- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Language

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

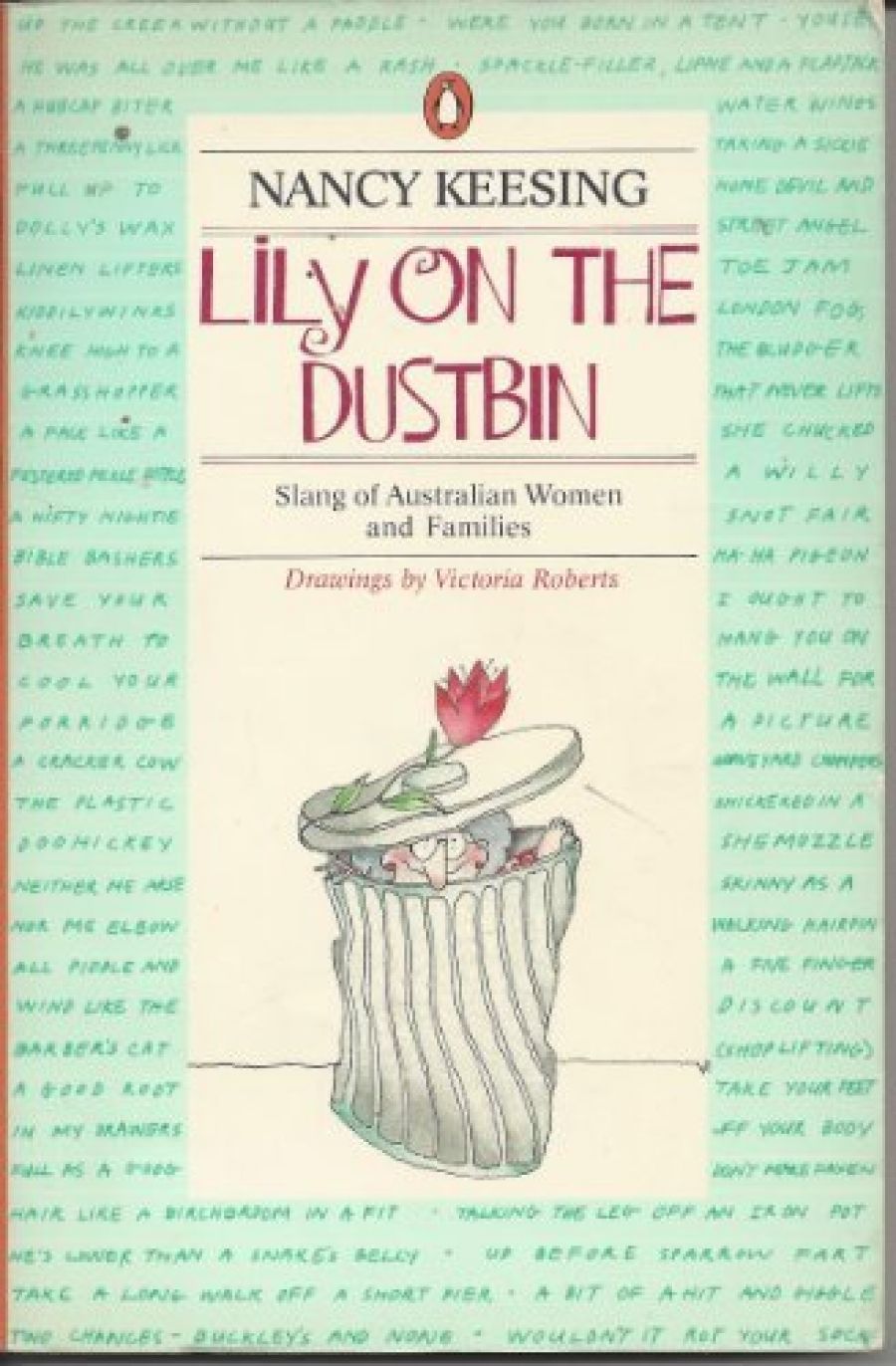

Do you know the meaning of (or do you use?) ‘white leghorn day’, ‘five finger discount’, ‘beating the gun with an APC’? When a woman ‘chucks a bridge’ what is she doing? Have you come across ‘scarce as rocking-horse shit’, or ‘easy as pee-the-bed-awake’ or ‘tight as a fish’s bum and that’s watertight’ or ‘The streets are full of sailors and not a whore in the house has been washed’? These expressions and plenty more are discussed in Nancy Keesing’s Lily on the Dustbin. Slang of Australian women and families.

