- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Power and the Culture

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Don’t judge Donald Horne’s books by their titles.

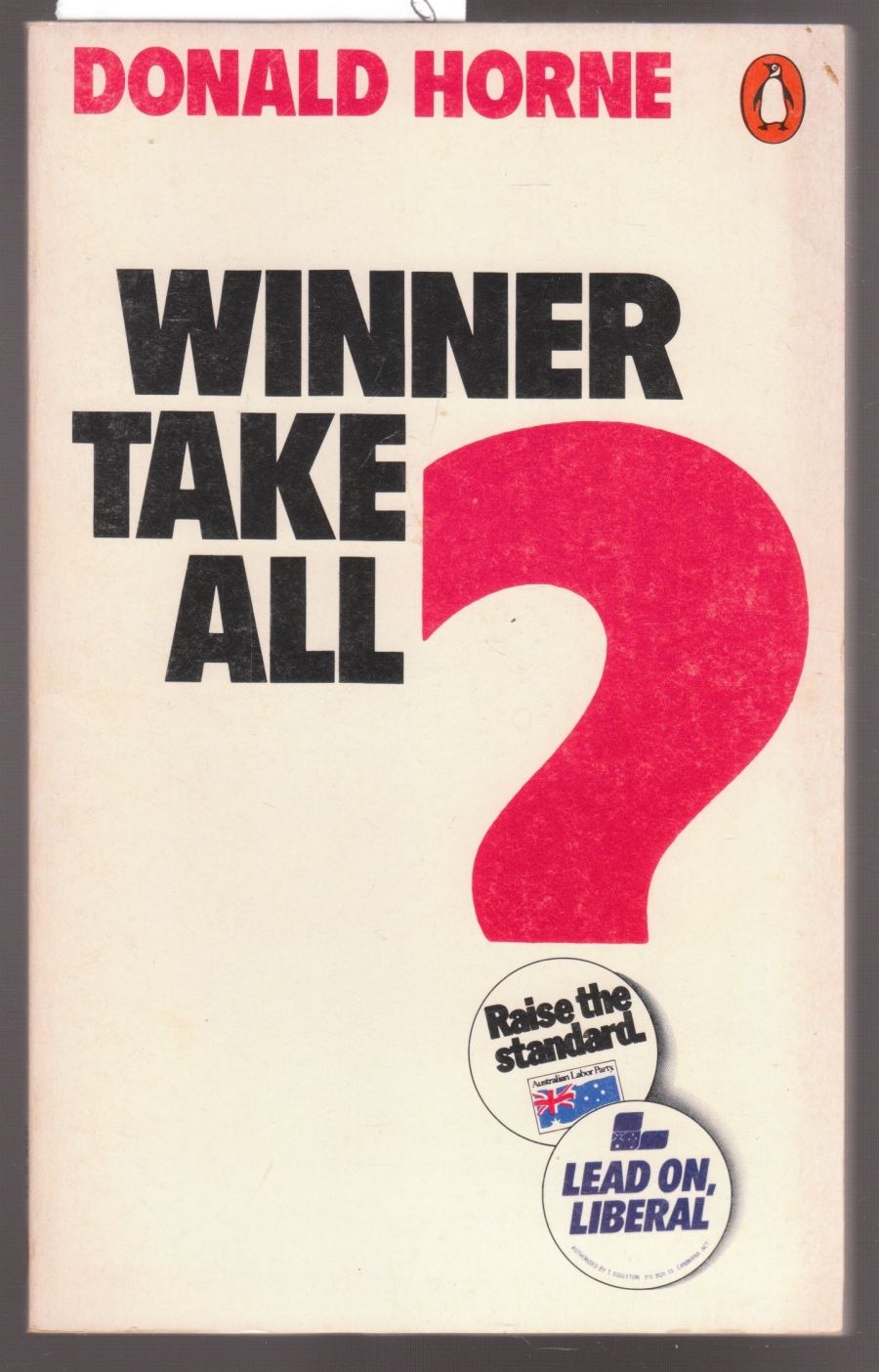

- Book 1 Title: Winner Take All?

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $2.95 pb, 132 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Winner Take All? is also a subplot. Despite the title of this Penguin original and the cover which depicts the slogans used by the Labor and Liberal parties during the 1980 election campaign, Horne’s latest book is only marginally concerned with that election and with the Australian electoral system. His real interest lies in the major issues facing Australians today (issues which were largely ignored by all parties in the 1980 election campaign) and in reasons why the Labor Party should immediately begin addressing these issues in preparation for the next election.

Horne says his line ‘is power and culture’. Winner Take AlI? is his sixth examination of these subjects as they relate to Australian society since the first of them, The Lucky Country, appeared in 1964. It’s a fairly slim volume, but the ten essays it contains get to the heart of the major economic and political problems facing Australia in the eighties.

Believing that Labor would win the 1980 election, Horne planned to call this new book Why Labor Won. Winner Take All? emerged as the title when it became apparent that not only had Labor lost, but also the party had twenty per cent fewer parliamentary seats than its opponents, despite the fact that it received only one per cent fewer of the total voters’ preferences. Winner take all, says Horne, rules the political game in Australia. In voting, in the powers of the houses of parliament, in interpreting the constitution, in the appointing and dismissing of governments, in statements about the powers of governments and heads of state and in the dissolving of parliaments, the generally accepted rule is the Roman one of woe to the conquered. Horne is so adamant on this issue that one wonders why he put the question mark in the title, Winner Take All?

Several of the essays were probably written before the election was held, and in the expectation of a Labor victory. Generally this does not matter, but it is a little disconcerting in the final essay, ‘The Sweden of the South?’, to read first of all how Labor might bring about democratic social change by following the example of the labour movement in Sweden, and then to be told that, a week and a half after the 1980 election, so disillusioned was the author he had concluded that it was ‘too late for a new Sweden’.

