- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In Dove, the familiar Barbara Hanrahan ingredients – acute realism and the fantastic, the grotesque – are combined once again to produce yet another powerful and moving novel. The scale of realism and fantasy is, as always, finely balanced. The various locations of the novel, for instance, are beautifully realised. Hanrahan has the eye of the graphic artist for the broad canvas, the sweep of light and sky, and the telling detail. Her eye ranges from the Adelaide Hills to the suburbs of ‘pebble dash and pittosporum’ to the Mallee: ‘an antipodean jungle of stiff splintered branches, a mysterious pearly-grey gloom’ interspersed with the ‘faraway rash of green’ that is the wheat. Yet there is more to landscape than this; place is used throughout to evoke psychic states. Appleton, for instance, suggests beatitude and primal innocence. Arden Valley the fairytale potential for the transformation of life, and the Mallee the promised land of plenteous crops and realised love.

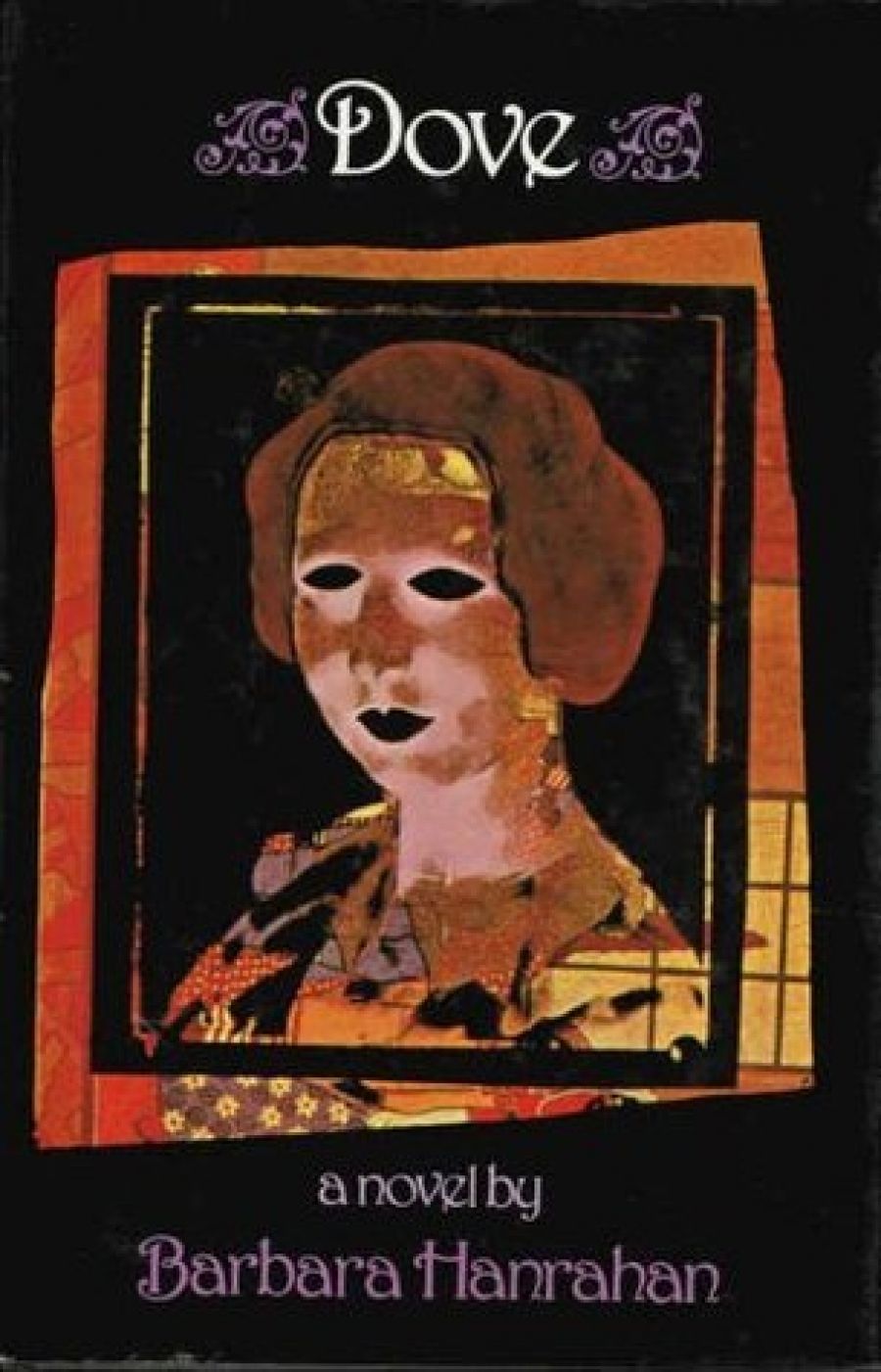

- Book 1 Title: Dove

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, 203 p., $12.95, $7.95 pb.

As well, however, landscape projects the dualism – the antithesis of good and evil – that is at the heart of the book. In these terms, Appleton is a place of rotting fruit and decay, of the stench of lavatory creeper and stink weed, while Arden Valley is not only ‘a green leafy place where Lady’s Fingers and Black Emperors dangled’ for ‘at vintage time the grape juice dripped from laden waggons like blood’. The Mallee, too, denies its promise; it becomes a place of aridity and the death of love, of the poison cart and the rotting carcases of rabbits. Its most fitting symbol is the gruesome tablecloth of snakeskins sewn together, their tails ‘radiating from one snake coiled up in the middle, the pendant heads forming a fringe’.

The delicate balance between these dual aspects – the realistic and the fantastic – is preserved in the characterisation. Hanrahan has a faultless eye for suggestive detail and the many minor characters are perhaps the most evocative. Sister Moira is an example:

The pebble-lenses of her spectacles had been polished to a blinding brilliance; her wimple whispered scratchily, her habit was shifty with shadow … She was the nun who always held her rosary beads when she walked so they wouldn’t hear her coming.

