- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Verna Coleman’s biography of Miles Franklin is extremely valuable but somewhat flawed. Those parts of Franklin’s life that are germane to the mateship tradition and the development of a nationalist Australian literature have been widely canvassed – although they take in only her precocious youth and mellow old age. The crucial decades between 1906 and 1927 are an almost total blank, even though they include the writing of her most important journalism and all but one of the novels on which her reputation rests. (Marjorie Barnard scarcely even tried to fill that blank with her 1967 biography.) Ms Coleman has restored those lost years and we must all thank her.

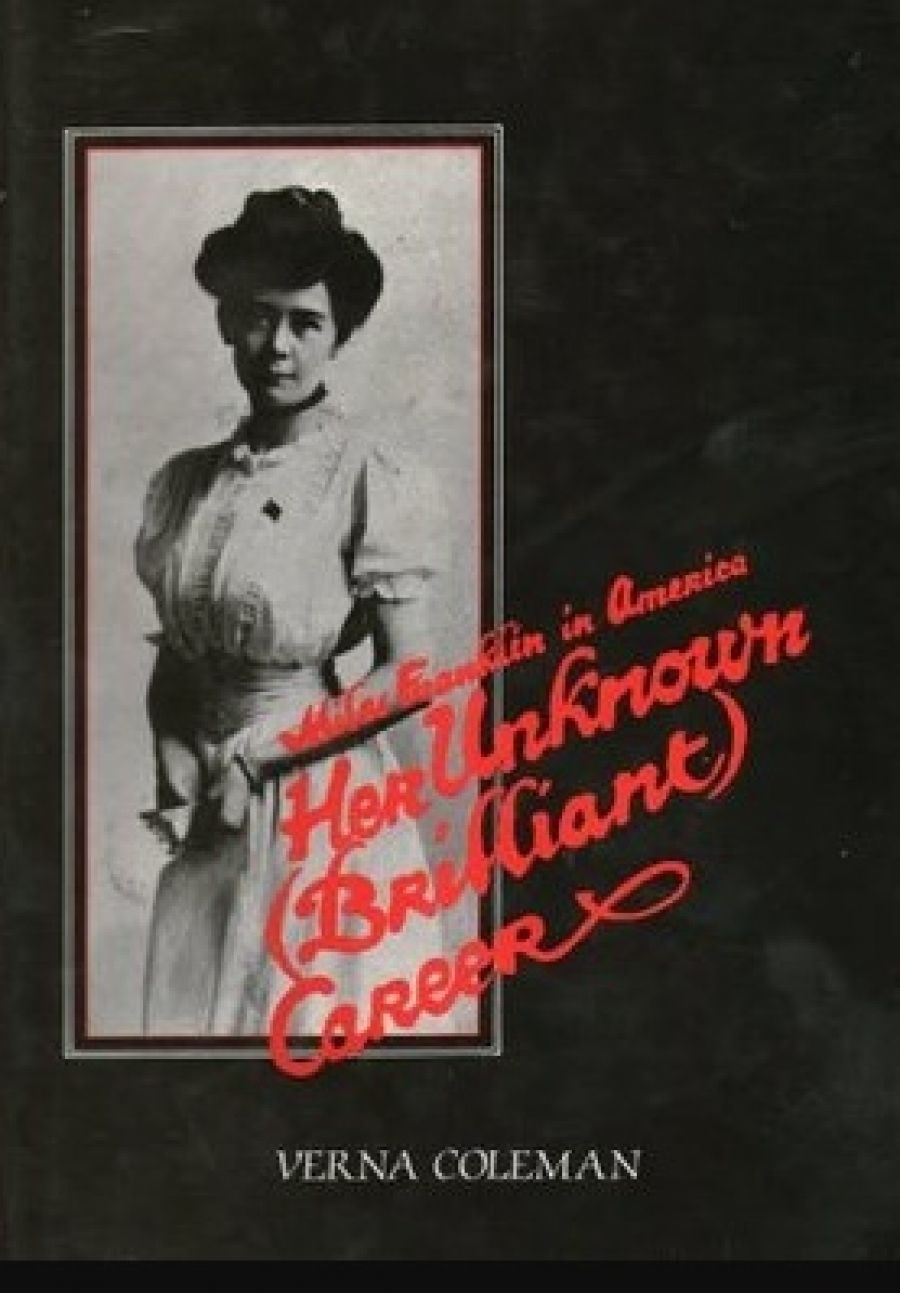

- Book 1 Title: Her Unknown (Brilliant) Career

- Book 1 Subtitle: Miles Franklin in America

- Book 1 Biblio: Sirius, Sydney, $15.95

Ms Coleman judiciously expands these slender notes with well-chosen extracts from Franklin’s writings, never making more claims for her inferences than the material will support. Miles Franklin in America corrects the facile view of Franklin as a writer first and feminist second, a view which can only be sustained by ignoring her prime of life. The book portrays the writer as a woman in conflict, not the ‘Merrily Miles’ beloved by most of her contemporaries. Furphy seems to be the only one of them who penetrated beyond her public face.

If Marjorie Barnard proved conclusively that Miles Franklin was also Brent of Bin Bin, Verna Coleman explains why she needed that protective imposture. The discovery that Franklin had problems will not surprise anyone but the facts that they were serious enough to be called ‘neurasthenia’ and that she overcame them so effectively in middle age should raise her in our esteem.

The book has two major weaknesses. The prose is workmanlike at best and, at worst, execrable. In addition, the analysis is occasionally superficial. Both flaws arise because the biographer is too fond of her subject – and perhaps too modest about her own skills.

There is a grammatical error or stylistic fault on every one of the book’s first hundred pages and a major chunk of rewriting needed for one chapter in two. These resemble Franklin’s own weaknesses so closely that I believe Ms Coleman’s prose was spoiled by osmosis: she has dipped too deeply into Franklin’s published work for her own good – and perhaps she did not trust her own taste enough to resist this influence. Perhaps, too, she concentrates too much on the foreground, which is dominated by Miles Franklin herself, and too little on the background. The historical background is adequate but the background in feminism and nationalism is sketchy.

