- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Female Companions

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Palomino establishes Elizabeth Jolley as absolutely one of the best writers of fiction in this country, although it is a book that in some ways does not, I think, entirely resolve the problems it poses for itself. As I interpret Palomino one of the things Elizabeth Jolley intended to explore in her first novel, is the contrast between a person whose genes, hormones or whatever dictate that they shall for ever and irreversibly be homosexual; and a person whose sexual nature is capable of change and influence. She also pursues themes like this in some of her excellent short stories. The lovers in Palomino are Laura and Andrea, and it is Andrea’s excessive background that confuses the basic issues, a point I will return to.

- Book 1 Title: Palomino

- Book 1 Biblio: Outback Press, $12.95 pb, 260 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: The Travelling Entertainer and Other Stories

- Book 2 Biblio: Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 181 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

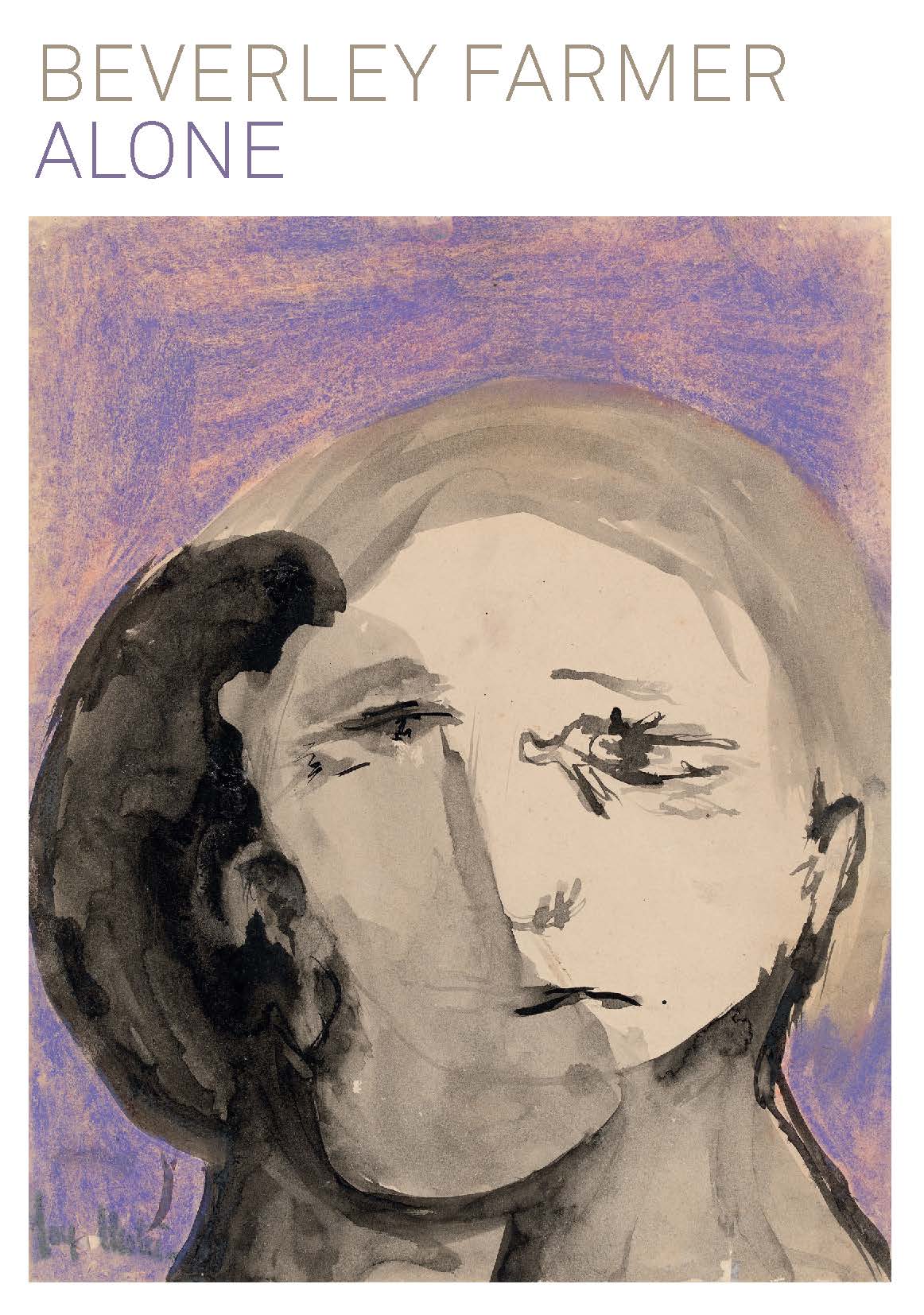

- Book 3 Title: Alone

- Book 3 Biblio: Sisters Publishing, 102 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

First though this book, and Beverley Farmer’s Alone, have made me for the umpteenth time ponder the hoary question of the extent to which in any given culture and era life is mirrored by fiction, or fiction itself alters life. For instance to judge by certain bodies of fiction some societies, and our own from time to time, have a great tolerance for, and admiration of, the merry prankster, who can be quite an evil fellow yet still greatly loved in story. He is seldom a figure of recent fiction. Does this mean something or nothing of significance?

When my father was a student of architecture in Australia, America and Europe (c. 1908-13) novels in English almost never so much as hinted as homosexuality and the community did not suspect it when impoverished young men shared cheap rooms in cities and steerage cabins on ships. Anxious parents (like my grandmother) were far more concerned about designing ladies of the pave, or that their Bohemian sons might (and many did) take to the bottle. According to my literary memory daughterly problems of the time were invariably heterosexual – and of course before the pill and other reliable contraceptives furtive love could have conspicuous consequences.

