- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Her previous work, A Patch of Blue, became a Hollywood film with Sidney Poitier, and another, Child of the Holocaust, was recently serialized by the ABC. Neither was short on social awareness, which makes her latest novel all the more inexplicable. All the characters of The Death of Ruth are stereotypical. The twists and nuances come in the plot, not in the characterization.

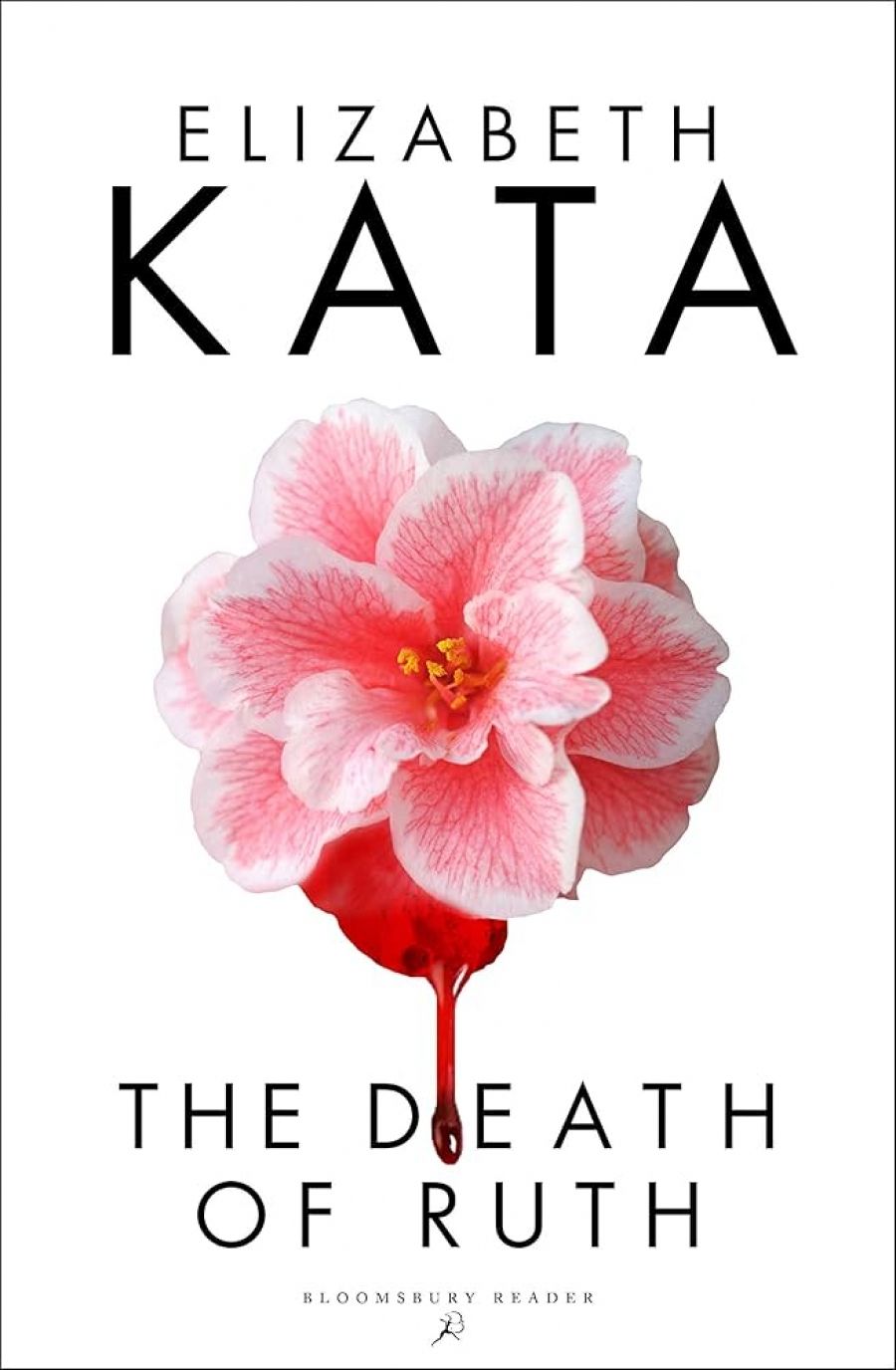

- Book 1 Title: The Death of Ruth

- Book 1 Biblio: Pan Books, $2.95 pb, 128pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Molly Blake, for instance, is a passive woman forever a bystander and recipient of other people’s actions. Her life is taken up with pleasing her husband and anticipating his needs. When she does commit an independent act of violence against her child-bashing neighbour, she spends four years of neurotic soulsearching which eventually leads to insanity and death. She is the ‘Angel in the House’ par excellence – the figure that Virginia Woolf wrote so passionately of as the main cause of the imprisonment of women. In her essay contained in the Women’s Press’s ‘Women and Writing’, Woolf writes: ‘Killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of a woman writer (because) ... had I not killed her she would have killed me . . . The future of fiction depends very much upon what extent men can be educated to stand free speech in women.’

In The Death of Ruth not only does the Angel in the House exist, but the neighbouring Ruth is the unfeminine aggressor who beats her children and even her husband. No reasons are given for her behaviour in allowing Damned Whores and God’s Police to live on mercilessly in Australian suburbia. There’s not even an attempt to give Ruth the background Jean Rhys belatedly gave to Mrs Rochester (Bertha Mason) in Wide Sargasso Sea.

Against these impossible stereotypes for women, Molly’s husband, John Blake and Inspector Grey, are humane integrated creatures – they’re compassionate, strong, self-motivated, and admirable role-models. The neighbour’s husband, Ralph, also seems all these things, but with an Agatha Christie twist of considerable ingenuity, it is revealed in the final pages that he is another kettle of fish entirely.

The main attempt of Elizabeth Kata to lessen the conventionality of her characters is to structure her novel through their different personae. The chapters are divided alternatively between the personae of husband and wife. The device works well thematically, but tends to grind the characters into their respective pigeon holes. Of course, Mills and Boon has never died and with Lady Diana’s recent emergence into public life complete with Barbara Cartland as her step-grandmother, it seems we may be in for a new spate of fiction that traps women more than ever. Reading The Death of Ruth made me realize again that writing today needs an enormous amount of homework. The treadmill of keeping informed can in some cases almost debilitate the actual writing process, but when a work of fiction springs from such awareness, as is the case of all non-fiction, then we have what is generally called ‘a work of art’. It remains perplexing to me how Elizabeth Kata could have turned from her previous writing to write this novel – it’s good read but on any other level it’s disappointing.

Comments powered by CComment