- Book 1 Title: Lily on the Dustbin

- Book 1 Subtitle: Slang of Australian women and families

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 188 pp, $5.95 pb

Like any other pioneer, Keesing runs into many difficulties. Some of these will presumably be solved in an expanded second edition. One of the main ones is adumbrated in the subtitle, ‘Slang of Australian women and families’. ‘Families’ in this context raises the spectre of males. There is a valid distinction to be made, of course, between family usage, women’s usage, men’s usage. There is also a neutral ground which may be simply ‘adult’ and ‘child’ language. It seems to me that Keesing does not push hard enough at her idea – an important one – of women’s language and that much of the collection belongs to that giant species, ‘ordinary Australian’. I am not convinced that more women than men end their sentences with ‘but’. I am not convinced that ‘bangs like a lavvy (dunny) door in a gale’ is properly represented by either of those Americanised terms ‘Sheilaspeak’ or ‘Familyspeak’. And I have heard a number of men use the term ‘to spend a penny’ even if their usage pays no heed to the fact that urinals are free while cubicles cost. These examples might seem quibbles, but they do point to the fact that this collection has not resolved its own terms of reference. Perhaps it could be considered to be a collection of family usage. In Keesing’s terms of reference, males join the family only by invitation and on sufferance. In the course of the collection they are there rather insistently often.

I have two other difficulties with this book. The first is that all expressions are given an equal, neutral rating, without discussion of origin, frequency, and current usage. The use of oral sources suggests ‘living language’ but I suspect that many of Keesing’s correspondents are engaged in nostalgia. It is important that these sayings are recorded but their recording is also their in memoriam notice, as with an expression such as ‘flypaper for a nosy stickybeak’. Keesing places great trust in her source’s memories and records as facts stories that have long become jokes. I suspect that the Irish born solicitor was indulging in blarney when recalling a shit-urine story that happened in Sydney in 1948. In a slightly altered form, it was one of the first Irish jokes I ever heard. And I wouldn’t be surprised to find that ‘what do you do with year pants when your wear them out’ joke (‘wear them home again if l can find them’) was found in older cultures.

My other reservation is about the structure of the book. The sayings are linked by an exposition that often strains under the effort. Sometimes it sounds a little like ‘Mummy is in the kitchen peeling the taties’ in an ‘I can read’ series. Part of the problem is that many colloquialisms are cliches, and many are boring, especially when thrown against their rivals or alternatives out of context.

In spite of these reservations, this is an important and interesting collection. It raises many linguistic questions and is a book that is socially alert. It has some engaging and memorable discussions. Keesing is at her best when elaborating rather than attempting to string expressions together. I loved the discussion of Vegemite and of the expression ‘a wigwam for a goose’s bridle’. (The second half that was used when adults were telling me to mind my own business was ‘and a pony saddle (or headstall) to fit a duck’ which suggests that my elders at least focused more on horses than on brides, which is different from the experience of a number of Keesing’s correspondents.) This is a genuinely pioneering work that is informative, sometimes entertaining, often funny. And sometimes boring. And much better for dipping into rather than reading consecutively. I leave you with two more of my delights.

A footnote on the discussion of terms for menstruation reads: ‘Possibly deriving from Tennyson: “The curse is come upon me, cried the Lady of Shallot”’. And I bet you don’t know what ‘toe jam’ is. I do. Now.

Comments powered by CComment