By my time in a comparable age-group (c. 1945-50) I, and my friends. University students, art-students, would-be writers, would-be’s ... viewed with sniggers and suspicion any two young men who shared a room or flat, or any never-married man over thirty-five. Australian fiction, partly because of censorship, partly perhaps because men who might have written it had died in World War 1, was sexually tepid and behind world trends in those days but the jokes that circulated reflected a fashionable preoccupation with male homosexuality and so did many black and white magazine cartoons. Maybe, and subtly, the stage was being prepared for community tolerance for the Gay Revolution, and the ‘comings out’ of some two decades later, because I do believe that what a community will tolerate depends essentially on what its middle aged people are prepared to tolerate.

Similarly, I think, with abortion. No matter how much anti-abortionists jump up and down in protest, the community has a fair tolerance for abortion reform these days precisely because, secretly, so many women of my age really did experience abortion during the war years and later, either in their own persons or in the persons of their friends. Sydney, and I’m sure other Australian cities, and well-known medical practitioners, chemist shops, and backyard practitioners and indeed abortion did enter Australian fiction by the 1950s, and even got past the censor which speaks volumes (pun intended) for altered community tolerance.

Not that honesty had been heard of. Very few homosexuals of either sex behaved indiscreetly in public (except at the Artists’ Ball when transvestites were traditionally immune from police and community harassment). Similarly heterosexual affairs were sedulously concealed. Girls who, in the parlance of the time ‘lived’ or ‘slept’ with a bloke usually did nothing of the sort. They lived with parents, or in rooms rented from fearsome landladies, and after an hour of love someone dressed in a hurry and snuck off by the last tram, train or bus. Australian fiction of the time seldom so much as suggests that middle class young people ever got further than a chaste kiss. Fiction about the working classes allowed itself to be more explicit – how odd in our allegedly classless society!

As for lesbians they were those teachers at school or several couples of long standing and great affection, but almost never ourselves. Nothing we read or heard put it into our heads that we might experiment. Jokes are an even better indicator than books for what engages the community mind, or is in the community air, and there were none about lesbians or incest. Then, in the 1950s subtly, suddenly, lesbian love and fraternal incest were rumoured about certain people and before you could say Jill Robinson lo! Mary McCarthy! Twenty years later, regular as clockwork, look what’s in our fiction, (and to the detriment of Palomino, I suggest). This brings me to Andrea’s background.

Andrea is probably a temporary lesbian in response to Laura’s kindness and her own problems. Theirs is a true, deep, deeply moving and doomed love affair but the structure of the book is determined by Andrea’s being weighed down with those sorts of coincidence that occur in life but are fiendishly difficult to make convincing in fiction. Andrea is not only passionately in love with her brother, who has grown away from her and married, but pregnant to him. Also their own mother ... beyond those dots I shan’t divulge the plot.

It would be easy to make the point that Jolley more effectively explores aspects of lesbian love in short stories like ‘Winter Nelis' and ‘Grasshoppers’ in The Travelling Entertainer, but that would be over-simple – they are of course sketchier than this long, dense novel. Andrea’s eventual refuge with women very different from Laura, and Laura’s own past tragedies, are all expressions of its central concern with what lesbian love is, can be, might be. There is, I think, a message too and not a happy one.

Nor, I must stress are homosexual characters the only ones in Elizabeth Jolley’s gallery. Her writing is splendid, her characters various, her humour delicious. She describes places, houses, occasions magnificently. By contrast with her wide-ranging assurance and accomplishment certain other more heralded and talked about women writers in this country look pretentious and thin. Local publishers are fortunate to have Jolley on their lists because when she publishes further afield, and she surely must and will, the Erica Jongs of this world can look to their laurels.

One measure of Beverley Farmer’s quality in her first novel, Alone, is that one can set it beside Palomino and not to its detriment. Shirley, the central character is exactly eighteen. Everything in her life is weighted against her, and every necessary clue from her past and present is cunningly introduced. She is born into a concerned, apparently unimaginative and very conventional Melbourne family and turns out to be a clever misfit with a passion for reading poetry and some talent for writing it. She is a misfit at school too. Her beautiful hair is her personal symbol and the only physical feature she acknowledges as desirable, though she often observes and comments on her body and is probably a not uncomely girl. She seems to lack any ability to respond to ordinary sexual arousal even at the hands of her adored Catherine and as she also rages, rants, postures and acts with conspicuous disregard for anyone else’s feelings Catherine, understandably, has walked out on her some time before the novel begins. Now Shirley dresses entirely in black.

During the months of their affair they acted, not to mince words, like silly little twits. Perhaps in an ideal world of beauty and poetry women might stroll at night beside the wharves and rivers of cities and wander beneath bridges and through parks suffering nothing worse than wet shoes while absorbing ineffable messages from nature and the starry universe. Well-intentioned police, to whom Shirley and Catherine are cheeky, think otherwise. Catherine gets herself raped. Shirley later, in her deserted despair, deliberately invites rape. She also witnesses, and tries to make poetic meaning from, a solitary masturbator and other unsavoury people and things.

Farmer leads her inexorably to her fate and writes so uncommonly well that, despite being impatient with Shirley, and despite being bored by her stereotype landlady, and also being distracted – though this is probably my own failing – by trying to work out what her psychiatric condition really was and how she might have been helped if anyone perceptive had happened to realise her dreadful problem – despite all this I could not abandon the sorry tale and expect great interest, in the future, from Beverley Farmer.

Comments powered by CComment