- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Uneasy Reading

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The men of the 2/30th Battalion laughingly enlisted. They didn't laugh on 16 February 1942 when, as part of the 8th Division and the Singapore garrison, they reluctantly surrendered to the Japanese. Happiness being relative, some of these Australians laughed all the way from Changi to a new camp near the wharves. Struggling to load bagged salt, they had no laughter, just helpless sickness in the stomach, as Sergeant Stan Arneil was savagely beaten by guards. Scenes change, states of mind go up and down, until the survivors are about to disembark in Sydney late in 1945: ‘and everybody on the ship is laughing all the time’.

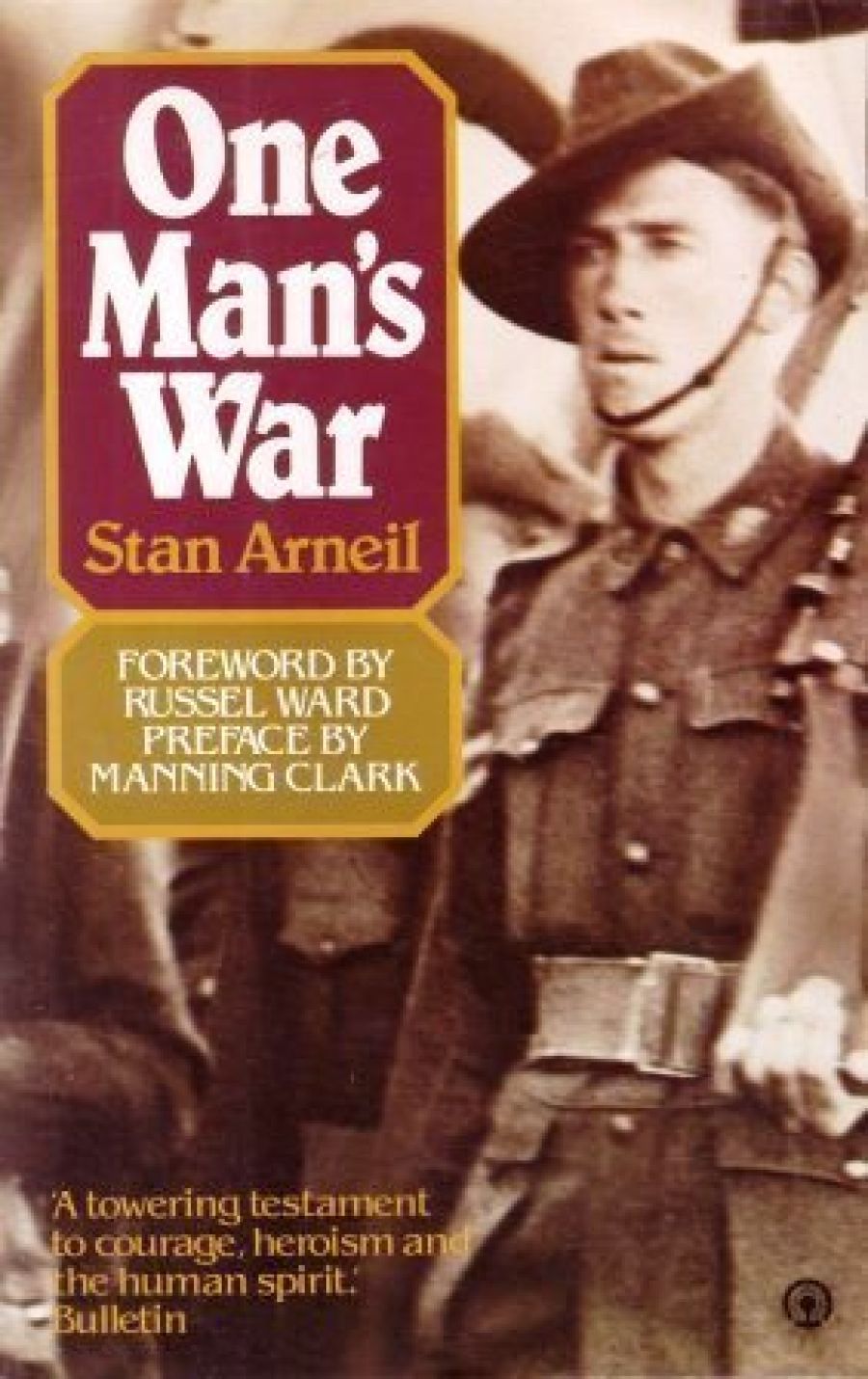

- Book 1 Title: One Man's War

- Book 1 Biblio: Alternative Publishing Co-operative, $19.95 pb, 288 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

