- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

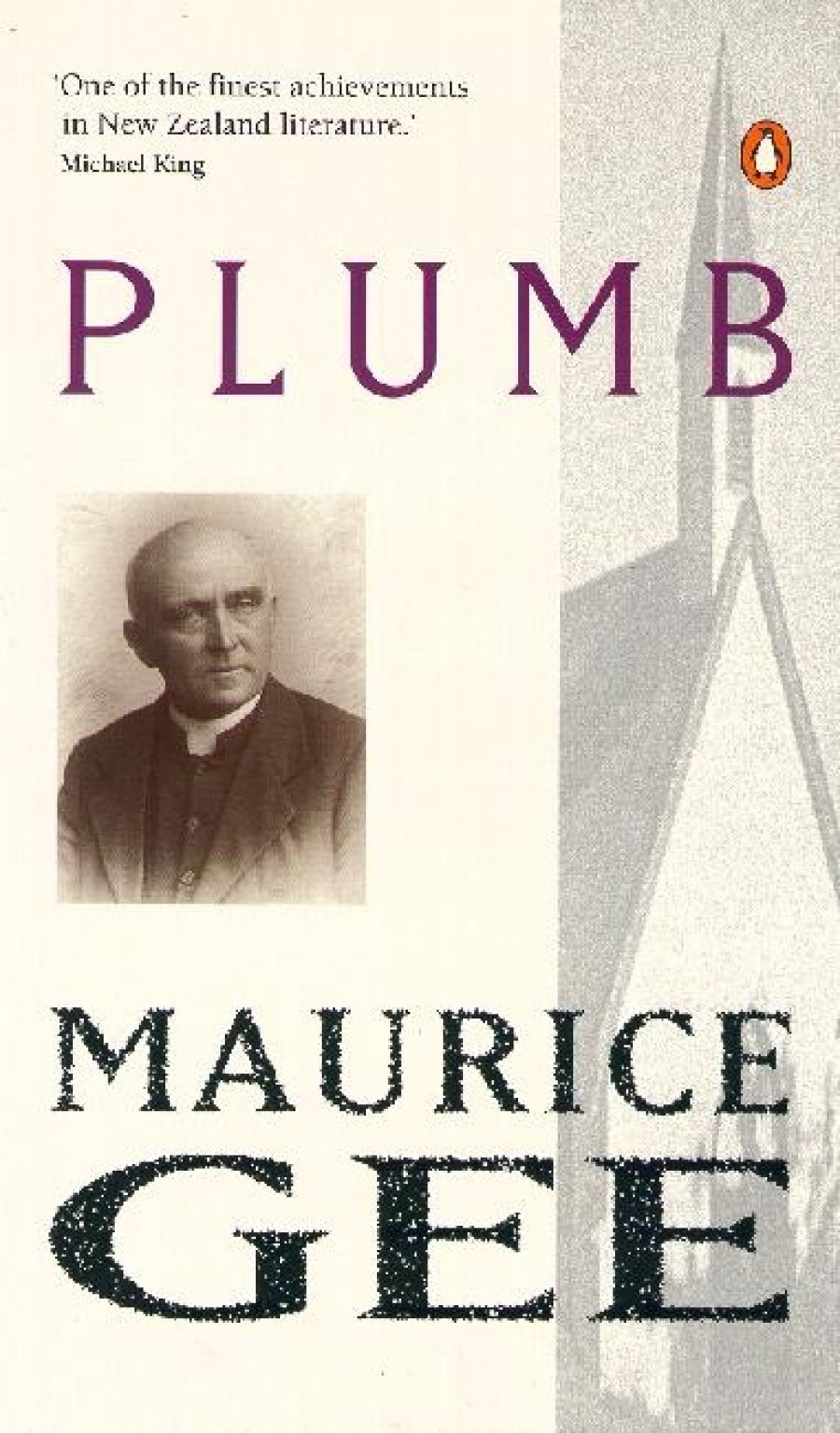

In a way, two words suffice for Plumb. Read it. It would be fair to add, ‘Make yourself read it.’ The inexorable, old man’s voice of its narrator George Plumb may irritate you, but before long you will respect his unrelenting and unsparing honesty with himself and his memories, and you will realise that everything he says has its place in this splendidly fashioned novel. At the end, he writes: ‘I thought, I’m ready to die, or live, or understand, or love, or whatever it is. I’m glad of the good I’ve done, and sorry about the bad.’

