- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Look in the Abyss

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This book must win the prize for the most lavish and the most amateurish book on an Australian artist. Not one of the 200 odd colour plates is dated; not even in the portentously titled Opus Index (a list of plates without page numbers!) do we get a single date or indication of present ownership. Where dates are given in the text, they are often vague and careless ‘... in the 1950s...’etc.

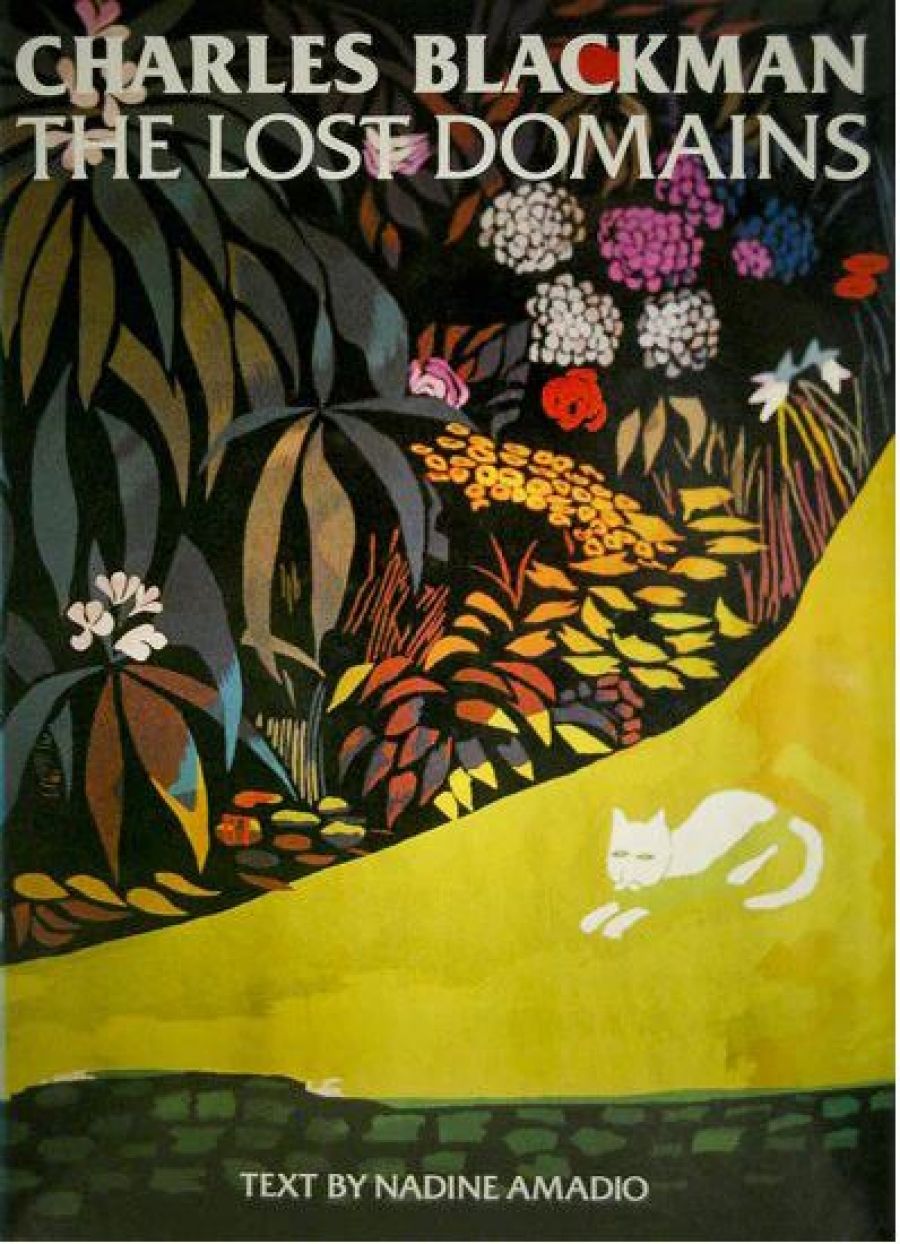

- Book 1 Title: Charles Blackman

- Book 1 Subtitle: The lost domains

- Book 1 Biblio: Reed, $100 hb, 144 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Once one steps outside the civilized fringes of Australia, the vast cruel wall of ancient dreams threatens to swamp the lonely psyche with its persuasive force. There is no protective sub-layer of culture here, no busy world of recent ghosts making a tidy pathway into the past as they do in Europe or the East.

or grossly sentimental and adulatory:

In an otherwise evasive age, his paintings sang with the form and discipline of love and agony, of wit and fantasy, of loneliness and death, and the awkward beauty of man. These images he could confront with a headlong passion and an uncompromising honesty.

It is hard to know whether such a dateless, invertebrate survey of Blackman's paintings is merely the result of incompetence or of design. Are we perhaps to think that Blackman's paintings are ‘timeless’ and that no matter whether early, middle or late they all dwell upon the same ‘lost domains’ of childhood, love, reverie and reading, for the text goes to some pains to show what a well-read chap Blackman is.

It’s one way of trying to put your artist beyond criticism. But in Blackman's case, it’s fatal and draws attention to the problem of his art. Blackman is that archetypal Australian romantic painter the wild, self-tutored phoenix. Early on he shows great promise, paints a memorable early series (Alice in Wonderland, 1956), engages with his contemporaries in the making of art history (Antipodean Exhibition and Manifesto, 1959), wins public recognition (Helena Rubinstein Travelling Scholarship, 1960) and achieves critical and commercial success through the 1960s with a smattering of international recognition. Then the fatal change sets in, to my eyes around 1967-8, borne on the wings of self-parody. He repeats, frequently on a bloated scale but with a smoothened touch, the images and perceptions of his earlier art. The vigorous turns to the perfumed; the inspired becomes the mechanical.

This book by deluxe misadventure gives the most devastating picture of the extent and rapidity of Blackman’s decline. The last chapter, ironically called Identities, dwells on his recreations of his favourite literary types - Colette, Proust, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. The writing, so wonky throughout, comes apart at the seams at this point; Colette seen ‘in her maturity her spirit forged and the wise and puckish face brimming with lost memories and deep awareness’. When that gets said – enough to make a schoolgirl blush in the 1980s – we are looking at high style commercial illustration, the kind of drawing Vogue used to publish every month. And those drawings and paintings tell us a lot about Blackman and his adulators.

They, and I reluctantly include the artist himself, mistakenly believe that the quality of Blackman’s art lies in its illustrative force; that what counts in Blackman above all else is the memorableness of the images. So for someone like the author of this book, the more sharply illustrative, the better. The colour plates in this book are so good and so plentiful that they contradict the text and hint at the real story. The remarkable quality of early Blackman derived from the way he combined direct painting, an instantaneity and spontaneity he learned in part from the Sidney Nolan he saw in John and Sunday Reed’s collection after he arrived in Melbourne in 1950, with an inborne feeling for the modelled, shaped and sculpted image. Blackman’s gifts worked best in drawings where tonal contrasts were sharp and in smaller paintings or large paintings divided into small parts like the Suites of 1959-60.

It was a gift whose fatal enemies were facility and rapidity. The direct, spontaneous painter needed to work over and up his images to bring them to concert pitch. On their own those big-eyed schoolgirls and tenebrous sleepers had no significance. Indeed, their propensity for sentimentality was a distinct liability. What a shame that both Blackman and his most recent amanuensis share the belief that thought and self-criticism are inimical to inspiration rather than inspiration’s handmaiden and handyman.

Comments powered by CComment