- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

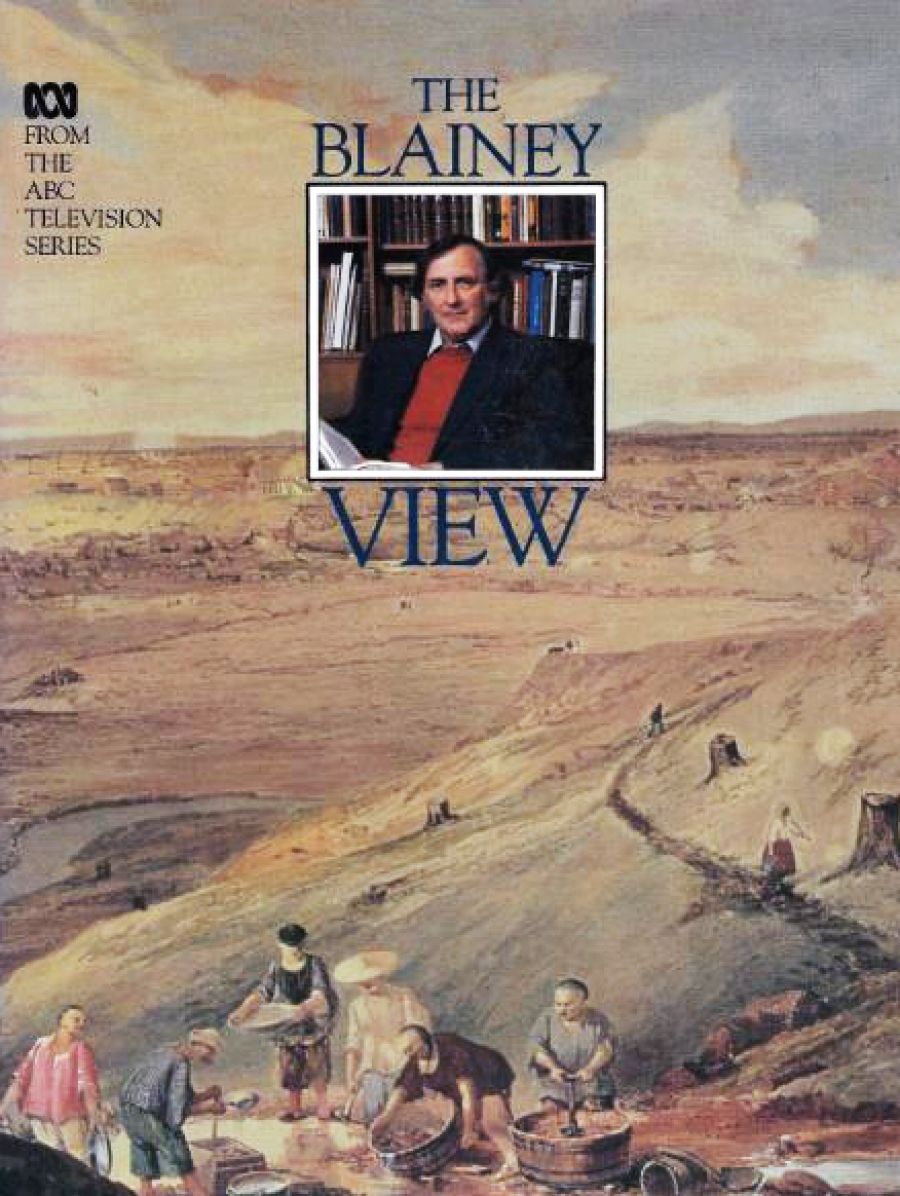

Geoffrey Blainey must be Australia’s bestselling historian by a very long way. His audience is far wider than Manning Clark’s for instance: and far less critical. Clark is periodically savaged by packs so frenzied they often seem unable to recognise the nature of the quarry. The difference of course is a matter of both style and substance. Clark, as an early critic once said, is ‘full of great oaths and bearded like the pard’, and he has not changed his fundamental spots. Blainey’s picture is inserted in the barren landscape on the front cover of this book, all warm and friendly; not a Jeremiah, but a kindly tribal elder who will unravel your historical landscape sotto voce, and with perfect equanimity. You can step into your past with Geoffrey Blainey and know you’ll be safe. He’s just about the friendliest historian imaginable.

- Book 1 Title: The Blainey View

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan/ABC, 155 pp, $22.50 hb

That common touch also pervades the television series, but almost self-consciously so. The professor fossicks around the historical landscape like any digger, except he knows where the relics are. Not a toff, but Graham Kennedy, provides the commentary, but he speaks at a measured bedtime story pace and seems compelled to round his vowels for the ABC. When the producers seem to get their way, and Blainey finds himself gingerly crossing South East Asia on a studio floor map, he looks about as comfortable as Robert Hughes in a cowshed. Blainey’s style is too democratic for television – it’s not folksy, not macho, not kinky.

But there is a problem with this book (which no doubt will be sold by the hundredweight) not deriving from either presentation or subject matter, but seemingly from pitch. Sometimes in the search for Everyman, Blainey seems to have found twelve-year-olds. And he becomes a very patronising elder. We are told that the Depression was ‘really a reluctance to spend’. We are told very little else about its causes; but we are told that it continued until the ‘house needed a new roof, the children wanted new shoes, the bicycle had broken down’, and our miserly mums and dads coughed up out of their savings. Out of the political agonisings, machinations, and deceits of the day, Blainey draws only the conclusion that ‘most Australians preferred unemployment to the loss of individual freedom, to the loss of a few privileges, to the loss of a little icing on the cake, to the loss of their ideology’. No one could agree on how to share the sacrifice he says. True enough. But there was also a debate about how to share the wealth.

The text contains a good deal of patronising populism. It takes Paul McGowan, ‘a farming consultant who lives in the district and has given agricultural advice to governments as far apart as China and East Africa’, to tell us that the soil in Kelly country was poor in Ned’s day, and to deduce from the old slab sheds that the trees thereabouts had been big. Gristly old codgers wander in and out of the text with reminiscences. It’s nice to meet them; but it would be nicer still to be offered a bit of the gristle of Anglo-Australian relationships (not to say sexual relationships), Australian racism, Australian religion (which surely helps to explain the inexplicable deeds Blainey describes), or Australian capitalism. Blainey must have considered it too tough for the general audience.

Something has gone wrong in the prose. In writing ‘down’ the text is often reduced to fatuousness and prolixity. A discussion of the tyranny of distance leads to the remark that the ‘length of the voyage, and the uncertainty about when the ship would reach an Australian port, were unavoidable’. Australia’s relationship with Britain before 1938 is judged to be successful largely on the grounds that there were ‘surprisingly few tensions and quarrels’. But surely it fell down in 1938 precisely because there had been ‘few tensions and quarrels’.

There is a Panglossian character to The Blainey View that hides the significance of many of his ideas and puts exploration of central and contentious issues in the country’s development out of bounds. A novice might come away feeling that he has learnt many things but not the one big thing, albeit there would seem to be a good chance that sooner or later something will be invented to get rid of the problem altogether.

There are of course some brilliant photographs: Max Dupain’s Depression studies; a hair-raising portrait of a Tasmanian woodchopper in full swing; the famous ones of Isaac Isaacs in governor-general’s regalia and looking like the product of a union between Daisy Bates and a Kadaitcha man.

But the TV’s better, for all its faults – if only because you can hear that Anglicised voice on the newsreel telling Australians that Singapore is impregnable and the Wirraway is just the greatest thing in the air.

Comments powered by CComment