- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

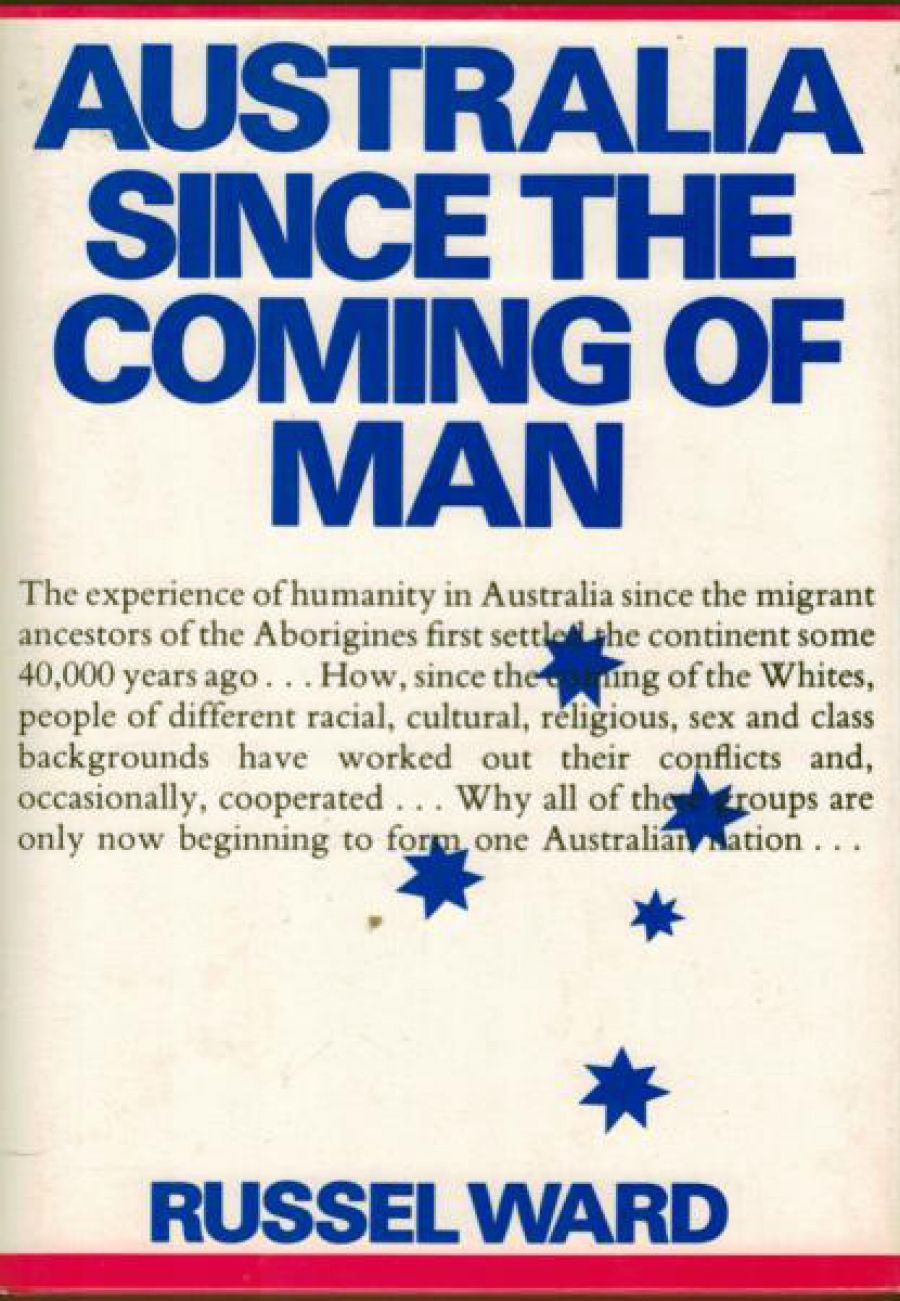

Russel Ward’s new book is a revision of History, which he published in 1965, mainly for an American audience. In fact, it was read more in Australia and now he has extended the work, put in more detail, and, presumably in response to recent developments, included some cursory glances at the doings of Aborigines, explorers, and the female half of the Australian people.

- Book 1 Title: Australia Since the Coming of Man

- Book 1 Biblio: Lansdowne Press, illus., index, 254 p., $20

- Book 2 Title: New History

- Book 2 Subtitle: Studying Australia today

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, 216 p., $19.95 hb, $9.95 pb

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2020/November/Meta/51tBLs7cS4L.jpg

In addition, the author testifies that he does not latter himself he has been able to stifle or disguise his own biases. But does not ‘bias’ imply ‘nonbiased’ or, strictly speaking, an inert position? I think ‘bias’ is a misleading word.

A further statement that the author hates in particular those conservatives who smash constitutional traditions instead of jealously guarding them, tells us a good deal more about Professor Ward than it does about those he so thoroughly despises. But does he really believe that there was ever in Australia any real group of ‘conservatives’, in political power, who jealously guarded constitutional traditions when it did not suit them to do so? And what serious ‘constitutional traditions’, for god’s sake? The reader will find in the final chapter (Reform and Reaction. c.1967–82) what he by now strongly suspects: the author’s outrage at what happened to a mildly reformist party between 1972 and 1975 and, though he does not say it explicitly. the shock to the author’s creditable assumptions when not one of his ‘conservatives’ had enough principle to resign from the parties which made Labor government unworkable. One doubts whether the author has really fully appreciated the point that the Free Trade Act of 1901, sailing under the curious colours of a ‘constitution’, does not permit Labor policy ever fully to be implemented anywhere in Australian society.