The major characters are more stereotyped for this is, after all, a world of fantasy and melodrama. The male figures are evil, grotesque, stupid or ineffective (as are some of the females) but the main female characters – Crystal, Dove, and Clare – are strong, imbued with a sense of heroism, of ‘personal legend’. They act and suffer in an ambivalent world, at the mercy of feckless or evil fathers, conniving older women and exploiters of many kinds.

The omnipresence of evil is emphasised by the way in which the narrator moves through the consciousness of three girl-children, helpless and vulnerable and pitted against manipulating elders, yet heroic and ultimately triumphant as, for instance, when the child Crystal snatches the baby Dove from the appropriating Mrs Arden, or when Clare survives the destruction of Arden House.

The child’s-eye view allows full play to elements of fantasy – a magic castle, a witch-like fairy godmother, a lost child identified by a coral necklace, a seemingly benevolent rescuer who transforms Dove to a tame canary in an aviary of captive birds – and it is through these that both the promise and the ultimate horror of life are defined. Victorian stereotypes of morbidity, death and the trappings of death further define this as a world of menace, imaged in rotten fruit, dead babies and failed and frustrated lives. The novel opens with a funeral (and the cryptic comment ‘For once life was stirring’) and concludes with an apocalyptic fire which destroys Arden House and the evil it embodies and provides us with yet one more of those great set pieces of grotesquerie for which Hanrahan’s works are justifiably celebrated.

The novel then is one further example of that special quality that we associate with Hanrahan’s works: fantasy and melodrama played out against an acute realism of place and detail, the whole charged with an apocalyptic sense of good and evil. It’s an effective formula which has worked well in the past, but it will not, in my opinion, bear further repetition. Hanrahan should perhaps take note of Jean Cocteau’s warning:

A good writer always strikes in the same place, but each time with a hammer of a different size and substance … If he always used the same hammer, he would end by smashing the nail head, driving nothing in, and merely making an empty noise.

Comments powered by CComment