- Book 1 Title: Plumb

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus & Robertson, Sirius Quality Paperback Edition, 272 p.

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/kBZ7V

- Book 2 Title: Approaches

- Book 2 Biblio: Neptune Press, $6.95, $3.50, 137 p.

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_Meta/Sep_2020/META/approaches.jpg

Plumb is to find that because of his single-minded devotion to ideals his wife and family of twelve children suffered more than he had understood. To some of his children he seemed a quixotic and selfish parent, and a difficult husband to his wife who loved him and suffered in comparative silence. Of his twelve children one understands love so fully that he has power to ‘redeem’ his father during his journey – others are less forgiving, or enlightened.

All this is told in the most straightforward, unembellished language. Plumb is not a difficult book in the reading, but very dense and challenging as to its content. The style of a writer like Patrick White might seem poles apart from that of Maurice Gee, yet if Stan Parker were to tell his story in his own plain language, and deal with his own achievements, disappointments, marriage, and fatherhood as unsparingly as does Plumb, I think The Tree of Man and this novel would display interesting affinities.

The story of George and Edith Plumb to some extent parallels that of Gee’s grandparents, James and Florence Chapple. When you read the book you will realise why the name ‘Chapple’ was an accidental pun in the context of those lives, and why the name ‘Plumb’, whose many meanings are explored and exploited, is no cheap pun.

Plumb began life as an Anglican, changed to Presbyterianism in the 1890s and became a Presbyterian minister. He adopted the tenets of classical socialism and increasingly spoke publicly as a socialist until, inevitably, he was tried by and expelled from his church. Some years later he was imprisoned for his pacifist beliefs. Much of this mirrors Chapple’s life history. However, the twelve Plumb children are, Gee emphasises in a note at the end of the book, pure fictions and pure fiction is the domestic life of Edith and George Plumb. In the New Zealand quarterly Landfall, Number 17, March 1977, Gee published a fragment of Autobiography that is of particular interest about James Chapple.

The sectarian bitterness and political ferment which are central to the novel are wholly and excellently explained in fictional terms. One does not need to know much Australian or New Zealand history to comprehend the issues any more than one needs to be a student of the American Civil War to understand the background of Gone With the Wind.

Plumb has a great gallery of characters and a firm thematic line. Actual historical figures and occasions have their place in it. Recurring symbols contribute to the fugue-like qualities of the narration: eels and black water; trees and especially a quince tree; a handful of gold sovereigns. It is too dense to outline effectively or fairly in a short space, nor can I explain here why it is a tour de force of fictional architecture, but I am sure its structural qualities will have been an important factor in the award to it of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for the best novel published in Britain in 1978 as well as of two major New Zealand literary awards.

Visits of New Zealand authors to Australia, as writers in residence and to events like Writers Week at the Adelaide festival, help to make readers more aware of the excellent literature produced across the Tasman. But there is no substitute for actual books, and we do not see enough of them in shops here. Tourism makes introductions but ties of trade and sport seem stronger than cultural ones at present. This was not always so and I suspect the bonds we once had become loosened more or less by accident. It is very much time for re-weaving, and not only in literature, because some fine New Zealand painters and sculptors should be better-known here, too.

Therefore Angus & Robertson must be applauded for introducing Gee to Australian readers in the Sirius series – I hope he is a forerunner and that other New Zealand and Pacific region authors, Albert Wendt for example, may soon appear in Sirius books.

I talked of puns earlier and yield to temptation now: Garry Disher’s Approaches is a first book that makes a tentative approach to the excellence of Plumb. Its historical periods overlap and the questings of the young man, Peter, granted that they occur in a much later period, and range widely in the world, have affinities with the spiritual odyssey of the young George Plumb.

But Approaches is presented as a series of loosely related short stories each of which can be read singly (and indeed they have nearly all been published in literary magazines during the past four or five years). The best of the stories are very good indeed, but the book as a whole lacks structure and fairly early departs from its suggested homogeneity. No amount of frantic scrabbling at the end will put Peter or his life or his family together again.

Had Approaches been a bad book, I would have declined to write of it side by side with Plumb; that I do so is one measure of its inherent quality.

Frankly, I think Disher embarked on the wrong kind of building in the first place and used bonding cement too sparsely to hold his bricks together. Frank Moorhouse revived an old fashion under a new name when he spoke of his stories as being ‘a discontinuous narrative’ and tempted some.

Comments powered by CComment