This book is extremely well illustrated, reads generally well, but is surprisingly unadventurous in its lack of strong overview (except in the final section perhaps), despite the author’s statements of principle about being for the poor and the weak and the exploited, and opposed to the strong and the ruthless. I suppose this is because he feels that, in a general history, certain events and set-pieces must willy-nilly make their appearance – the Eureka Stockade, free, secular and compulsory education, and so on. It should be said, however, that the section on the first human occupation of the continent is innovatory in that Ward brings together the now extensive material on prehistory and early exploration, and correctly concludes that each fresh discovery of Aboriginal settlement raises many more questions than it answers.

I am not sure the redrawn Dauphin map should so unreservedly be accepted as revealing detailed Portuguese charting of the eastern Australian coast (though it is extremely likely that the Portuguese had some knowledge of north-western part of Australia), and the the Mahogany Ship and La Trobe’s famous Keys have yet been elevated to the status of certain facts. Still, the 1578 illustration of a marsupial on the title page of Speculum Orbis Terrae is interesting and indeed suggests the likelihood that the artist had heard of, or read, a description of a kangaroo or wallaby. And yet … the creature has no tail, and surely an appendage as noticeable as that would have figured in an illustration? Oh well, perhaps not.

This book then proceeds predictably for a History of Australia: Black and White Discoverers; Empire, Convicts and Currency; New Settlements and New Pastures; Diggers, Democracy and Urbanization; Radicals and Nationalists; War and Depression; War and Affluence; Reform and Reaction. There is in the text a curious schoolmasterish, didactic style which will not be to the taste of some: the ‘Yet we should notice that …’ and ‘We shall now glance at’ sort of thing. Few will quarrel with an idiosyncrasy of style, however, and the general balance is sound, with the most memorable parts of the work residing not only in the striking visual material but in the many apt verbal illustrations of a point. For instance, the Hon. David Carnegie in 1896, in Western Australia, found water during his aristocratic explorations simply by kidnapping a member of a desert Aboriginal tribe and keeping him or her prisoner without water until the noble gentleman’s party was led to a well.

The book from 190l perforce mirrors the author’s A Nation for a Continent (1980) and stresses how in the period after the Great War, the fire went out of the vision which had inspired so many of the previous generation. The Jazz Age, the Depression and the war of 1939–45 are traversed neatly and the boom, years of the Menzies era given proper attention.

There are a few factual slips; the Molesworth Committee had little to do with the decision to end the assignment; W.M. Hughes, who claimed he was born in Wales in 1864, was lying on both counts; the sketch on page 78 of boundary changes is misleading in that it shows Van Diemen’s Land coming into existence as a separate colony in 1859 instead of 1825.

Given Ward’s warning in his Introduction about his interest in the fate, and fortune of the meek who certainly have not inherited the earth in Australia, I looked for strenuous analysis in the final section of the book at least, and there is an intriguing and angry use of damning evidence in relation to the Petrov affair. Ward concludes warmly that there was a plot by a gang of malignant conspirators who sweated with fear at the prospect of the people daring to elect a Labor administration in 1954. and took active steps to prevent such an appalling thing. Now, I wonder what destructive skill such traitors would have employed if Labor had indeed won, as in 1972? Doesn’t bear thinking about, does it?

On the whole, I am prepared to say, this book does not really carry through a sufficiently coherent overview, despite the author’s testimony and those events in his career which exhibit how ridiculous it is to suppose that ‘fairness’ and ‘objectivity’ play a part in right-wing Australian political life when the chips are down. The concept of colonialism and exploitation would probably have been a fruitful theme.

We now look forward to a bean spiller. How about from Russel Ward something along the lines of ‘Truth no Longer a Stranger; or, My Life and Times, in which is incorporated, without Fear or Favour, some Observations on allegedly True Histories of These Colonies’? Now, that would be something.

Professor Ward also figures in Osborne and Mandie’s book, largely in a lucidly and vigorously argued section by John Merritt on Labour History, the New Left and so on, where Ward’s Australian Legend came under heavy attack by the New Whippersnappers, as he probably felt like calling them, equipped with all the insight of hindsight. In this book, twelve authors go forth to report on work done in certain new fields, and the ideology and historiography involved, with signposts towards future roads of research. The twelve are not exactly voyaging yet on utterly strange seas of thought and really great interest or surprise: their contributions are on the history of Aborigines, Women, Oral Sources, Medicine, Sport, Immigration, Labour, New Guinea, Communication, and Urban Life.

The reader will find a thousand new ideas for research and will come away from perusing these chapters by different hands with an excellent knowledge of the state of play and, it should be stressed, more than a little feeling of excitement at what is in store for. the reader if all these paths are ventured upon. What does emerge actually is the generally unadventurous character of much historical writing in Australia till recently, that is, if you believe that adventurousness itself is a virtue in this field. New History is a great shot in the arm for all who feel weary and ill at ease or simply jaundiced and jaded but mainlining is fraught with enormous danger. That danger is the prospect of removal totally from the field of action because there is the real prospect of triviality in some of the areas.

Mandie himself is quick to recognise this in the case of sport. The problem is the usual one in areas related to social history: what is real is not always what is historically significant, unless of course one is deceived into believing, within the same framework, the Newspeak that the insignificant is significant.

Comments powered by CComment