A happy ending? In a way. But Arniel's P.O.W. diary, supplemented by commentary, notes and pictures, describes conditions and agony that can make a reader feel irrationally guilty over being fit, clean, comfortable and well fed. The diary is matter of fact, though keeping it was a feat in itself, and the explanatory material added for publication is notably restrained. Yet its pages still ooze and stink with suffering and death. They do not make happy reading.

One Man's War is a valuable record. Many of its photographs are a tribute to the Riverina motor mechanic G.H. Aspinall, who risked much in secretly taking them as a P.O.W. As in the official histories, nearly every Australian mentioned is identified and described in notes by Alex Dandie.

It's a shame that the book is physically unattractive, a strong but clumsy volume. Its dustjacket creaks on the covers like grandma’s corsets. The boards are about as heavy as those on the journal of Raffles's day that Arneil pinched from the wharves at Singapore. The whole is badly designed, crudely bound, crowded and jumbled, with unacceptable inconsistency in page lengths and type-spacing.

Another unfortunate decision was to print too many entries as facsimiles of the original diary. The result is disconcerting, and does not make for easier reading. (On p. 262, however, both a facsimile and a printed version are accidentally provided.)

Although a little editing was done – omitting some of the young man’s craving for food, food, food – more pruning would have made the diary more readable. How they pulled the wood trailer does not need describing on pp. 54, 56 and 59.

Perhaps the less a diary is tampered with the better, and this one has mostly been left alone. What, then, of the young man’s craving for sex? The diary is silent on how P.O.W.s coped with that side of their nature. Is it a sign of the time, the more inhibited 1940s? A sign of Arneil’s devout Catholicism? A sign of the grim situation: merely to survive was enough – and with scrotums red raw with dermatitis? It was ‘delicious’ to glimpse white women from Changi Gaol: ‘smiling, gay, neat and clean. They make a man ashamed that he has ever growled in his life’. Was that all? Well, he does admit to occasionally dreaming of Daisy Belle.

The Foreword (by Professor Russel Ward) and Introduction suggest that One Man's War explodes myths. Well ... it might surprise some people that most guards were Koreans, and that Changi was one of the better camps. Did Australian officers behave badly? Some criticisms of them in the diary are now admitted to be wrong. But the officers were not an unqualified ‘fine group of men’, Mr Arneil, and the evidence survives in your diary. Some were splendid, some ordinary and some unworthy of the name, as we might expect.

Life as a P.O.W. produced some happy times, and wonderful mateship? Most of us would expect that, too. Still, the diary’s most eloquent testimony is to the hellishness of existence: ‘I must live to get home. I must live, I repeat that ... I must live’.

Some Koreans and Japanese were decent, and – in places, at times – ‘life was about as pleasant ... as it ever can be for a prisoner-of-war’? That is not saying much. Professor Ward, and the old accounts of appalling Japanese brutality get more support from the diary than does any attempt to soften the ‘unrelieved hell’.

4 June 1943: ‘Men going down ... Three hundred and fifty men out to work today out of 2,000. He will never finish this railway, not with us anyway’. 10 June 1943: ‘God help the people who are causing us this agony’. 23 September 1943: ‘Men are dying for want of ... milk and butter’. 25 September 1943: ‘They have begun to amputate limbs because of ulcers: so I want to clear mine up ... Today a chap lay on a bamboo stretcher ... and had his arm amputated. The open latrines were twenty yards away and ... the flies ... The saw used for the amputation was ... used primarily to cut wood ...’ 20 August 1945: ‘The shame of these Red Cross stores is that they were ... received in Singapore in 1942 and the Japanese have denied them to us’. Decent, were they? Japanese prisoners in Australia were usually treated just like that, were they?

One Man's War makes no claim to being serious literature; it is unlike the trilogy by Ray Parkin. It is simply an annotated but artless diary, kept by an infantryman of great strength of character during years that were a greater test than many of us could pass. As such, it succeeds now as Arneil succeeded then.

Comments powered by CComment