- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

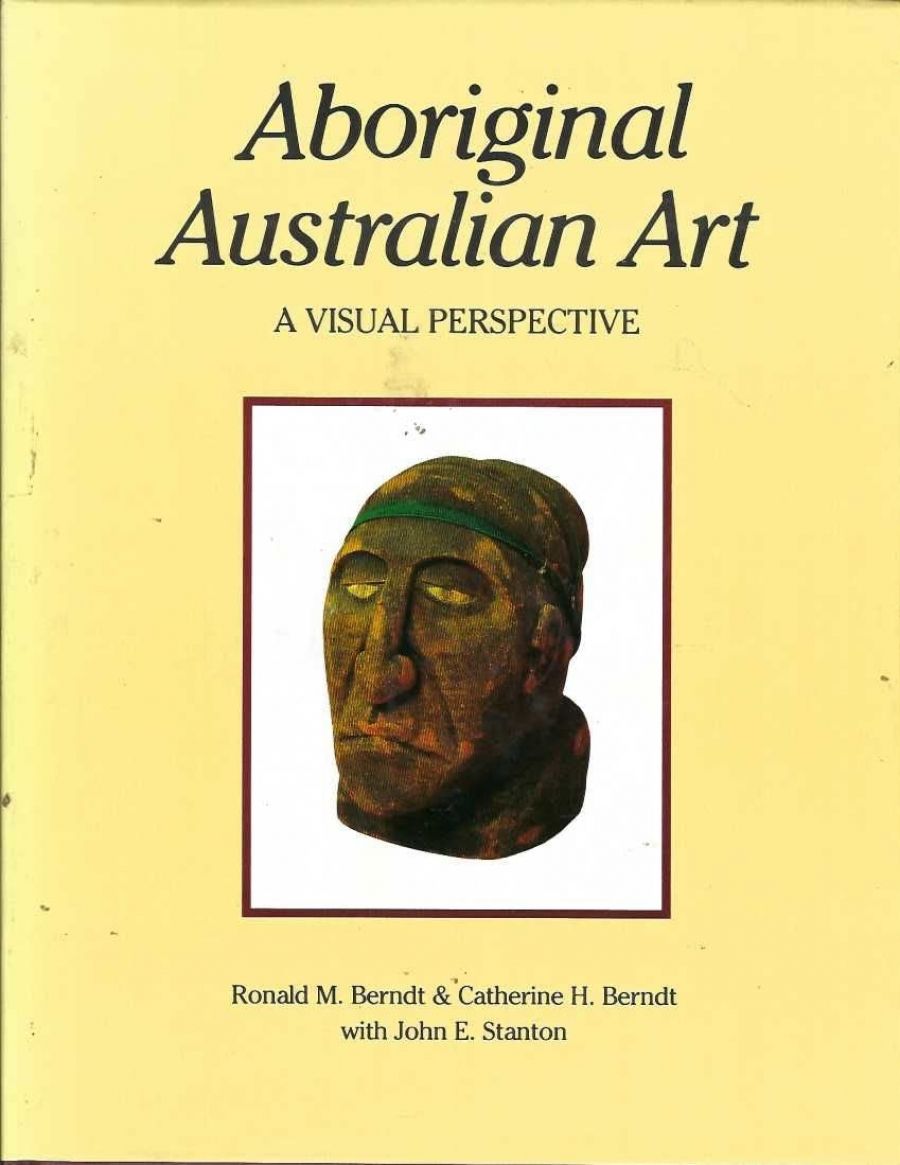

- Article Title: Rod Hagen reviews 'Aboriginal Australian Art: A visual perspective'

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: Despite the upsurge in the publication of books about Aboriginal life in recent years and the increased interest in traditional or ‘primitive’ art around the world, very few attempts have been made in this country to either reproduce substantial collections of photographs of Aboriginal art, or to provide serious, but readable. discussions of its relationship to the broader aspects of Australian society. This offering from the Berndts goes some way towards filling the gap between the coffee table glossies and the specialist publications of bodies such as the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Book 1 Title: Australian Art

- Book 1 Subtitle: A visual perspective

- Book 1 Biblio: Methuen, 176 pp, 153 colour plates

For the more serious student however there are some problems. Two things in particular worry me about the book. The first is of comparatively minor importance. All but ten of the 153 plates come from either the Northern Territory or Western Australia. While it is harder to obtain good material from the eastern states, it is certainly possible to obtain a much more balanced sample than the Berndts provide. Even the Northern Territory material is heavily biased towards material from Arnhem land. The superb works of the artists of Papunya and other central Australian communities warrant only three plates and the Arandic water colour specialists (Namatjirra et al.) are covered by a handful of early unrepresentative lumber crayon sketches.

The book does not provide the breadth of coverage that the title suggests. This selectivity is partly a reflection of the Berndts’ own areas of interest. They have relied very heavily upon their own collection as a source of material and this of course is primarily derived from the areas where they have carried out substantial fieldwork. It is also however partly due to a more serious flaw.

The Berndts’ approach to things Aboriginal is at times somewhat Rousseauian. Departures from the ‘purity’ of the pre- and early contact days are often seen by them as evidence of deterioration or cultural decay. This is not altogether surprising. Aboriginal society has, of course, been under massive attack from dominant white society for nearly two centuries. Many anthropologists. including the Berndts. have seen their role as one of preserving knowledge of a social system that they had good reason to believe was doomed to extinction. In such circumstances change and experimentation were seen as symptoms of the processes of destruction rather than as distinctive and interesting Aboriginal responses to new situations.

Thus, they suggest that each Aranda watercolour ‘stands on its own, can be understood immediately for what it is, and, unlike traditional Aboriginal art, requires no interpretation. It has, in fact, moved in a non-Aboriginal direction, virtually severing its traditional ties.’

What the Berndts are doing here is dramatically overemphasising the importance of form over the things that the artist is seeking to express. Notwithstanding the vast difference between these watercolours and ‘traditional’ Arandic art forms l have spent many fascinating hours discussing the ‘meaning’ of such paintings with these artists, very often in terms of the mythology of the area depicted (just as one can do with more ‘traditional’ forms of expression). At other times people have emphasised their own relationship to the place portrayed. Thus, although such paintings may be more accessible to Europeans as works that ‘require no interpretation’, to the artist concerned, and to other Aboriginal people, they possess quite different meanings. They are very much reflections of the world through Aboriginal, rather than European, eyes. The same can be said of Pitjantjatjara and Alyawarra Batiks, which receive very short shrift in the text and no pictures at all.

The early chapters of the book suffer a little from similar problems (although here the Berndts rest more heavily upon the shoulders of one of the founders of Australian Anthropology, Radcliffe Brown, than upon the visions of the Enlightenment). The outline that they provide of the relationship between Aboriginal people, land and art would be viewed by many anthropologists today as at times a little too simplistic. (Even, perhaps, dangerously simplistic at a time when the ‘realities’ of Aboriginal land tenure systems as seen by anthropologists can have important consequences for Aborigines in situations such as the hearings of the Aboriginal Land commission in the Northern Territory).

Nevertheless, these are very difficult areas to explore in a book intended for a general audience. Despite its limitations Aboriginal Australian Art has a great deal to offer the reader looking for an intelligent appreciation of Aboriginal Art in its traditional social context. It is certainly the best of its type to date.

Comments powered by CComment