensational, but not truly apposite. To explain what I mean differently: it has never seemed to me that the spicier aspects of Nelson’s affair with Emma Hamilton have much pertinence to his qualities of naval leadership and strategy, on the other hand Byron’s private, and not so private, life has essential bearing on his whole work.

One enjoyable feature of the book is Miss Rolfe’s own personality and point of view, expressed with felicity and displayed in quotation and illustration. Of the ‘optimism and energy’ of the 1890s she writes, ‘it was no golden age, but a time when the shell cracked and the native-born emerged’. Of Archibald: ‘He had imagination and passion, qualities so rare in journalism, in life, that many people seem unaware that they exist and perhaps would merely be discomforted if they discovered them.’ Sometimes she infuriates me but at least I feel I’m conducting my mental argument with a worthwhile adversary; for example of A.G. Stephens she observes: ‘His work bears little relation to literary criticism today. He is far from the polite gutting of books which earns a few dollars for freelance journalists and academics in the daily papers.’ I know what she means. I certainly suspect why she says it, why she sometimes protests far too much about other sensitive matters that touch on present Bulletin policies. I, for my part, will continue, politely, to pull out some more intestines, thereby earning my few dollars in the independent way I happen to prefer.

For every period of The Bulletin’s hundred years there are very funny anecdotes as witness Ronaid McCuaig saying he left the Sydney Morning Herald because he was afraid they were going to appoint prefects. There are very sad parts and one of them is the life of A.G. Stephens which with all its implications and gallant control, I find more dismal that the decline of Henry Lawson. Those implications are echoed by Will Dyson deploring what we now call the brain drain; after a brief illusory remission in the early 1970s his picture remains distressingly true: ‘The trouble with this country is its mental timidity. Physical courage – yes, I suppose it’s got its share of that perhaps a little more than its share, but put it face to face with a new idea and it goes all of a tremble.’

All the great figures are depicted and discussed: James Edmond, William MacLeod, Victor Daley (particularly well), Phil May, Low, Norman Lindsay, Henry Lawson, Cecil Mann, John Webb, David Adams, M.H. Ellis, etc. etc. etc., Douglas Stewart too, but he chiefly appears in those last three not-so-good chapters, and his major contribution as ‘Red Page’ editor is praised with faint damn. Most of the important writers of his time are named in passing or not at all.

Lesser figures also have generous mention my particular favourite ‘Scotty thee Wrinkler is remembered. So is John le Gay Brereton who was forced to stifle his anti-Boer War views in The Bulletin’s pages because to have spoken out might have cost him the university job he needed to support a family. Rolfe records that Chris Brennan, aware of Brereton’s bitter dilemma, dedicated The Burden of Tyre to him.

The Bulletin’s politics and its crusades are very fully and fairly covered – the admirable with the scatty. Side by side with the text the illustrations bring a hundred years most marvellously alive.

I indicated earlier my disinclination to argue points from the more recent material. Like the author this reviewer is too close to people, events, and assertions for adequate balance. Nor can I match her experience and knowledge of commercial journalism. The blame for a badly handled takeover exercise may be where she apportions it, it may be elsewhere, or capable of other interpretations. Certainly the magazine was ailing but whether the chosen cure was the only possible one in 1961, or whether other routines were considered, must be the province of some later historian. In fairness though I give one example of the kind of debate that the three last chapters may arouse.

As justification of the excision of short stories and poetry from the Bulletin’s pages (and this is mentioned elsewhere, and earlier, too), Patricia Rolfe says: ‘when time of staff and cost of postage are taken into account, it would probably cost as much as staffing a Canberra bureau … which would any editor today choose?’ She also pleads changed readership tastes and believes that creative writing is not missed by Bulletin readers. Obviously these are passionately disputable assertions. I avoid the passion but it is, I think, fair to suggest that newspapers like the Canberra Times, Sun News-Pictorial in Melbourne, and newspapers that occasionally carry Tabloid Story (they include the ‘new’ Bulletin) do use short fiction and make a selling point of it. The first two journals mentioned sponsor competitions that presumably avoid some of the costs and problems that Miss Rolfe discusses, and these events bring them great prestige and good will. They publish stories regularly.

That is one of the simpler issues. There are deeper and more complicated ones. To discover and ponder them will be one among many reasons for reading this enjoyable and important book.

Comments powered by CComment