- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Bleak Spirit

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As she did so vividly in Tirra Lirra by the River, Jessica Anderson uses a returning expatriate woman to cast fresh eyes on the social and urban landscape of Australia. Here, it is Sylvia Foley who has spent some twenty years in Europe eschewing the comforts and constraints of suburban life, teaching Italian and conducting tours of the British Isles and the Continent. On a whim, she abandons her peripatetic life to return to Sydney for a few months prior to her plan to settle in Rome. Unbeknown to her, her autocratic father, Jack Cornock, is dying and she is immediately suspected by other members of her dislocated family of returning to benefit from the will – which she ultimately does as the recipient of her father’s vindictive gesture to spite his wife. And Sylvia’s ‘family’ is considerable. There is her illiterate mother Molly, now married to Ken, her brother Stewart, and her stepsiblings: Harry, Rosamond, Hermione, and Guy, the children of her father’s second wife, Greta.

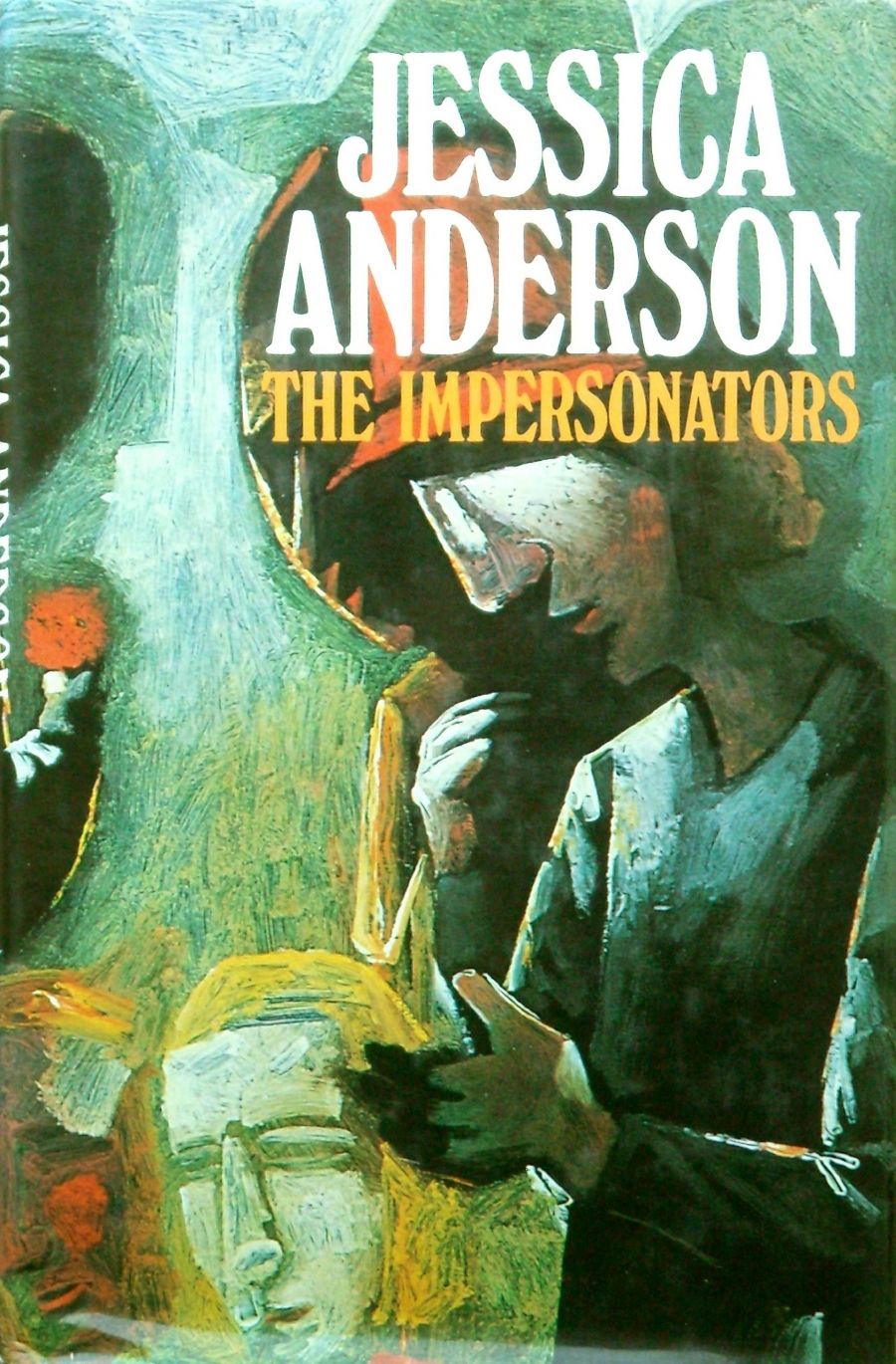

- Book 1 Title: The Impersonators

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $9.95, 252 pp, 0333299256

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Jessica Anderson is fascinated with the relationships in this family, which Sylvia succinctly images as ‘fractured ... cracked across and across’. This split familial structure is presided over by the brooding, paralysed patriarchal figure of Jack, stiffly garbed in his formal clothes of the 1920s, and whose terminal disability does nothing to mask his contempt for his stepchildren, his hatred of Greta. There is a kind of technical incest in the family, some bridges across the ‘fissures’; Harry and Sylvia fall in love and Hermione takes time out from her marriage to Steven to consider Stewart as a partner.

The dominant note in the book is one of insecurity – and it is superbly conveyed in a peculiarly Australian way. The fragility of the relationships, people’s personal insecurities, are mirrored in the tenuousness of real estate, or more specifically, in houses. That most Australian obsession, to own a home of one’s own, is manipulated in this novel to become a symbol of the temporary, the ephemeral. Underlying the witty and sharply observed detail of the Sydney topography of boxed and fenced houses, the ‘double-fronted brick bungalow’ and its image of stability, is a sliding morass of personal insecurity, of which the dominant image is Greta’s house. ‘The house that Jack built’, both as a family and a source of cohesion, is a crumbling edifice. He bequeaths it to Greta, deliberately depriving her of maintenance money so that she is forced at first to sell the furniture then ultimately the house, to live. Indeed, all the houses in this book are abandoned. Hermione and Steven are living in a flat in between houses, which Stewart, pragmatic real-estate salesman, is trying to sell them. Rosamond is forced to desert the house of her corporate crook husband (literally via a series of suburban fences), to live temporarily in the house of Greta before she too is obliged to sell. In fact, the only couple who show any solidity are Harry and Sylvia, who have always lived in rented flats and whose almost nomadic state is seen as a kind of permanence. At one point they are imaged in that most primitive and enduring home, a cave, as they shelter from the rain on a bushwalk. Guy, the self-indulgent youngest son of Greta, comments, chorus-like, on the action and observes at one stage ‘The quality of the shelter must decline,’ as indeed it seems it must if a relationship and people are to survive. It is as though Australia must demolish its false image of security in bricks-and-mortar if it is to show any maturity.

The Impersonators is a fascinating story of a family fractured and cracked, living in a continent similarly fractured and cracked, except for its peripheral cities whose very appearance of permanence belies the shifting tensions that lie beneath the solid brick veneer. Jessica Anderson portrays a desert, not so much the clichéd cultural wilderness of Australia per se, but a bleakness of human purpose and spirit which, of course, is the ultimate foundation of a society’s cultural strength or weakness.

Comments powered by CComment