In the preface to his 1970 book, The Next Australia, Horne stated that the book was not ‘intended to settle issues but to raise them’. The same may be said of Winner Take All?, although here Horne does sometimes suggest solutions. Conservative readers might be outraged by some of the proposals. Others might find them a little simplistic. For Horne they are just the result of common sense and the belief in a fair go for all.

For example, he questions the Australian enthusiasm for ‘national development’ which both major political parties have pursued for its own sake. Linked with this is his anger at the softness of Australian politicians towards foreign investment. He asks us to imagine a not altogether imaginary case: A State government puts a large amount of money into power houses needed for an enormous increase in electricity generation to service foreign-controlled smelters. The government power houses get their coal from Australian mining companies mainly owned by foreigners, whose activities have already been subsidised by the national government in favourable tax schemes. The electricity authority then sells this electricity at cost (or less than cost) to the smelting plant, which has also been subsidised by favourable tax schemes. So who has gained? The answer is: the foreign shareholders.

As Horne also points out, many development schemes cannot even be supported by the argument that they create employment, for most of the major development operations are highly mechanised. Moreover, Horne claims that in some areas the creation of only one additional job may cost $500,000 or even $1,000,000 in capital investment. He does not give his source for this figure or for several other such statistics.

Horne wants us to begin asking questions about new development schemes. ‘Who would gain from this proposal? Whom might it harm?’ He wants governments to abandon the present financial incentives for low-employment foreign companies that provide little benefit to Australia, to tax their operations much more heavily than is done at present, and to establish government mineral searches, government mines and government processing plants. Labor, says Horne, must take a stronger stand on these issues, and it should constantly articulate its position to the people.

Horne also suggests that Labor needs a more positive policy on the issue of unemployment. He even argues that on this issue ‘the Swedish Employers’ Confederation seemed somewhat to the left of the public stance in the 1980 election of a cautious Australian Labor Party’. The majority of Australians, including many Labor supporters, are more concerned about ‘dole-bludging’ than about ‘tax-bludging’. For Horne this callous attitude towards the unemployed marks the end of the Australian tradition of mateship.

But he sees some hope for improvement if the Labor Party returns to the quality-of-life programs that were characteristic of the Whitlam years. His suggestions here are radical, but again Horne sees them as commonsensical: higher taxes on high-productivity industries that provide little employment; subsidisation of low-productivity labour-intensive quality-of-life programmes; transference of public financial support for extensive but non-economic traditional industries to such areas as cultural resources centres or alternative lifestyle communes.

We should not be hypnotised by the word ‘work’ as if paid labour were an end in itself. If the ends we are seeking are those of human dignity, human welfare and recognition of the human potential, we need another word for work. Instead of ‘job-creation programmes’, we need programmes to enlarge human dignity and human welfare.

At first it appears that the chapter in this book on the Canberra press gallery is an anomaly. How does it relate to the theme of a new role for Labor and the important social and political issues that must be confronted? But it soon becomes clear that the changes in Australian society Horne would like to see depend on an informed public. And, partly because of the procedures of the Canberra press gallery, the Australian public is not well informed about political matters. ‘Avoidance of issues’, says Horne, ‘is institutionalised into the work patterns and norms of the press gallery … National journalists have been among the most important agents for trivialising politics in Australia’.

Horne suggests several reasons for this appalling state of affairs. For a start there are no regular, full-time generalist national affairs commentators on any of the Australian newspapers or magazines. But most important is the widely accepted notion that national news and national comment is limited to what happens in Canberra, generally only to that which occurs in parliament house itself. Because their attention is directed so closely on the frequently trivial happenings within parliament house, members of the national press gallery rarely are able to report on the major issues, and are not well enough informed to define ‘the conflicts and the changing demands in society’ and to contemplate action about them.

Horne returns to this theme in his final chapter the one in which he concludes that it is ‘too late for a new Sweden’ That conclusion seems to have been partly influenced by his depression after talking at the National Press Club in Canberra. He says that many of the questions he was asked were designed to let him know how wrong he was in thinking parliament house was not the centre of everything. If some of the nation’s top political journalists could not or would not focus their attention on the real issues in society, Horne reflects that ‘it might be unreal to expect anything much from conventional political parties, or to look towards them at all’.

But that lapse into pessimism is not symptomatic of the book as a whole. Certainly he writes gloomily about lack of progress in such things as the treatment of Aborigines, especially in the banana republics of Queensland and Western Australia, whose rulers he sees as ‘the principal forces of illiberalism and philistinism in Australia’. But he does detect signs of changing attitudes in other areas of concern. Multiculturalism has now become a national ideal; the ‘new class’ of non-owners who hold most positions of authority in Australia might very well approve of programs which look more realistically at Australian society; that is at those issues Horne addresses in this book. Horne sees hope for the future in this new class, which includes technocrats, professionals, teachers, promoters, artists, intellectuals, performers, publicists, and even students.

Clearly, the medium through which changes will come about in attitudes and policies related to the important issues of work, development, foreign capital, foreign and defence policy, the media, electoral reform, etc. will be, in Horne’s view, a revitalised Labor Party, able to draw confidence from the size of its total vote in the 1980 election. But the real changes must come from the people.

If attitudes are to change in a society it must happen through complex interchanges among the people themselves, doing this in their own ways and in their own languages and with their own methods although perhaps with crystallisation and other promptings from various kinds of publicists, as well as from leaders among the people themselves.

Horne himself is Australia’s most important such publicist, and the country has been fortunate in having, since 1964 at least, a publicist as discerning, as articulate and as controversial as he has been. It is just possible that the promptings he makes in Winner Take All? might encourage changed attitudes in our society.

Comments powered by CComment