In Exiles at Home, Drusilla Modjeska shows that nationalism was important to Miles Franklin and makes it clear that she shared the bigotry of her peers when the subject was race and empire as well as when it was sex. Franklin cannot be excused as merely holding ‘cranky ideas on population and eugenics’, even if we understand and share Ms Coleman’s affection for her.

Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own contains a pithy analysis of why women so often write badly. It is highly relevant to the weaknesses in Franklin’s non-journalistic works. Novelists, poets, and playwrights, says Woolf, must be free of personal angers, anxieties, and axes to grind. Franklin did not achieve that freedom until she was almost fifty, when she began writing as Brent of Bin Bin from Seat S9 in the British Museum. Even so, her pen snagged the page when she discussed sex, marriage, and mores

I am not saying that Franklin was a neurotic virgin. Coleman shows fairly conclusively that her wedding ring, which so fascinated Marjorie Barnard, was not worn as a symbol of marriage. Who knows if it was a symbol of respectability, worn when she stayed at discreet hotels with married men? Franklin had little sympathy for sex or motherhood and no pressing financial or psychological need for marriage. She remained, however, a Victorian about sex until her death in 1954. An apple does not fall far from its tree and Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin came from generations of dominating, puritanical women.

Coleman has done something more important than establishing that Franklin almost certainly remained a spinster, perhaps even a virgin: she demonstrates that the great, tormenting, warping conflict in Franklin’s life was not the choice between marriage and spinsterhood but between political activism and creative writing. This conflict was at least resolved in her best novels, although she was never entirely free of it.

Her Unknown (Brilliant) Career is not a classic of biographical style any more than Her Brilliant Career is a classic of juvenile writing. However, Verna Coleman certainly has the capacity to become a classic biographer and I hope I have the privilege of reviewing her next book.

Comments powered by CComment